Of the six children of Levi Rothschild and Clara Jacob who lived to adulthood in Germany, amazingly all but one escaped from Germany in time to avoid being killed by the Nazis. Only the youngest sibling Frieda was not as fortunate. But that doesn’t mean that there wasn’t suffering and loss endured by the other five. This post will focus on the three oldest children: Sigmund, Betti, and Moses.

Sigmund Rothschild and his wife Fanny Rosenbaum escaped to South Africa. I don’t know when or how they immigrated there, but Fanny died there on August 20, 1942, in Capetown at the age of 62.

Fanny Rosenbaum Rothschild death record, Municipality or Municipality Range: Cape Town

Ancestry.com. Cape Province, South Africa, Civil Deaths, 1895-1972

Her husband Sigmund died in Capetown three years later on December 23, 1945; he was 71.

Sigmund Rothschild death record, Municipality or Municipality Range: Cape Town

Ancestry.com. Cape Province, South Africa, Civil Deaths, 1895-1972

As for Sigmund and Fanny’s son Kurt, I have very little information. An entry in the England & Wales Civil Registration Death Index on Ancestry shows that he died in Lancaster, England, and that the death was registered in September 1997.1 A FindAGrave entry shows his gravestone with the date of death as August 30, 1997.

Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/81923216/kurt-rothschild: accessed April 19, 2024), memorial page for Kurt Rothschild (1910–3 Sep 1997), Find a Grave Memorial ID 81923216, citing Lytham Park Cemetery and Crematorium, Lytham Saint Annes, Fylde Borough, Lancashire, England; Maintained by ProgBase (contributor 47278889).

The Ancestry tree that appears to have been created by Kurt’s daughter-in-law shows that Kurt married Erna Erdmann and had one child, who is the home person on that tree. I have not been able to find a marriage record for Kurt and Erna Erdmann or a birth record for their child, so I am hoping that the owner of that tree will respond to the message I sent to help me find out what happened to Kurt Rothschild and his family. But since it’s been well over two months at this point, I am not optimistic that I will hear from her anytime soon.

The second child of Levi and Klara, their daughter Betti, lost her husband Emanuel Hirschmann on November 4, 1932. He died in Fulda, Germany, and was 64.

Emanuel Hirschmann death record, Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Wiesbaden, Deutschland; Personenstandsregister Sterberegister; Signatur: 2470, Year Range: 1932, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Deaths, 1851-1958

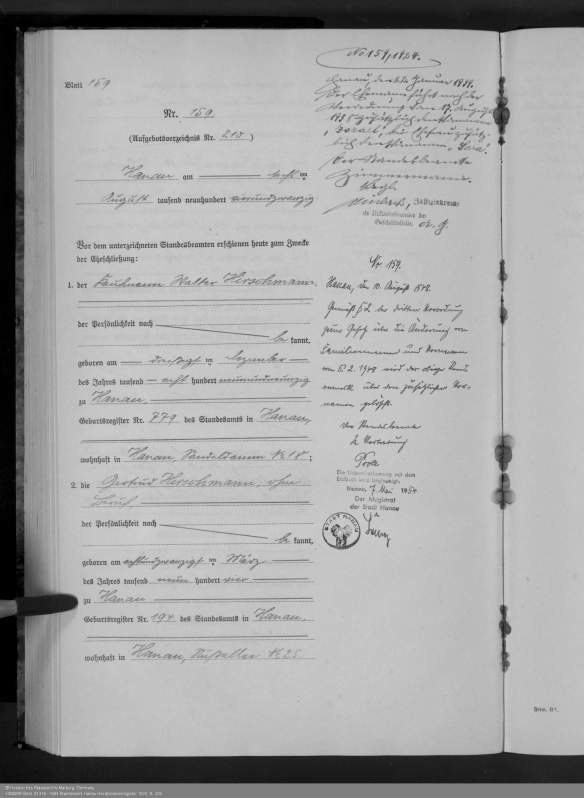

Their son Walter had married Gertrud Hirschmann on August 6, 1924, in Hanau, Germany. Gertrud was born in Hanau on March 28, 1904, according to their marriage record, but that record does not include her parents’ names. It would appear that Gertrud was likely a relative given the surname and her birth place, but so far I’ve not found any way to connect her to Walter’s Hirschmann relatives.

Walter Hirschmann and Gertrude Hirschmann marriage record, LAGIS Hessen Archives, Standesamt Hanau Heiratsnebenregister 1924 (HStAMR Best. 913 Nr. 1894)AutorHessisches Staatsarchiv MarburgErscheinungsortHanauErscheinungsjahr1924, p. 328

Walter and Gertrud and their twelve year old daughter immigrated to the US on a December 15, 1938. Walter listed his occupation as a banker and their last residence as Frankfurt, Germany, where his mother “B. Hirschmann” was still residing. They were heading to a friend, L. Schwarzchild, in New York.2

Walter’s mother Betti Rothschild Hirschmann immigrated to the US on March 25, 1939, with a cousin of her husband, Emil Hirschmann, and his wife Paula.

Betti Rothschild passenger manifest, The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957; Microfilm Serial or NAID: T715; RG Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; RG: 85, Ship or Roll Number: Veendam, Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957

On the 1940 census, Betti was living as a lodger in the household of Helena Pessel in New York City, but in the same building as her son Walter and his family at 670 Riverside Drive in New York City. Walter was employed as a salesman.3

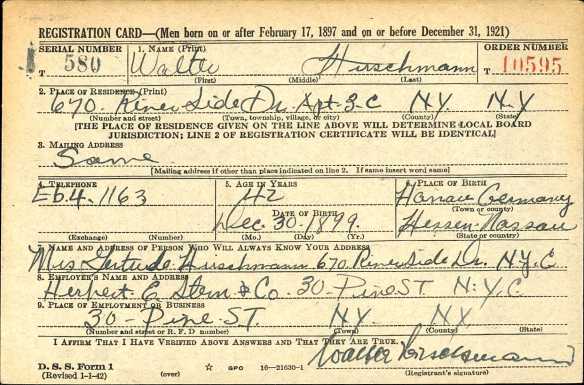

On his World War II draft registration, Walter identified his employer as Herbert E. Stern & Company. From his obituary I learned that Herbert E. Stern was also a refugee from Nazi Germany and an investment banker.4

Walter Hirschmann World War II draft registration, National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; Wwii Draft Registration Cards For New York City, 10/16/1940 – 03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147, Name Range: Hirsch, Walfgang-Hobbs, Robert, Ancestry.com. U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947

In 1950 Betti was still living in the same building as her son Walter and his family. Walter was still working as a broker and banker. I am very grateful to Eric Ald of Tracing the Tribe who found the 1950 census record for Betti and also a listing on Ancestry in the New York, New York Death Index for a Betty Hirschmann who died on February 15, 1956.5

Walter Hirschmann and Betty Hirschmann, 1950 US census, National Archives at Washington, DC; Washington, D.C.; Seventeenth Census of the United States, 1950; Year: 1950; Census Place: New York, New York, New York; Roll: 6203; Page: 75; Enumeration District: 31-1900, Ancestry.com. 1950 United States Federal Census

Her son Walter Hirschmann died on June 24, 1977, at the age of 77.6 He had been predeceased by his wife Gertrud, who died in December 1966 7 and was survived by their daughter and grandchildren.

Sigmund and Betti’s brother Moses/Moritz Rothschild and his wife Margarete David ended up in Israel/Palestine in the 1930s along with their two children, Ruth, born October 8, 1914, in Magdeburg, Germany, and Herbert (later Yehuda), born December 10, 1921, in Magdeburg. The documents below are immigration documents showing that Moritz and Margarete were in Jerusalem by June 30, 1939; these and the others that follow were found at the Israel Genealogy Research Association website.

Registration form for Margarete David Rothschild reporting to the German Embassy Legation at the German Consulate General Consulate Bizekonsult in Jerusalem, A-B (טפסי הרשמה: A-B), part of the Residents 1938-1939 (תושבים 1938-1939) database, system number פ-500/5, IGRA number 1459. The original records are from Israel State Archives (ארכיון המדינה), and found at the IGRA website.

Registration form for Margarete David Rothschild reporting to the German Embassy Legation at the German Consulate General Consulate Bizekonsult in Jerusalem, A-B (טפסי הרשמה: A-B), part of the Residents 1938-1939 (תושבים 1938-1939) database, system number פ-500/5, IGRA number 1459. The original records are from Israel State Archives (ארכיון המדינה), and found at the IGRA website.

Registration form for Moses Moritz Rothschild, This record comes from the Meldeblaetter: A-B (טפסי הרשמה: A-B), part of the Residents 1938-1939 (תושבים 1938-1939) database, system number פ-500/5, IGRA number 1462. The original records are from Israel State Archives (ארכיון המדינה), and found at the IGRA website.

Registration form for Moses Moritz Rothschild, This record comes from the Meldeblaetter: A-B (טפסי הרשמה: A-B), part of the Residents 1938-1939 (תושבים 1938-1939) database, system number פ-500/5, IGRA number 1462. The original records are from Israel State Archives (ארכיון המדינה), and found at the IGRA website.

Their daughter Ruth had arrived by September 29, 1938.

Registration form for Ruth Rothschild reporting to the German Embassy Legation at the German Consulate General Consulate Bizekonsult in Jerusalem, A-B (טפסי הרשמה: A-B), part of the Residents 1938-1939 (תושבים 1938-1939) database, system number פ-500/5, IGRA number 1465. The original records are from Israel State Archives (ארכיון המדינה), as found at the IGRA website.

Registration form for Ruth Rothschild reporting to the German Embassy Legation at the German Consulate General Consulate Bizekonsult in Jerusalem, A-B (טפסי הרשמה: A-B), part of the Residents 1938-1939 (תושבים 1938-1939) database, system number פ-500/5, IGRA number 1465. The original records are from Israel State Archives (ארכיון המדינה), as found at the IGRA website.

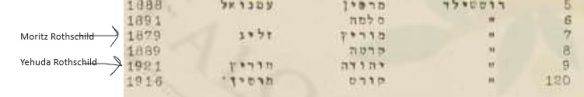

Although I was unable to find a comparable record for Herbert/Yehuda, I found a record showing that he and his father Moritz were on the voter registration list and living at Kfar Yedidya in 1942:

Moritz and Yehuda Rothschild on 1942 Knesset register, This record comes from the Voters List Knesset Israel 1942 (פנקס הבוגרים של כנסת ישראל תש”ב), part of the Voters Knesset Israel 1942 (בוגרים של כנסת ישראל 1942) database, system number 001mush, document number 119, line 59, IGRA number 1107. The original records are from Israel State Archives (ארכיון המדינה), and was found at the IGRA website.

Yehuda married Ruth Hesin, daughter of Avraham and Hava, on April 17, 1949, in Haifa, Israel. She was 22 years old, he was 27.

Yehuda Rothschild marriage record, Marriage/Divorce Certificates (תעודות נישואין / גירושין), part of the Marriages and Divorces 1921-1948 Palestine British (נישואין וגירושין 1948-1921 ארץ ישראל) database, document number 91714, IGRA number 507. The original records are from Israel State Archives (ארכיון המדינה), and was found at the IGRA website.

At this time I have no further records for this family, but we know that at least they escaped from Germany in time to survive the Holocaust.

Thus, the first three children of Levi Rothschild and Clara Jacob all escaped from Nazi Germany in time, but look at what they lost. They were all spread across the globe: Sigmund in South Africa, Betti in the United States, and Moses in Palestine/Israel.

The fourth child of Levi and Klara, their son Hirsch Rothschild, also escaped. He and his wife Mathilde Rosenbaum and their three children Gertrude, Edith, and Edmund ended up, like Betti, in the US. I will write about Hirsch and his family in my next post.

- Kurt Rothschild, Death Age 87, Birth Date 30 Mar 1910, Registration Date Sep 1997, Registration district Lancaster, Inferred County Lancashire, Register Number A58B, District and Subdistrict 5871A, Entry Number 166, General Register Office; United Kingdom, Ancestry.com. England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1916-2007 ↩

- Walter Hirschmann and family, passenger manifest, The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957; Microfilm Serial or NAID: T715; RG Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; RG: 85, Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957 ↩

- Betti Hirschmann, 1940 US census, Year: 1940; Census Place: New York, New York, New York; Roll: m-t0627-02671; Page: 7B; Enumeration District: 31-1929, Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census. Walter Hirschmann and family, 1940 US census, Year: 1940; Census Place: New York, New York, New York; Roll: m-t0627-02671; Page: 7A; Enumeration District: 31-1929, Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census ↩

- “Herbert E. Stern Dead, An Investment Banker,” The New York Times, August 6, 1973, p. 32. ↩

-

Betty Hirschmann, Age 75, Birth Date abt 1881, Death Date 15 Feb 1956, Death Place Manhattan, New York, New York, USA, Certificate Number 3638, Ancestry.com. New York, New York, U.S., Death Index, 1949-1965. Although there is a listing for Betti on the SSCAI with her Social Security Number, there is no listing on the SSDI for her under that number or under that date or under her name. Betty Sara Hirschmann, [Betty Sara Rohserild], Gender Female, Race White, Birth Date 14 Sep 1876, Birth Place Borken Hesse, Federal Republic of Germany, Father Levi Rohserild

Mother, Clara Jacob, SSN 057200860, Notes Feb 1943: Name listed as BETTY SARA HIRSCHMANN, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007. ↩ -

Walter Hirschmann death notice, The New York Times, June 27, 1977, p, 30. Walter Hirschmann, Social Security Number 092-14-5701, Birth Date 30 Dec 1899

Issue year Before 1951, Issue State New York, Last Residence 10023, New York, New York, New York, USA, Death Date Jun 1977 Social Security Administration; Washington D.C., USA; Social Security Death Index, Master File, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014 ↩ - Gertrud Hirschmann death notice, The New York Times, December 16, 1966, p. 47. ↩