Although leaving Poland was hard, arriving in Budapest was delightful. We weren’t even ripped off by the cabbie this time. We arrived at our hotel at 9 am after another overnight train, and when we walked into our hotel, the Boscolo, we were a bit in awe. We’ve never been in a hotel as beautiful as the Boscolo. The atrium in the lobby is glamorous and gorgeous. It may be a bit ornate for our usual taste, but there was no denying the way that large, well-lit, and finely decorated space made us feel. After a breakfast in their famous New York café, we were able to get an early check-in to our room, which also stopped us in our tracks—-a very large and well-appointed room with a little balcony. It felt like we were in some fantasy world.

Although it would have been tempting just to enjoy our surroundings, we had things to see and do. Although the concierge at the hotel warned us that our destinations would require a long walk, we were not intimidated. And as it turned out, although we walked quite a bit, we did not regret it. We love walking in cities (and beaches and just about anywhere); only by walking do you get a feel for the scale of a city and its buildings and only by walking do you make eye to eye contact with the people around you. So we ventured out for our first day in Budapest.

First, we went to the House of Terror, a museum that primarily tells the story of what life was like in Budapest under Soviet domination. The museum is in the building which the Soviets used as their headquarters and where they also imprisoned, interrogated, and tortured prisoners. The cells and the instruments of torture are still there. It is a powerful museum; the use of symbols is particularly effective. We were very moved by our experience there.

Our next stop was the Budapest Opera House, where we had tickets for a tour and a mini-concert. The opera house was impressive and uplifting, especially after the darkness of the House of Terror. The gold and red colors which ran throughout the building gave it a truly regal feeling. And the mini-concert was fun—one opera singer came out and performed two arias for us. (Don’t ask me what they were—-I am not really an opera fan.)

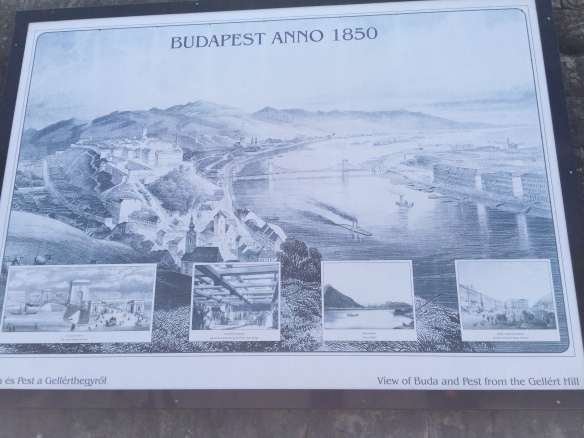

We headed to our final stop for the afternoon, the Parliament, where we also had tickets for a tour. The Parliament is huge—I don’t think I’ve ever seen such a large building. It sits right on the Danube River, extending fairly far along its shore, and there is a huge open plaza surrounding the building. We strolled around, looking at the not-at-all blue Danube and across the river to Buda and then entered the building in time for our tour.

The security to enter the building was more intense than what we had gone through at any airport, which was a bit unnerving. But once we were in, the guide led our group through the building, which was originally intended to be finished for the 1896 Millennial Celebration, but was not finished in time. Hungarians believe that the Magyars arrived from Asia to the Carpathian plains where Hungary is located around 895, but because plans for the millennial could not be completed in time for 1895, they postponed it a year and claim now that the country was founded in 896. Like so many countries in Central Europe, Hungary was subjected to many invasions and wars over the year, eventually becoming part of the Austria-Hungary Empire as the result of a compromise with the Habsburgs in 1867. The Parliament building was originally meant to be the Habsburg’s palace, but after World War I and the end of the Austria-Hungary Empire, it became the home of the Hungarian Parliament.

Like the Opera House and the hotel and many of the other buildings we would see in Budapest, it is an ornate and beautiful building, conveying a sense of prosperity and power. The crown jewels sit in a case under a large dome (we were not allowed to photograph them), evidence of the royalty who once ruled the land. We also saw the chambers of the Parliament, equipped with modern digital voting machines at each desk—a strange mix of the old and the new. It was a very interesting tour and gave us a quick overview of Hungarian history.

By that time we were a bit tired and hungry and ready to find a place to eat. We strolled along the river watching the Viking Cruise and other companies’ “river boats,” then turned to walk through the center of the city, where we happened upon a restaurant called Rezkaka. The menu looked creative, and the atmosphere seemed relaxing, so we took a chance. It was our best meal of the trip. The violin and piano playing in the background didn’t hurt either.

As we left the restaurant, the night sky was getting dark (it was about 9 pm), the ferris wheel in the city center was lit up as were many of the buildings. It was magical. We decided to keep on walking (despite what the concierge had said), and we passed the Dohany Synagogue, all lit up. We were using the GPS on my iPhone to guide us back to the hotel, and it led us through the Jewish quarter, which has become a hip place, filled with “ruin bars” patronized by 20-somethings. It was an entertaining walk back, and by the time we reached the hotel, we were quite proud of ourselves for the distance we had walked and quite enamored with Budapest.

Our next day started with a tram ride (we decided to give our feet a little break) to the Central Market in Budapest—an amazing place filled with fresh fruit, vegetables, meat of all kinds, paprika, and flowers. And it’s a real market—not a tourist joint. We could see regular people with shopping bags and carts, buying their groceries.

From there we walked somewhat aimlessly through several streets and squares, passing the university buildings, a street of touristy shops, a street of high fashion designer shops, and the second McDonalds to open behind the Iron Curtain.

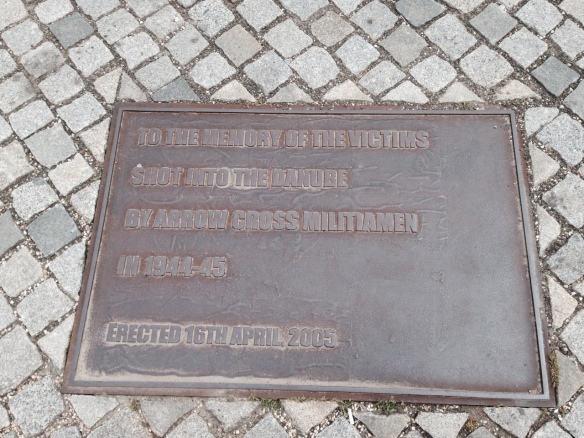

We were aiming for the Holocaust Memorial on the river. During the Holocaust, Jews were rounded up and brought to the river, where three people would remove their shoes, be tied together, and one would be shot, forcing all three to fall into the river and die. The memorial captures this atrocity very simply and poignantly with sculptures of many pairs of empty shoes, lining the wall that abuts the river.

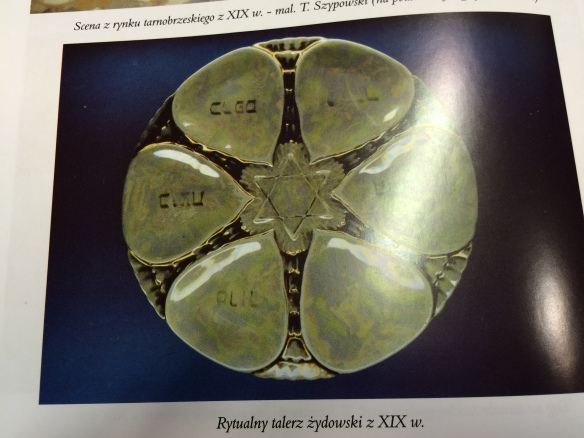

For the afternoon we had signed up for a tour of the Budapest Jewish Quarter with Budapest Jewish Heritage Tours. It was supposed to be a group tour, but luckily for us, no one else had signed up at that time, so we ended up with a private tour. We actually had three guides. Ann, our first guide, gave us a general introduction; she then brought us to the Jewish Museum, which is right next to the Dohany synagogue. At the museum we were guided by Esther, who works for the museum. After we finished at the museum, Fatima met us to take us to see the synagogues in the quarter. Each guide was knowledgeable and personable, and we learned a great deal about the history of Budapest’s Jewish community.

There were Jews in Budapest from as early as Roman times, though not a permanent settlement. As in the other countries in Central Europe we visited, Jews came to Hungary as traders and bankers. They faced a great deal of violence and anti-Semitism, and for a long time were required to live on the Buda side of the river while working on the Pest side. Eventually they were allowed to live on the Pest side, but outside the city walls. The area where they settled in the 18th century became the Jewish Quarter where even today there are numerous active synagogues, kosher restaurants, and other Jewish institutions. The community flourished in the 19th century, and by the 1930s there were over 200,000 Jews in Budapest.

Perhaps the best indication of the size and prosperity of the Jewish community in Budapest is the Dohany Synagogue, the second largest synagogue in the world and a magnificent structure built in the middle of the 19th century. It was built for a congregation that wanted to be more modern in its practice of Judaism. They called themselves Neologs (new law). Although men and women were still separated for services, there was an organ (played by Franz Liszt at the inauguration of the building), and the interior was designed to be more church-like than like a traditional synagogue. Like the Spanish Synagogue in Prague, the design reflects a Moorish influence both inside and out.

Our guides pointed out, however, that Hungary had a long history of anti-Semitism, and in the 1920s a law was passed establishing quotas at the universities. In the 1930s. Hungary adopted laws stripping Jews of their rights even before the Nazis began their occupation of the country. Although Hungarian Jews were among the last to be deported to concentration camps, our guide in Poland, Tomasz, had explained that that was simply because the Hungarians wanted to exploit the Jews for free labor, not because they were trying to protect them. In the end, most of Hungary’s 600,000 Jews were killed, 400,000 of them at Auschwitz on some of the last transports to arrive there.

The Dohany Synagogue survived the war because it was used by the Nazis both for storage and as a place for radio towers since it had the two high spires on its roof. Behind the Dohany Synagogue is a memorial garden dedicated to those who were killed in the Holocaust. I found the sculpture of the Tree of Life that resembles an upside down menorah particularly moving.

We saw two other synagogues after leaving the Dohany. First we visited the Orthodox synagogue, built in 1912, another very beautiful building, and then we saw the Rumbach Street synagogue. From what Vatima told us, this last synagogue was formed by a group that spit off from the Neologs; they felt the Neologs had moved too far away from traditional Judaism, but they also did not agree with the strict practice of the Orthodox synagogue. This building was under renovation and not open to visitors, so we only got to see its exterior, which was quite beautiful.

Overall, our experience in the Jewish Quarter in Budapest was much more uplifting than in either Prague or Krakow in large part because we learned that there is still a very substantial and active Jewish community in Budapest, consisting of about 80,000 people. Although that is less than half of the Jewish population of Budapest in 1939, it is nevertheless a promising sign of rebirth and hope for the future.

Our day in Budapest ended with a quick dinner and an organ concert at St. Stephen’s Basilica, the largest church in Budapest—and yet again, a magnificent building.

For our third and last day in Budapest, we had arranged for a driving tour to see those sites that really are too far for walking, even for us. Our guide Magdi took us out to Heroes Square and through the City Park, two more spaces that were developed specifically for the Millennial Celebration in 1896. We saw Hungarian soldiers practicing for a parade while we were there.

Legend says if you touch this guy’s pen, your writing will be successful. FIgured it was worth a try….

Then we crossed the Danube to Buda where the Castle is—where once again we learned that almost everything there was either built or redone for the Millennial Celebration. What impressed us most were the incredible panoramic views we could see from the Fishermen’s Bastion and from the Castle itself. Magdi did point out some older buildings in Buda that dated back to earlier times, but overall most of what we saw dated from 1896 or so. The glaring (literally and figuratively) exception was the Hilton, a modern building of reflective glass that just does not fit into the setting.

Finally we went to Gellert Hill, where we were able to view Budapest from yet another perspective and see the fortress built there.

Our tour ended by dropping us off at the Gellert Spa and Baths. Everyone had told us that we had to try the baths while in Budapest, and so we did. It was an interesting experience—soaking in a hot pool with a bunch of elderly Hungarian women who did not really look so pleased to have us invading their space. But we were glad we tried it, and that hot water was very relaxing. After all the walking we had done in our three days in Budapest, our feet certainly deserved the break!

Looking back on our time in Budapest, I would say it was the city where we had the most light-hearted moments in our trip. Maybe we just needed to focus more on the beauty, less on the tragic, after seeing Terezin, Krakow, and Auschwitz. Maybe it was the Hungarian people or the energy of the city, where the streets were crowded with young people at night. Maybe it was all the beautiful buildings and breath-taking views and sights we saw. For whatever reason, we left Budapest the next morning feeling uplifted.

Our trip was almost over. We had a train ride to Vienna and a day and a half in that city before returning home. And home was starting to sound like a good place to be.

![Wenceslas Square By Peter Stehlik - PS-2507 (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/wencselas-square.jpg?w=584&h=390)