About a month ago, my father (who reads the blog regularly) asked me when I was going to get to his grandparents. Although I wanted to get there also, my linear mind would not let me “skip ahead.” I knew that if I did, I’d get too caught up in my direct ancestors and not want to return to all the “lateral” relatives. So I have stuck, more or less, to my plan and taken each of Jacob and Sarah’s children in birth order. (Yes, I had to skip Reuben and Arthur while waiting to hear from descendants, but otherwise, I went in order.) There are still two more children to do after my great-grandfather, Jonas and Abraham, so I still have to resist the temptation to move on to my great-grandmother’s Seligman line. Also, I still have to return to Jacob’s brother Moses and his family and also some of Jacob and Sarah’s grandchildren whom I’ve yet to research or discuss.

But for now, I finally get to talk about my father’s grandfather Emanuel and his family. Sadly, my father never knew Emanuel because he died just a few months after my father was born. There is no one else left for me to ask about Emanuel since there are no other descendants still alive who would remember him. But my father knew his grandmother, Emanuel’s wife Eva May Seligman, very well, and he remembers other family members as well, although he has not seen or been in touch with them for more than 60 years. And I never knew any of his Cohen relatives other than my aunt, Eva H. Cohen, who died in 2011. I never met my father’s father or his uncles or his cousins.

Thus, most of what I know about Emanuel and his sons and their families is based on the same kind of resources I’ve relied upon in all my other research, sprinkled with some family stories from my father or indirectly from my aunt as my brother remembers them. As I was writing this post, my father also sent me copies of pages from a family bible that revealed some other dates of births, marriages, and deaths. There is also a suitcase filled with photographs and papers in my parents’ garage that I have not yet had a chance to examine. I hope to get to that suitcase soon, but it may have to wait until after the summer.

That means that right now I have no pictures of my Cohen great-grandparents and only a few of my grandfather. I have none of his brothers or their children. Of course, it is in part because of this lack of knowledge that I started doing this work in the first place. I knew so little about any of my grandparents, less about my great-grandparents, and nothing about my great-great-grandparents. Now I am working hard to fill in those gaps.

So let me start to tell the story of my great-grandparents Emanuel and Eva Seligman Cohen, and eventually I will have to come back and add some pictures and other materials, assuming some exist in that suitcase.

My great-grandfather Emanuel was the eleventh child of Jacob and Sarah Cohen, born June 10, 1862, during the Civil War. (The family bible has a different date—June 14, 1860, but given that I have eight other sources indicating he was born in 1862, including his death certificate, I will stick with the 1862 date.) In 1870, when he was eight years old, he was living with his parents and ten of his twelve siblings at 136 South Street in Philadelphia. I imagine that his childhood was a happy one. His father’s business was successful, and he was surrounded by siblings. His oldest sister Fanny was married when Emanuel was only four, and he had nieces who were only a little older than he was in addition to all his siblings. His brother Lewis was only two years older and his brother Jonas two years younger. It must have been quite a household.

Jacob Cohen and family 1870 US census

By 1880, his life had changed. His mother Sarah had died in 1879, and only five of his siblings were still living at home: two of his older sisters, Hannah and Elizabeth, and his three brothers closest to him in age, Lewis, Jonas, and Abraham. Emanuel was working as a clerk in one of the pawnshops. He was eighteen years old.

Jacob Cohen and family 1880 US census

On January 27, 1886, Emanuel married my great-grandmother, Evalyn Seligman, who was later known as Eva May and as Bebe by her grandchildren after my aunt called her that when she was a toddler. I don’t know how my great-grandparents met. He was 24, she was 20. In 1886, they were living at 404 South Second Street, and Emanuel was working for his father’s pawnbroker business. Their first child, Herbert S. Cohen, was born on either January 28 (family bible) or March 5, 1887 (Philadelphia birth index). On this one, I will rely on the bible as the entry was made by Herbert’s mother, Eva May, who would best know when her child was born. Their second child, Maurice Lester Cohen, was born on February 27, 1888 (both sources agree here), and the family was living at 1313 North 8th Street, and Emanuel was working at 901 South 4th Street.

On October 17 (bible) or 22, 1889, two and a half year old Herbert died from typhoid fever, as had several of his little cousins. Just two weeks later, a third son, Stanley Isaac, was born on November 4, 1989. How terrible it must have been for my great-grandparents to be mourning one child while another was born. How did they find a way to celebrate that birth and manage through those difficult, early weeks of infancy while their hearts were broken?

Herbert Cohen death certificate 1889

In 1890, the family was still living at 1313 North 8th Street, and Emanuel was still working as a pawnbroker at 901 South 4th Street. They were still there in 1893 because when Emanuel’s uncle, Jonas H. Cohen, died in January, 1893, the funeral took place at Emanuel and Eva May’s residence. I wonder why, of all the nephews and nieces of Jonas, Emanuel was the one to have the funeral at his home.

(“Mortuary Notice,” Thursday, January 26, 1893, Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA) Volume: 128 Issue: 26 Page: 6)

By 1895, the family had moved. Emanuel’s brother Isaac had also lost his wife Emma in 1893, and as of 1895, Emanuel and his family had moved into Isaac’s house at 1606 Diamond Street, presumably to help Isaac take care of his teenage son, Isaac W. On December 6, 1895, my grandfather, John Nusbaum Cohen, was born, completing Emanuel and Eva’s family. Emanuel continued to work at the 901 South 4th Street pawnshop.

John Nusbaum Cohen about 1896

As I wrote about previously, Isaac was sixteen years older than Emanuel, so I am not sure why, of all the siblings, he chose to live with his much younger brother Emanuel. I think it says a lot about what kind of people Emanuel and Eva May were, taking in these two family members while also raising three boys of their own. Emanuel and Eva had also been the ones who opened their home for the funeral for Emanuel’s uncle Jonas. According to the 1900 census, they did, however, also have two servants helping them in the home so perhaps it was not as onerous as it might seem; perhaps they were the best situated to do these things.

Emanuel Cohen and family 1900 census

I would imagine that the 1890s were overall not an easy decade for the extended Cohen family. First, the family patriarch, Jacob, died on April 24, 1888, just two months after Maurice was born. His brother Jonas H. Cohen, the last of Hart and Rachel’s children, died five years later on 1893. Also, a number of Jacob’s young grandchildren died during this decade, including many of Reuben and Sallie’s children and also Benjamin Levy, Maria’s son. His brother Isaac had lost his wife Emma. On the other hand, there were many children born, many siblings married, and business overall seemed to be thriving for the family pawnshops.

As of 1905, Emanuel and his family had moved down the street to 1441 Diamond Street. On the 1910 census, they are listed as living at 1431 Diamond Street, and Isaac, Emanuel’s brother, was still part of the household, along with Eva, all three of Emanuel’s sons, and two servants. Maurice, who was 22, was working as a salesman for a clothing business; Stanley (20) and John (14) were not employed outside the home.

Emanuel Cohen and family 1910 census

In the 1913 and 1914 city directories Emanuel is listed as a pawnbroker at 1800 South 15th Street. His brother Isaac died in 1914, and as of 1917 the family had moved again, this time to 2116 Green Street.

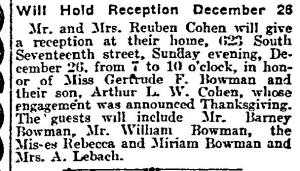

His oldest son Maurice married Edna Mayer on January 19, 1915. Their son Maurice Lester, Jr., was born January 30, 1917. According to the 1917 city directory, they were living at 4248 Spruce Street, and Maurice was working at the South Philadelphia Loan Office; on his draft registration that same year he described himself as self-employed as a broker.

Maurice Cohen World War I draft registration

On the 1920 census they were still living on Spruce Street, and Maurice’s occupation was pawnbroker.

Maurice Cohen and family 1920 census

In 1917 Stanley was still living at home and was the proprietor of a pawnshop at 2527 South 13th Street, according to his World War I draft registration. In the 1917 city directory he is listed as working at the South Philadelphia Money Loan Office, the same business where his brother Maurice was working and presumably the shop located at 2526 South 13th Street. He is also listed at the same business in 1921, living at 2114 [sic?] Green Street.

Stanley Cohen World War I draft registration

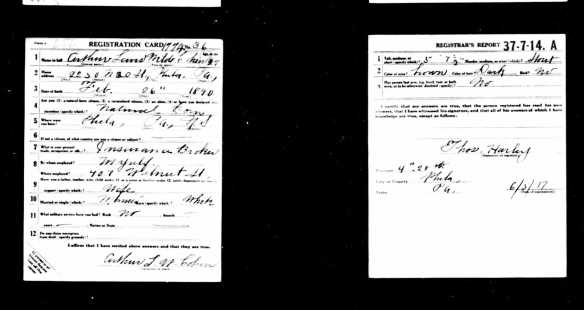

In 1917 my grandfather John was also living at home at 2116 Green Street and employed as an advertising salesman for the Morning Bulletin, according to his World War I draft registration.

John Cohen Sr. World War I draft registration

According to the 1918 city directory, John was in the United States Navy at that time. I have not yet found anything more specific about his military service.

In 1920, Emanuel, Eva (listed incorrectly as Edith), Stanley, John, and two servants were living at 2116 Green Street.

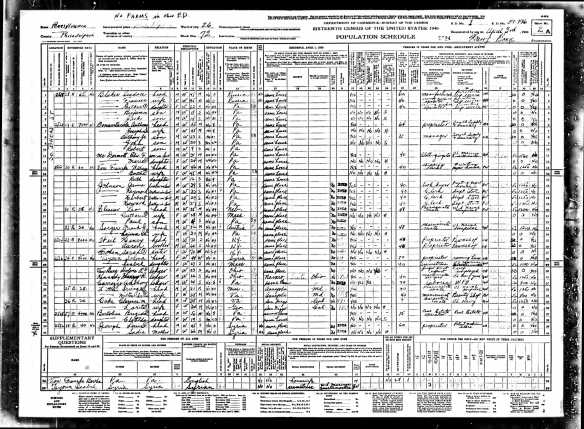

Emanuel Cohen and family 1920 census

Interestingly, in the 1921 city directory, Emanuel’s business was now classified as watches and jewelry. Had he left the pawnbroker business between 1920 and 1921, or was this just another way of describing his business?

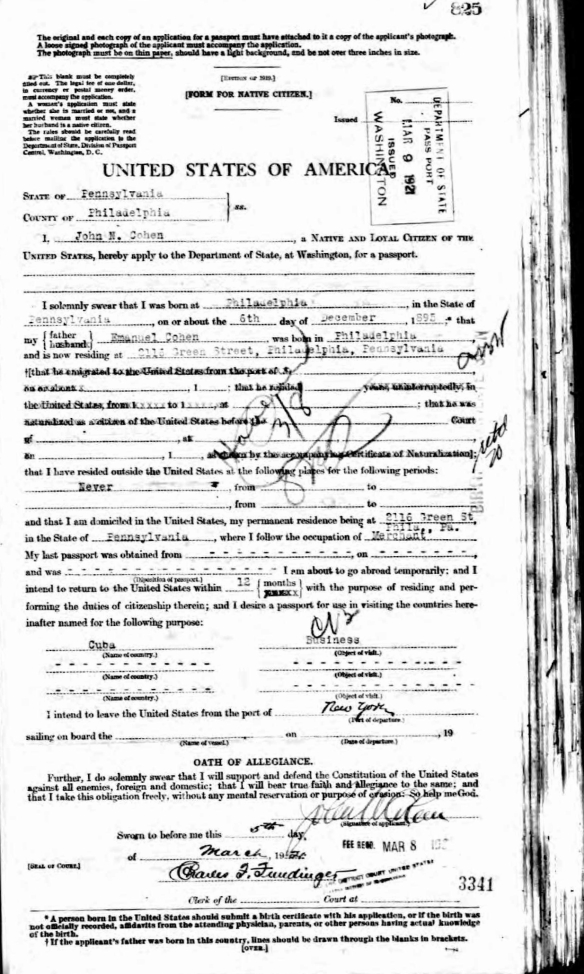

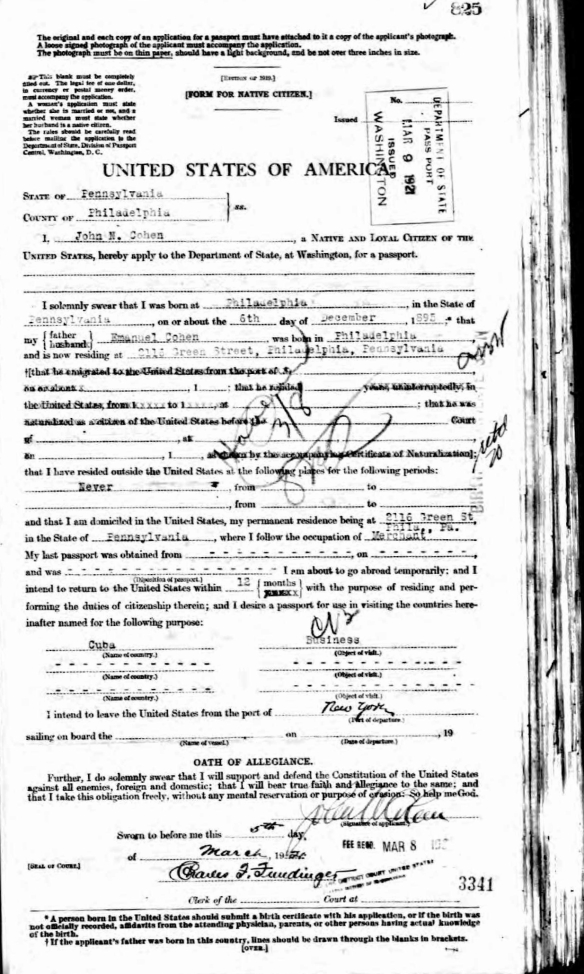

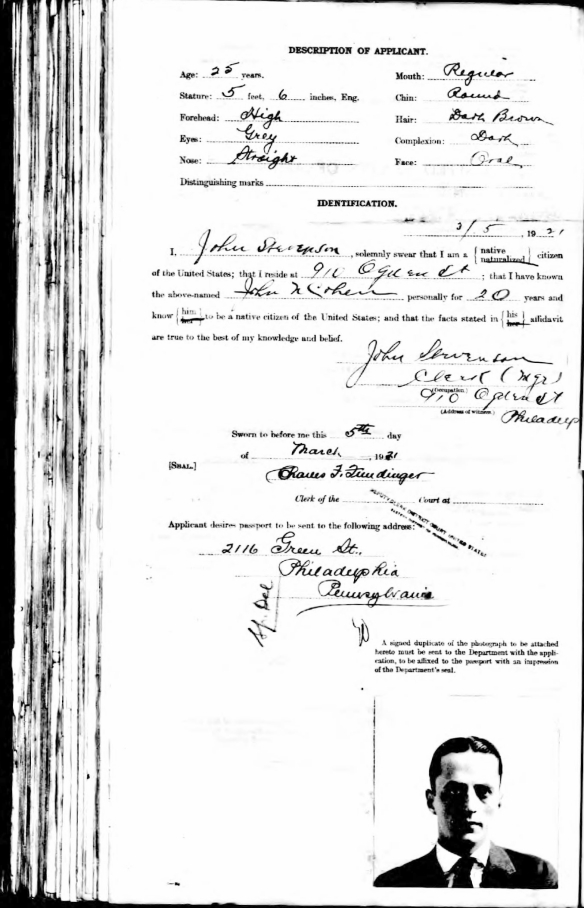

I didn’t think I would be able to find the answer, but then, to be honest, I stumbled upon it. I had found my grandfather John’s 1921 passport application almost a year ago and found it interesting that he was applying for a passport to go to Cuba for up to twelve months. I also found the similarity between his signature and my father’s signature rather remarkable.

John N. Cohen passport application 1921

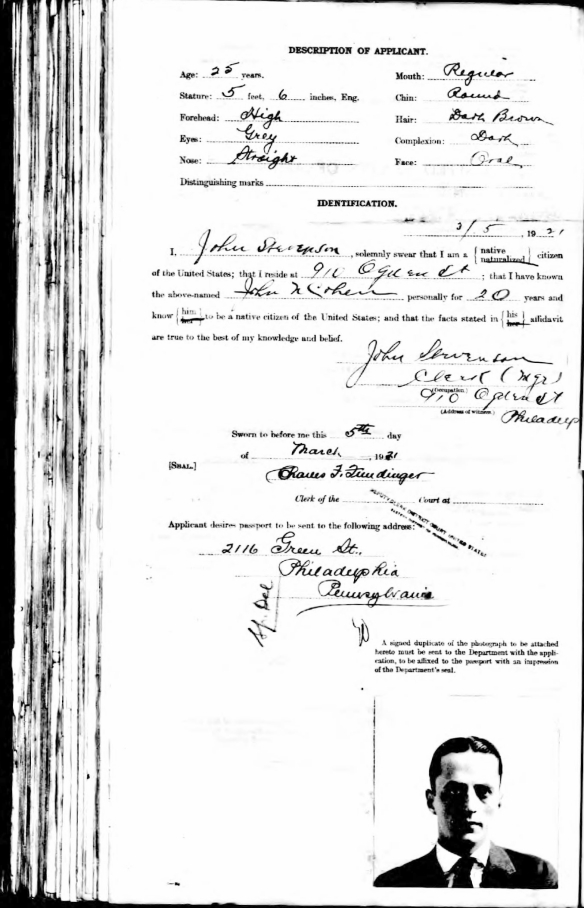

I had noticed that the page facing his application had a photograph of someone else, the person whose application preceded his in the database. So I went to the following page to see if his photograph appeared on that page, and sure enough it did. It also had a physical description of my grandfather: 5’ 6” tall, with a high forehead, straight nose, grey eyes, regular mouth, round chin, dark brown hair, dark complexion, and an oval face.

John N Cohen passport application page 2

What I had not noticed the first time I studied this document was the letter that appears on the facing page—a letter signed by my great-grandfather Emanuel, certifying that his son, John N. Cohen, was going to represent the interests of the “Commodore” in Cuba. The letter was on the stationery of the Commodore, located at 13th Street and Moyamensing Avenue, with the slogan “Our Policy One Price for All.” I had never heard this business mentioned or seen it named on any other document.

Letter by Emanuel Cohen May 21, 1921

After some work on newspapers.com, genealogybank.com and Google, I finally found an advertisement for the business:

This was a business owned or at least managed by my grandfather when he returned from the Navy to provide merchandise to veterans at a fair price. I found this ad interesting in several ways. First, I love that he sold suits “both snappy and conservative.” I also found it interesting that the ad proclaims that it has “no connection with any other store in Philadelphia.” Was this my grandfather’s way of asserting his independence from the family pawnshop business? Or was this some trademark issue involving a store with a similar name? (I did see ads for a furniture store advertising a living room set as The Commodore.) My father had never heard the store referred to by this name, but said he did recall that his father had a Navy friend whom he referred to as the Commodore who was his connection to the Navy Yard in Philadelphia. My father does remember visiting the store years later when his grandmother was managing it and selling only jewelry, not men’s clothing, snappy or otherwise.

The years between 1920 and 1930 were years of growth for Emanuel and Eva’s sons. In 1922, Maurice and Edna had a second son, Emanuel. On January 5, 1923, Stanley married Bessie Craig, who was fourteen years younger than Stanley. Their daughter Marjorie was born two years later in 1925.

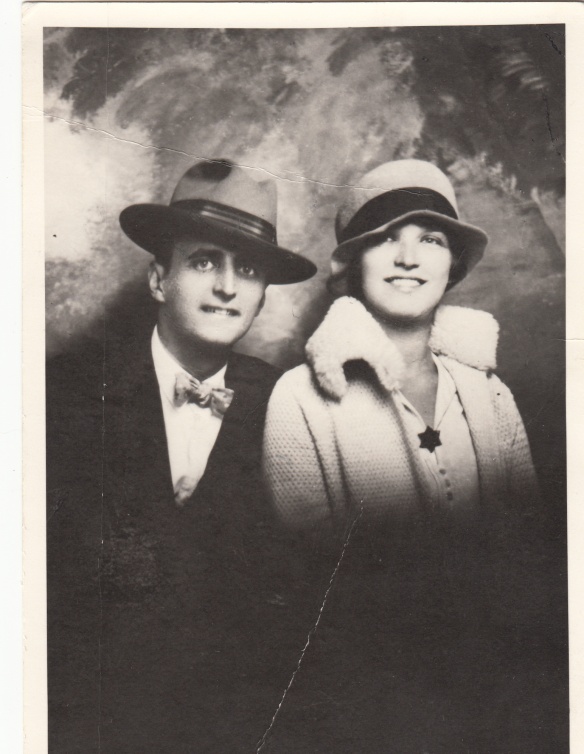

My grandparents, John Nusbaum Cohen, Sr., and Eva Schoenthal, were married on January 7, 1923, according to the family bible. (I assume they were married outside Pennsylvania since there is no marriage record in the Pennsylvania index for them) My aunt, Eva Hilda Cohen, was born January 13, 1924, and my father John, Jr., was born two years later. My father recalls that the family was also living on Green Street in 1924 when his sister was born and at 6625 North 17th Street when he was born. (There were no city directories available online for the years between 1922 and 1926.) (The fact that there were two Emanuels, two Maurices, three Evas, and two Johns in their family must have created some confusion, though Maurice, Jr, was called Junior and Emanuel II was called Buddy. My father was always called Johnny.)

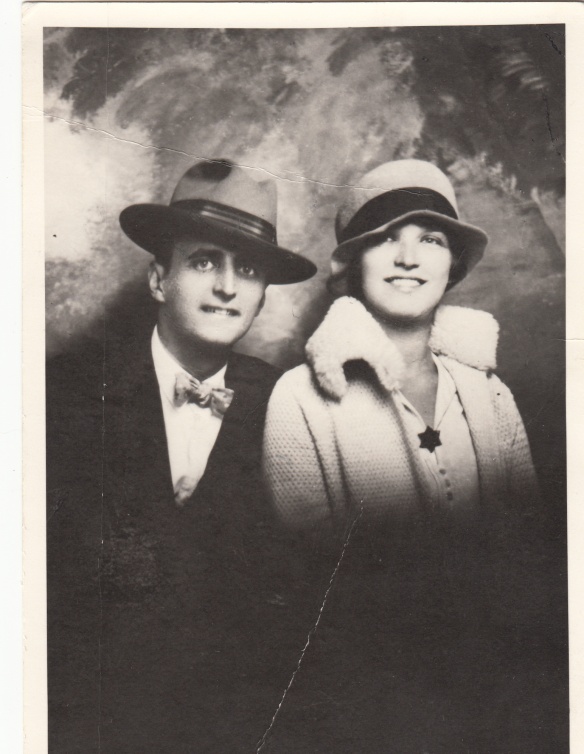

This is the only picture I have of my grandparents together. They were certainly a handsome couple. And they were certainly wearing “snappy” clothing! I am struck by the Star of David that my grandmother is wearing; they were not religious people, but obviously she felt a strong enough Jewish connection to be wearing such a large star.

John and Eva Cohen, My Paternal Grandparents

c. 1930

Eva Hilda Cohen

I have always loved this picture of my father; his face really has not changed in many ways. He still has those beautiful, piercing blue eyes.

My father at 9 months old

The reverse side of the photo above—inscribed “Taken a about 9 months, Johnny”

Another wonderful picture, capturing my father as a happy little toddler.

Although the next photograph is badly damaged, I am including it in large part to show the inscription on the back, “Johnny Boy.” My father said that his grandmother Eva May was the one to label the photographs, just as she was the one who made the entries for her children and grandchildren in the family bible. I like to think that I have inherited her role as a family historian and photograph archivist.

“Johnny Boy”

This photograph below captures my aunt as a young girl. She was a strong and independent person who always stood up for herself and knew what she wanted.

My Aunt, Eva Hilda Cohen

If the 1920s were years of growth, they were also years of loss. On February 21, 1927, my great-grandfather Emanuel died after a cholecystectomy (gall bladder removal, according to my ever-reliable medical consultant). It looks like the principal cause of death was pneumonia and either anemia or a hernia. It also says he suffered from diabetes mellitus. He was only 64 years old.

Emanuel Cohen death certificate 1927

These were also years of loss for the larger Cohen family; by the time Emanuel died in 1927, he had lost all but two of his siblings, Hannah and Abraham, and Hannah would die just a few months later. Although Jonas had died in 1902, Hart and Fanny in 1911, and Isaac in 1914, between 1923 and 1927 the family lost eight siblings: Joseph (1923), Elizabeth (1923), Lewis (1924), Maria (1925), Rachel (1925), Reuben (1926), and then Emanuel and Hannah in 1927. Of the thirteen children of Jacob and Sarah Cohen, only one remained after Emanuel and Hannah died, the baby Abraham.

The next decade, the 1930s, were also very challenging years for Eva, Emanuel’s widow, and her three sons. According to the 1930 census, Stanley was now working as a broker. My grandfather John listed his occupation as a clothing and jewelry merchant on the 1930 census, perhaps still working at The Commodore; he and his family were still living at 6625 North 17th Street at that time, which was about fifteen miles north of the Commodore location.

My grandparents, my aunt and my father on the 1930 census

I could not find Maurice on the 1930 census, unless he is the Maurice L. Cohen listed as living with a wife Celia, a son Lester, and a daughter Nannette. I dismissed this household many times, but since I cannot find him elsewhere and since his son’s middle name was Lester and his other son was Emanuel, which could have been heard by a census taker as Nanette, I suppose, I am inclined to think that this is probably Maurice’s listing, but perhaps not. At any rate, I was able to find Maurice’s death certificate. He died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head on August 14, 1931; family lore is that he had been suffering from cancer. He was only 43 years old, and his sons were fourteen and nine years old when he died.

Maurice Cohen death certificate 1931

Some years after Maurice’s death, his widow Edna moved to southern California. According to the 1940 census, she and her two sons, Maurice, Jr., and Emanuel, now called Philip, were living in Los Angeles, although the census indicates they were all still living in Philadelphia in 1935. My father recalls going to camp with both of his cousins in 1938, so I assume it was sometime after that that Edna and her sons moved away. My father said he never saw them again.

Edna Cohen and sons 1940 census

Maurice was not the only one to face serious medical problems during this time period. My grandfather John contracted multiple sclerosis also during this period. My grandmother, a sensitive and fragile person, was herself hospitalized and unable to care for her husband or her children, and so John, Sr., and his two children were taken care of by his mother, Emanuel’s widow, Eva May Seligman Cohen. Once again my great-grandmother opened her heart and her doors to care for family members as she had done over 25 years earlier for her brother-in-law Isaac and his son.

In 1936, my grandfather was admitted to a Veteran’s Administration facility in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, over forty miles away from Philadelphia. He lived the rest of his life until he died on May 2, 1946. He was 50 years old.

John Cohen, Sr. 1940 census

My great-grandmother continued to care for his children, my father and his sister, until she died on October 31, 1939, from heart disease. My father and aunt then lived with various other relatives until their mother was able to care for them again.

Eva May Seligman Cohen death certificate

Stanley, Maurice and John’s brother, did not face the terrible health issues faced by his brothers. In 1940 he was working as a pawnbroker, and according to his World War II draft registration in 1942, he was self-employed, calling his business Stanley’s Loan Office.

Stanley Cohen World War II draft registration

In the 1950s, Stanley and Bessie moved to Atlantic City, where he lived for the rest of his life. Bessie died in April, 1983, and Stanley died in July, 1987. He was 97 years old. I have located where his daughter was last residing and hope to find a way to contact her.

As for Maurice’s family, I don’t know very much about what happened to them after they moved to California. Edna died in 1979, and Maurice, Jr., in 1988. Both were still living in California when they died. Emanuel Philip was harder to track down, but I eventually found him as Bud Colton in the California death index. How, you might wonder, did I know that Bud Colton was the same person as Emanuel Cohen? Well, the death index listed his father’s surname as Cohen and his mother’s birth name as Mayer. In addition, he was always called Buddy by the family. Colton is fairly close to Cohen in pronunciation, and there was some family lore that he had in fact changed his name to something else. Bud served in the army during World War II as Bud Colton. He married Helga Jorgensen in April, 1957, when he was 34 and she was 49. Bud died in February, 1995, and is buried as a veteran at Los Angeles National Cemetery. I did not find any children of either Bud or Maurice, Jr.; although I found a few Maurice Cohens in the California marriage index, only one of those marriages seemed to have resulted in a child, and her birth certificate revealed that her father Maurice Cohen was not the one related to me. The other two Maurice Cohen marriages would have been fairly late in Maurice’s life (if in fact it was the same Maurice Cohen), and I found no evidence of any children from those marriages. Given the age of Helga when she married Bud, it also seems unlikely that that marriage resulted in any children.

It is rather sad that we know so little about my father’s paternal first cousins, but this was all I could find up to this point. I will keep looking and hope that more information will turn up. Perhaps in that mysterious suitcase I will find more pictures, more documents, more answers. Nevertheless, I know a great deal more now than I once did about my great-grandparents Emanuel and Eva Cohen and my paternal grandfather John Nusbaum Cohen.

Below is the headstone for my great-grandparents Emanuel and Eva May and for my grandfather, John N. Cohen, Sr., who were buried at Mt. Sinai Cemetery in Philadelphia. Maurice is also buried there, one section over.