And I am back from vacation. We had a wonderful time, and not having reliable internet access may have been a blessing. I couldn’t do any new research or posting to the blog so my brain had a chance to clear. Always a good thing. I did, however, have one more post “in the bank” that I prepared before I left, so here it is. I was awaiting a few more documents, hoping they would answer a few questions, and I received some while away that I have just reviewed.

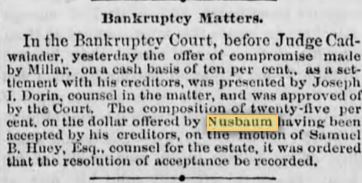

I wish I could post a somewhat more uplifting post for the holiday season, but I can’t deny the sad fact that some of my relatives suffered considerable sadness in their lives. On the other hand, researching and writing about the families of Leopold Nusbaum and his sister Mathilde Nusbaum Dinkelspiel only made me appreciate all my blessings. So in that sense it is perhaps appropriate. Nothing can make you appreciate all you have more than realizing how little others have.

So here is the story of two of the Nusbaum siblings, one of the brothers and one of the sisters of my three-times great-grandfather John Nusbaum.

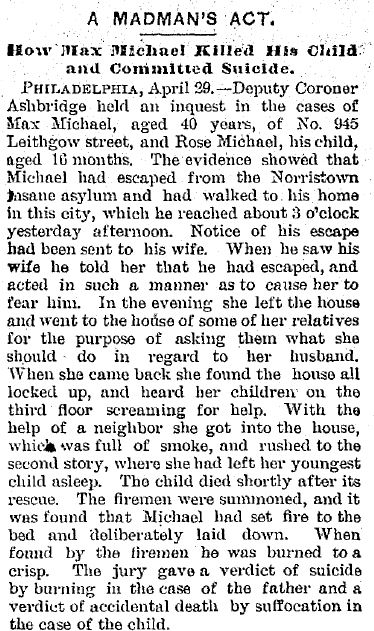

Leopold Nusbaum had died in 1866 when he was 58 years old, leaving his widow Rosa and daughter Francis (how she apparently spelled it for most of her life) behind. Leopold and Rosa had lost a son, Adolph, who died when he was just a young boy. Francis was only 16 when her father died. After Leopold died, Rosa and Francis moved from Harrisburg to Philadelphia and were living in 1870 with Rosa’s brother-in-law, John Nusbaum.

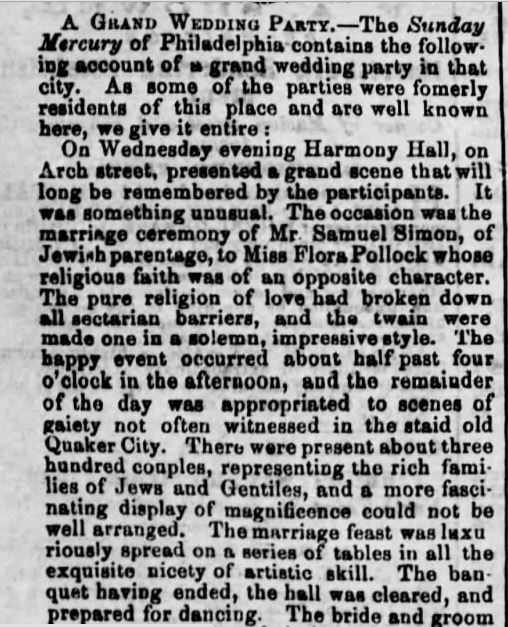

Late in 1870, Francis Nusbaum married Henry N. Frank. Henry, the son of Nathan and Caroline Frank, was born in Lewistown, Pennsylvania, where Leopold’s brother Maxwell Nusbaum and his family had once lived before relocating to Harrisburg. Henry’s father Nathan Frank was in the dry goods business, so the Nusbaums and Franks might have known each other from those earlier times. Nathan, Caroline, and their children had relocated to Philadelphia by 1870 and were living on Franklin Avenue right near the Simons, Wilers, and other members of the Nusbaum/Dreyfuss clan. Perhaps that is how Francis and Henry met, if not from an earlier family connection.

Not long after they were married, Henry and Francis must have moved back to Lewistown because their first child, Leopold, was born there on August 11, 1871. Leopold was obviously named for Francis’ father. A second child, Senie, was born in May 1876, and then another, Cora, was born in 1877. In 1880, Henry and Francis were living in Lewistown with their three young children as well as Francis’ mother Rosa and Henry’s father Nathan. Maybe Nathan was shuttling back and forth between Lewistown and Philadelphia because he is listed on the 1880 census in both places, once with Henry and Francis and then again with Caroline and their other children. Both Henry and his father Nathan listed their occupations as merchants.

Unfortunately, there is not much else I can find about Henry, Francis, or their children during the 1870s because Lewistown does not appear to have any directories on the ancestry.com city directory database. Lewistown’s population in 1880 was only a little more than three thousand people, which, while a 17% increase from its population of about 2700 in 1870, is still a fairly small town. It is about 60 miles from Harrisburg, however, and as

I’ve written before, well located for trade, so the Frank family must have thought that it was still a good place to have a business even if the rest of the family had relocated to Philadelphia.

Mathilde Nusbaum Dinkelspiels’ family is better documented. She and her husband Isaac had settled and stayed in Harrisburg, which is where they were living as the 1870s began. Isaac was working as a merchant. Both of their children were out of the house. Adolph was living in Peoria at the same address as his cousin Julius Nusbaum and working with him in John Nusbaum’s dry goods store in that city. On January 4, 1871, Adolph Dinkelspiel married Nancy Lyon in Peoria, and their daughter Eva was born a year later on January 25, 1872. Adolph and Nancy remained in Peoria, and by 1875 Adolph was listed as the “superintendent” of John Nusbaum’s store. (Julius does not appear in the 1875 directory, though he does reappear in Peoria in 1876.)

On November 28, 1879, his daughter Eva died from scarlet fever. She was not quite eight years old. Adolph and Nancy did not have other children, and this must have been a devastating loss.

In fact, shortly thereafter Adolph, who had been in Peoria for over sixteen years, and Nancy, who was born there and still had family there, left Peoria and relocated to Philadelphia. On the 1880 census, Adolph was working as a clothing salesman and Nancy as a barber. (At least that’s what I think it says. What do you think?) Perhaps Adolph and Nancy left to find better opportunities or perhaps they left to escape the painful memories. Whatever took them away from Peoria, however, was enough that they never lived there again.

Adolph and Nancy did not remain in Philadelphia for very long, however. By 1882 Adolph and Nancy had relocated to St. Louis, Missouri, where Adolph worked as a bookkeeper for many years. They remained in St. Louis for the rest of their lives. Adolph died on November 25, 1896, and Nancy less than a year and a half later on March 5, 1898. Adolph was only 53, and Nancy was not even fifty years old.

My cousin-by-marriage Ned Lewison sent me a copy of Nancy’s obituary from the March 7, 1898 Peoria Evening Star. It reported the following information about Nancy and Adolph Dinkelspiel:

“She married Adolph Dinkelspiel, at that time manager of the Philadelphia store on the corner of Main and Adams Street, one of the leading dry goods houses in Peoria. When the house failed, they removed to St. Louis and lived happily together until the death of Mr. Dinkelspiel, when his widow came to this city. But she preferred St. Louis for a residence, and although she made frequent visits to Peoria, she did not take up residence here.”

I found two points of interest in this obituary. One, there is no mention of their daughter Eva. And two, it reveals that the Nusbaum store in Peoria had closed, prompting Nancy and Adolph to relocate. Thus, Adolph and Nancy not only suffered a terrible personal loss, like many others in the family and in the country, they were negatively affected by the economic conditions of the 1870s.

Nancy and Adolph are both buried, along with their daughter Eva, in Peoria. Only death, it seems, could bring them back to Peoria.

Adolph’s sisters Paulina and Sophia Dinkelspiel did not have lives quite as sad as that of their brother, but they did have their share of heartbreak. Sophia, who had married Herman Marks in 1869, and was living in Harrisburg, had a child Leon who was born on October 15, 1870. Leon died when he was just two years old on October 24, 1872. I do not know the cause of death because the only record I have for Leon at the moment is his headstone. (Ned’ s research uncovered yet another child who died young, May Marks, but I cannot find any record for her.)

Sophia and Herman did have three other children in the 1870s who did survive: Hattie, born May 30, 1873, just seven months after Leon died; Jennie, born August 24, 1876; and Edgar, born August 27, 1879. Herman worked as a clothing merchant, and during the 1870s the family lived at the same address as the store, 435 Market Street in Harrisburg.

Paulina (Dinkelspiel) and Moses Simon, meanwhile, were still in Baltimore in the 1870s. In 1870 Moses was a dealer “in all kinds of leather,” according to the 1870 census. At first I thought that Moses and Paulina had relocated to Philadelphia in 1871 because I found a Moses Simon in the Philadelphia directories for the years starting in 1871 who was living near the other family members and dealing in men’s clothing. But since Moses and Paulina Simon are listed as living in Baltimore for the 1880 census and since Moses was a liquor dealer in Baltimore on that census, I realized that I had been confused and returned to look for Moses in Baltimore directories for that decade.

Sure enough, beginning in 1871 Moses was in the liquor business, making me wonder whether the 1870 census taker had heard “liquor” as “leather.” After all, who says they deal in all kinds of leather? All kinds of liquor makes more sense. Thus, like the other members of the next generation, Adolphus and Simon Nusbaum in Peoria, Leman Simon in Pittsburgh, and Albert Nusbaum in Philadelphia, Moses Simon had become a liquor dealer.

http://www.gettyimages.com/detail/114527609

Moses and Paulina had a fourth child in 1872, Nellie. The other children of Moses and Paulina were growing up in the 1870s. By the end of the decade, Joseph was eighteen, Leon was fourteen, Flora was twelve, and little Nellie was eight.

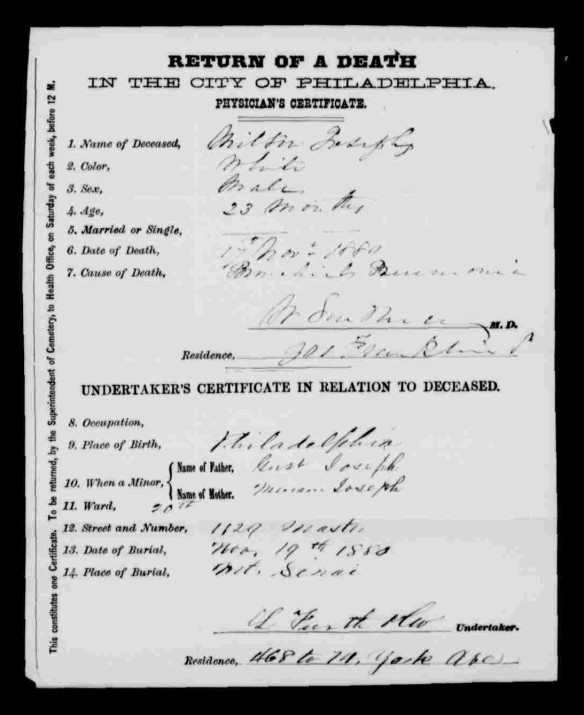

Ned Lewison, my more experienced colleague and Dinkelspiel cousin, found a fifth child Albert born in 1875 who died August 25, 1876 and a sixth child Miriam born in July 1877 who died October 30, 1878, both of whom are buried at Oheb Shalom cemetery in Harrisburg, where their parents would also later be buried. Thus, Paulina lost two babies in the 1870s. For her parents, Mathilde and Isaac, that meant the deaths of four grandchildren in the 1870s alone.

As for Mathilde and Isaac Dinkelspiel themselves, although they began and ended the decade in Harrisburg, my research suggests that for at least part of that decade, they had moved to Baltimore. Isaac has no listing in the 1875 and 1876 Harrisburg directories (there were no directories for Harrisburg on line for the years between 1870 and 1874), but he does show up again in the Harrisburg directories for 1877 and 1878. When I broadened the geographic scope of my search, I found an Isaac Dinkelspiel listed in the Baltimore directories for the years 1872, 1873, 1874, and 1875 as a liquor dealer. This seemed like it could not be coincidental. It’s such an unusual name, and Isaac’s son-in-law Moses Simon was a liquor dealer in Baltimore. It seems that for at least four years, Isaac and Mathilde had left Harrisburg for Baltimore, leaving their other daughter Sophia and her husband Herman Marks in charge of the business at 435 Market Street in Harrisburg, where Isaac and Mathilde lived when they returned to Harrisburg in 1877.

![Market Street in Harrisburg 1910 By Wrightchr at en.wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/hb_market_street.jpg?w=584&h=351)

Market Street in Harrisburg 1910

By Wrightchr at en.wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The extended Dinkelspiel family as well as the Nusbaum family suffered another major loss before the end of the decade. According to Ned Lewison’s research, Mathilde Nusbaum Dinkelspiel died on June 20, 1878. Another Nusbaum sibling had died, leaving only John and Ernst alive of the original six who had emigrated from Germany to America; Maxwell, Leopold, Isaac, and now Mathilde were gone. Mathilde is buried at Oheb Shalom cemetery in Harrisburg.

What happened to Isaac Dinkelspiel after his wife Mathilde died? Although Isaac appeared in the 1880 Harrisburg directory at 435 Market Street, the same address as his son-in-law Herman and daughter Sophia (Dinkelspiel) Marks, he does not appear with them on the 1880 census at that address. In fact, I cannot find him living with any of his children or anywhere else on the 1880 census, although he is again listed in the Harrisburg directory at 435 Market Street for every year between 1880 and 1889 (except 1881, which is not included in the collection on ancestry.com). I assume the omission from the census is just that—an omission, and that Isaac was in fact living with Sophia and Herman during 1880 and until he died on October 26, 1889, in Harrisburg. He is buried with his wife Mathilde at Oheb Shalom cemetery in Harrisburg.

Thus, the Dinkelspiels certainly suffered greatly in the 18070s. Five children died in the 1870s—Eva Dinkelspiel, May Marks, Leon Marks, Albert Simon, and Miriam Simon. And their grandmother, Mathilde Nusbaum Dinkelspiel, also passed away, joining her brothers Maxwell, Leopold, and Isaac, leaving only John and Ernst left of the six Nusbaum siblings who left Schopfloch beginning in the 1840s to come to America.

And so I leave you with this thought as we start looking forward to a New Year. Don’t take your children or your grandchildren for granted. Cherish every moment you get to share with them. And be grateful for modern medicine and the way it has substantially reduced the risks of children being taken from us so cruelly.

![Lewistown Town Square By KATMAAN (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/1024px-ltownsquare1.jpg?w=584&h=438)

![Market Street in Harrisburg 1910 By Wrightchr at en.wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/hb_market_street.jpg?w=584&h=351)

![Ancestry.com. U.S. IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1862-1918 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2008.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/john-nusbaum-1862-tax.jpg?w=584&h=471)

![Lottie Nusbaum death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/lottie-nusbaum-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=552)

![Nusbaum Brothers and Company 1867 Philadelphia Directory Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/nusbaum-bros-1867.jpg?w=501&h=77)