Peoria, Illinois 1867

http://www.history-map.com/picture/004/Illinois-Peoria.htm

My father’s family has lived in some places that were surprising to me—Cohens in Des Moines and Kansas City, Seligmans in Santa Fe, and Nusbaums in Harrisburg and other small towns in Pennsylvania. In the 1860s, some of the Nusbaums and their Dreyfuss, Dinkelspiel and Simon relatives ended up in Peoria. All I knew about Peoria was the old line, “Will it play in Peoria?” As explained on the official website for Peoria, Illinois:

The phrase “Will It Play in Peoria?” originated in the early ’20s and ’30s during the US vaudeville era. At that time, Peoria was one of the country’s most important stops for vaudeville acts and performances. If an act did well in Peoria, vaudeville companies knew that it would work throughout the nation. The saying was popularized by movies with Groucho Marx, and on radio programs such as Jack Benny and Fibber McGee. Because of it’s [sic] location and demographics, Peoria has since become a well known test market to gauge the popularity of products and ideas nationwide.

Peoria has become a symbol of mainstream America, a short-hand way of referring to the typical “Middle American,” as Richard Nixon might say. So perhaps I should not be surprised that my entrepreneurial Nusbaum/Dreyfuss ancestors struck out for Peoria after succeeding in Harrisburg and Philadelphia. It was a new market to exploit as the US population continued to expand and move west.

But were there Jews there in the 1860s? Surprisingly, there was an established Jewish community. According to the Jewish Virtual Library’s entry for Illinois, “The oldest Jewish community [in Illinois] outside of Chicago is Peoria, where the first Jews arrived in 1847. A benevolent society was organized in 1852 and the first congregation, Anshai Emeth, was formed in 1859.” The website for Anshai Emeth reveals only a little bit more about the early history of Jews in Peoria:

The first Jewish settlers came to Peoria in approximately 1847. They soon organized themselves into groups and worshiped in private homes. Early settlers included Jacob Liebenstein (1848), Henry Ullman and Leopold Rosenfeld (1849), Abraham Schradski and Leopold Ballenberg (1851), and Aaron, Harry and David Ulman (1852), and Henry Schwabacker. Many of their descendants continue to live in the Peoria community. Religious school classes were organized by 1852. In the same year, these Jewish settlers organized a burial association and bought a lot for the use as a cemetery. With this purchase grew the first organized Jewish life in Peoria. Religious services were held in various halls including Washington House on North Washington Street. Abraham Frank, A. Rosenblat, Hart Ancker, A. Ackerland, Arnold Goodheart, and Abraham Solomon formally organized a congregation in 1859 and named themselves “Anshai Emeth,” or “People of Truth.”

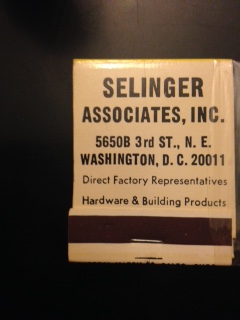

Although in 1860 the Nussbaum/Dreyfuss clan was settled either in Harrisburg or Philadelphia, as early as 1862 some of the next generation began moving to Peoria. Paulina Dinkelspiel, the daughter of Mathilde Nusbaum and Isaac Dinkelspiel, married a man named Moses Simon in 1862. Moses was born in 1835 in what is now the Hesse region of Germany. He and his brothers Leman and Samuel had a business in Peoria as early as 1861, as did their father Sampson.

But as the directory indicated, Moses was residing in Harrisburg in 1861. Perhaps Moses had a business relationship with the Nusbaum business; perhaps that is how he obtained his merchandise for their business in Peoria. But while living in Harrisburg, Moses must have met Paulina. And after they were married, they moved to Peoria where their first two children were born, Joseph in 1862 and Francis in 1864.

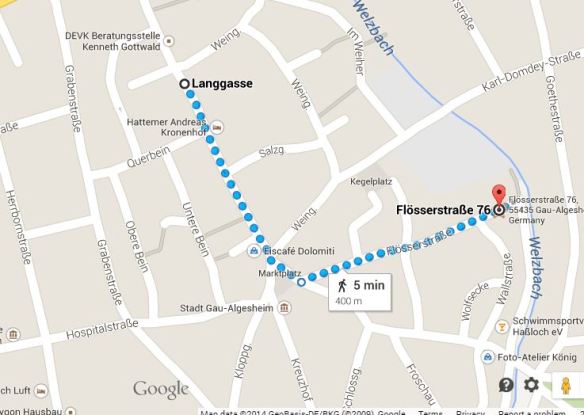

Not long after, Paulina’s younger brother Adolph Dinkenspiel arrived in Peoria. Although he is not listed in the 1861 directory, he does appear in the 1863 directory. While the Simon brothers and their father were all living at 95 North Adams Street that year, Adolph was boarding at the corner of North Adams and Hamilton Street, right down the block, and working as a clerk at 73 Main Street.

Adams Street, Peoria

http://www.epodunk.com/cgi-bin/genInfo.php?locIndex=6554

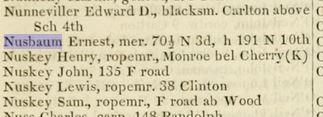

What was going on at 73 Main Street? The Simon Brothers business was at 5 North Adams Street, so young Adolph was not working for his sister’s husband. A look at the 1863 directory for Peoria under N revealed that John Nusbaum, my three-times great-grandfather, had a business at that location as a “fancy and staple dry goods merchant.” Although John was still residing in Philadelphia, he is listed in the directory as are two of his sons. His oldest son Adolphus, was residing at Peoria House, a hotel, I assume, and working for a firm called “Adler, N. & Higbie.” A further look through the 1863 directory uncovered a listing for a distillery called Adler, Nusbaum & Higbie. John’s second son Simon is also listed in the 1863 Peoria directory, working as the business manager of his father’s store at 73 Main Street with his cousin Adolph Dinkenspiel and residing at 36 North Adams Street.

By 1863, the country was in the throes of the Civil War, yet it appears that my Peoria relatives were not serving in the war. I did find a document that indicates that both Simon and Adolphus Nusbaum registered for the draft in 1863 for the Civil War, but I cannot find any other documentation of their service in that war.

National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Consolidated Lists of Civil War Draft Registration Records (Provost Marshal General’s Bureau; Consolidated Enrollment Lists, 1863-1865); Record Group: 110, Records of the Provost Marshal General’s Bureau (Civil War); Collection Name: Consolidated Enrollment Lists, 1863-1865 (Civil War Union Draft Records); ARC Identifier: 4213514; Archive Volume Number: 2 of 5

Not one of these young men in the family appears in any of the databases listing those who served. I searched not only Ancestry, Fold3, and FamilySearch, but also the National Park Service database, the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System, found here, and found nothing.

How had they all avoided service? Simon and Adolphus registered, but I can’t even find registration evidence for Adolph Dinkelspiel. The Draft Act of 1863 applied to all male citizens between 20 and 45 years old; in 1863 Adolphus was 21 and Simon and Adolph were 20. Adolphus and Simon were born in the US and were thus citizens, but Adolph Dinkelspiel was born in Baden. However, the Draft Act also applied to men who intended to become citizens. Perhaps Adolph avoided registration by not declaring such an intention. But how would his cousins Adolphus and Simon have avoided service? Apparently there were two ways to avoid being drafted: hire a substitute or pay $300. Perhaps that’s what the two Nusbaum brothers did. Or maybe I just haven’t found the documentation of their service. See also Michael T. Meier, “Civil War Draft Records: Exemptions and Enrollments,” Prologue Magazine (Winter, 1994) found online here.

All three of John’s sons were listed in the 1865 Peoria directory. Julius joined Simon as a clerk at the Nusbaum dry goods store, now located at the corner of North Adams and Main Street, two blocks up from its 1863 location. Adolphus, although still listed in the directory, was reported to be living in Philadelphia in 1865, but still associated with the Adler, Nusbaum & Higbie firm. In addition, John’s older brother Isaac is listed in the 1865 Peoria directory, boarding at 36 North Adams Street, the same address given for Julius. This is the first document evidencing Isaac’s presence in the US, so perhaps he was a late arrival and sent to Peoria to keep an eye on his nephews Julius and Simon Nusbaum and Adolph Dinkelspiel, who were single and only 17, 22, and 22 respectively in 1865.

Thus, in 1865, there were four male members of the extended Nusbaum family living in Peoria. Some members of the clan had left by then. Moses and Paulina (Dinkelspiel) Simon and Moses’ brothers Leman and Samuel and their father Sampson were gone from Peoria. Moses and Paulina had relocated to Baltimore where Moses was a “fancy goods” merchant. They had two more children between 1865 and 1870: Leon was born in 1866, and Flora in 1868, both born in Baltimore. On the 1870 census, Moses described himself as a dealer in all kinds of leather. [1] Thus, Moses Simon who started the migration of the Nusbaums to Peoria was himself gone by 1865.

Adolphus was not listed as living in Peoria in 1865, but he did eventually return to Peoria in 1868. There is an 1864 IRS tax report that lists the income for Adolphus and for the Adler, Nusbaum & Higbie distillery, so Adolphus was still in business in 1864 in Peoria. The 1865 Peoria directory reported that he was living in Philadelphia though still in business in Peoria.

In 1867 the only members of the Nussbaum/Dreyfuss/Dinkelspiel/Simon clan listed as living in Peoria were Isaac Nusbaum, Julius Nusbaum, and Adolph Dinkelspiel. However, the 1868 directory lists Isaac, Julius, S. (Simon?) and A. (Adolphus?) Nusbaum as well as Adolph Dinkelspiel. The four younger men are also listed in the 1870 directory. Simon and Adolphus were now in the distillery business together under the name Union Mills Distillery, and Julius was still working in his father’s “staple and fancy dry goods” business along with his cousin Adolph Dinkelspiel. Thus, three of my great-great-grandmother’s brothers as well as my first cousin four times removed, Isaac Dinkenspiel, were living in Peoria in 1870.

Isaac Nusbaum, their uncle, had died in January, 1870. He was not yet sixty years old. I could find no actual record of his death aside from the entry in the Nusbaum family bible and this rather peculiar news article from the January 25, 1870 Peoria Daily Transcript.

What does this mean? Why would his brother John have ordered the body returned to Peoria? Why had it first been en route to Philadelphia? How did Isaac die? There was no obituary. Isaac is a mystery to me. I don’t know where he was before 1865. It appears that he never married or had children. If it had not been for the family bible, I might never have even known to look for him.

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=pv&GRid=143048598&PIpi=117463912

Note says he is buried between two unrelated people.

By 1870, the four young Nusbaum descendants were grown men. Even the youngest, Julius, was 22. All four would spend the next decade in Peoria as well; two of them would spend most of the rest of their lives there.

So yes, it played well in Peoria for the Nusbaum/Dreyfuss family.

[1] For some reason on the second enumeration of the 1870 census, Moses and his brothers Samuel and Leman are listed with their parents in Philadelphia; I assume that the parents were confused when asked about the members of their family and reported all three sons as living with them when in fact all three sons were married by then and living with their wives and children.