Thanks to my friend Aaron Knappstein and my cousin Richard Bloomfield, an old brick wall has recently come down. Over seven years ago I wrote about the tragic story of Meier Katzenstein and his family. You can find all the sources, citations, and details here. But I will briefly outline their story.

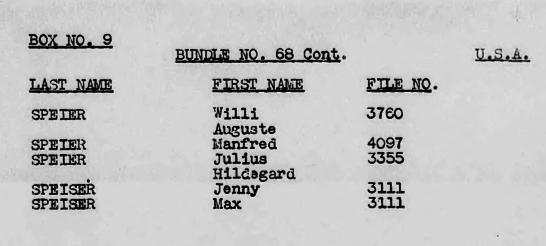

Meier, my great-grandmother Hilda Katzenstein Schoenthal’s first cousin, lost his first wife Auguste Wolf in 1876, shortly after she gave birth to their son August Felix Katzenstein. Meier remarried and had two more children with his second wife Bertha Speier: Julius Katzenstein, born in 1879, and Ida Katzenstein, born in 1880. Both Ida and her mother Bertha died in April 1881, less than a year after Ida’s birth. Meier was left with two young sons, August, who was five years old, and Julius, who was two.

And then Meier himself died three years later in 1884, leaving August and Julius orphaned at eight and five, respectively. I couldn’t imagine what had happened to those two little boys. Who took care of them? What happened to them? This post will follow up on August, and the one to follow will be about his half-brother Julius.

I had been able to find out some of what happened to August as an adult when I initially wrote about him over seven years. He had married his first cousin, once removed, Rosa Bachenheimer in Kirchain, Germany, in 1900 when he was twenty-four years old. August and Rosa had two children, Margarete and Hans-Peter. All four of them were killed by the Nazis during the Holocaust. I knew that much, but there were still some gaping holes in my research. Where had August lived after his father died? Did he have any grandchildren? If so, did they survive the Holocaust?

So I went back now to to double-check my research and see if I could find anything more about August Felix Katzenstein and his family. I am so glad I did.

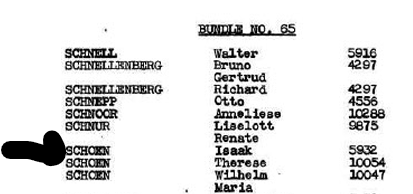

First, I learned at Yad Vashem that August and Rosa’s daughter Margarete had married Rudolf Loewenstein and had had two children with him: Klaus, born March 16, 1930, in Soest, Germany, and Klara, born June 9, 1932, in Soest, Germany. Unfortunately, Rudolf, Margarete and their two young children were also killed along with their grandparents and uncle during the Holocaust.

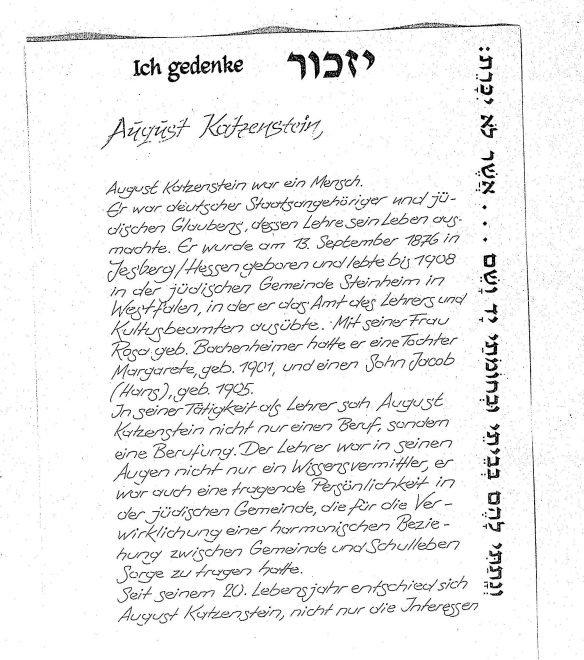

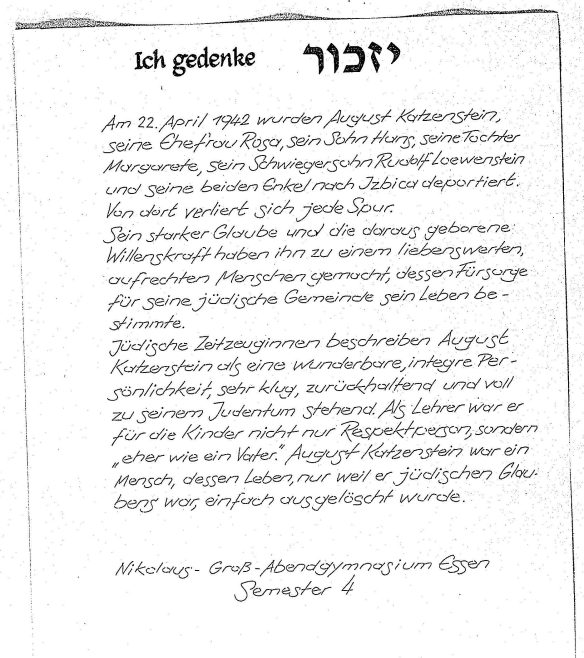

Then I found this Stolpersteine biography of August Katzenstein on a website about the history of the community of Essen, revised in 2024 by Mr. and Mrs. Hülskemper-Niemannn. It provides in part, as translated by Google Translate:

August Katzenstein was orphaned at a very early age. He then lived for a long time in the household of the parents of his future wife Rosa Bachenheimer from Kirchhain, whom he married around the turn of the century. The couple had two children: Margarethe (1901, later Loewenstein) and Hans (1905). August Katzenstein moved with his family to Steele in 1908 and took up a position as a teacher in the one-class Jewish elementary school at Isinger Tor. …

After 1933, the Katzensteins’ lives changed radically. In 1937, the Gestapo arrested the couple because they were allegedly managing the assets of a dissolved Jewish organization. After a search of their apartment and rigorous interrogation and warnings, the couple were released. Even worse happened to August Katzenstein, who taught at the Jewish elementary school in Essen on Sachsenstrasse after the Jewish elementary school in Steele was closed, during and after the November pogrom. The apartment on Grendtor (then Ruhrstrasse) was destroyed and looted, and he and his disabled son Hans were arrested. While the 62-year-old father was released from police prison after 11 days, Hans was taken to Dachau despite written requests from his parents, from where he was only released after four weeks.

In the autumn of 1941, the deportation of Jews began across the Reich, including in Essen. … Half a year later, Katzenstein and his entire family were deported to Izbica.

So now I know who had taken care of August after his father died: Rosa’s parents Sussman Bachenheimer and his wife Esther Ruelf, my second cousin, twice removed. I wrote about them here. I also now know that August had become a teacher and lived in Steele, Germany, a suburb of Essen, Germany.

I found additional information about August and his family at Yad Vashem. The website has been updated since I had last researched August Katzenstein, and I found these documents I had not seen before from the Yizkor Book for the Jews of the Essen community who had been killed during the Holocaust. I asked my cousin Richard Bloomfield to translate these pages, and he graciously (and quickly!) agreed to do so.

Richard’s translation provides:

Richard’s translation provides:

August Katzenstein was a Mensch.

He was a German citizen and of the Jewish faith, whose teachings shaped his life. He was born on September 13, 1876, in Jesberg/Hesse and lived in the Jewish community of Steinheim in Westphalia until 1908, where he held the office of teacher and religious official. With his wife Rosa, née Bachenheimer, he had a daughter Margarete, born in 1901, and a son Jacob (Hans), born in 1905.

August Katzenstein saw his work as a teacher not just as a profession, but as a vocation. In his eyes, the teacher was not only an imparter of knowledge, he was also a leading figure in the Jewish community who had to ensure a harmonious relationship between the community and school life.

Beginning at the age of 20, August Katzenstein decided to represent not only the interests of his community and pupils, but also those of German citizens of the Jewish faith as a whole.

He joined the “Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith” “Central-Verein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens”.

Until he moved to Essen in 1908, he was a representative of the C.-V. local group in Steinheim.

After moving to Essen Steele, he taught at the Jewish elementary school there. The importance that Katzenstein attached to the new self-image of Jews as German citizens of the Jewish faith can be seen in his speech on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Jewish school, in which he states,

“For 50 years now, the youth of the Jewish community has received their education in the Jewish school to become faithful Israelites and loyal citizens who love their fatherland, in addition to their general education. May the Jewish school continue to work beneficially for God, for the fatherland and for humanity, true to its guiding principles.”

The mission of the independent order “Bnai Brith” founded in the USA, spiritual self-education, the promotion of science and art, help for the persecuted and needy and the defense of Jewish citizens in the event of anti-Semitic attacks led August Katzenstein to join the Glück-Auf-Lodge of “Bnai Brith” in Essen in 1911 and of which he was president until April 1935.

Until his retirement in 1937, he also headed the Jewish relief organization in Essen-Steele. But despite his retirement, he did not neglect the members of the community whose employ he had left.

The ban and immediate dissolution of the “Bnai Brith” order by Himmler’s decree of April 10, 1937, resulted in August Katzenstein’s arrest on April 19, 1937, after his apartment and all the rooms of the Glück-Auf-Loge had already been searched two days earlier.

August Katzenstein then had to endure hours of interrogation under threat of state police measures. He was forced to sign a declaration that he had no further property belonging to the Glück-Auf-Lodge at his disposal and that he was not aware of where further material might be hidden, as documented in the Gestapo protocol of the same day.

During the so-called Reichskristallnacht on November 9, 1938, the Katzenstein family’s home at Ruhrstrasse 24 was also severely damaged. One day later, August Katzenstein and his disabled son were arrested again. They were held in the police prison in Essen until November 19, 1938. After his release, August Katzenstein wrote a letter to the Gestapo asking them to release his son, who had been sent to Dachau concentration camp. His son Jacob (Hans) then returned on December 21, 1938.

However, not only the care of his family, but also the suffering of the community entrusted to him had become his life’s purpose. Even the destruction of the school and synagogue as the center of the community during the November pogrom could not break August Katzenstein’s will to live in the Jewish faith.

In January 1939, August Katzenstein carried out his last community-related activity, officiating at the wedding of a young couple in the wife’s parental home.

On April 22, 1942, August Katzenstein, his wife Rosa, his son Hans, his daughter Margarete, his son-in-law Rudolf Loewenstein and his two grandchildren were deported to Izbica. No trace of them remains.

His strong faith and the willpower born of it made him a lovable, upright person whose care for his Jewish community defined his life.

Contemporary Jewish witnesses describe August Katzenstein as a wonderful person of integrity, very wise, reserved and fully committed to his Judaism. As a teacher, he was not only a person of respect for the children, but “more like a father.” August Katzenstein was a man whose life was simply snuffed out because he was Jewish.

Nikolaus-Gross, Abendgymnasium Essen, Semester 4

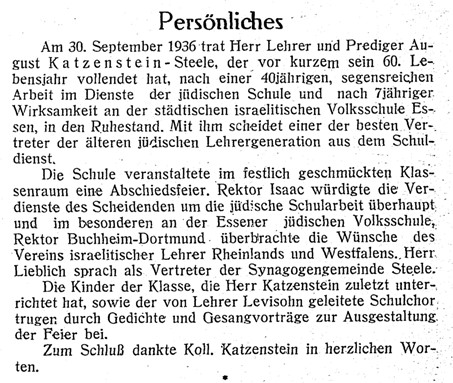

I wondered whether August’s “retirement” from teaching was voluntary or forced upon him by the Nazis, and although it’s still not clear, Richard also found this article about August’s retirement published on November 1, 1936, in the Jüdische Schulzeitung [Monthly journal for education, instruction and school policy; official publication of the Reich Association of Jewish Teachers’ Associations], (p.6):

Richard translated the article for me:

On September 30, 1936, after 40 years of beneficial work in the service of Jewish schools and 7 years of work at the local Jewish elementary school in Essen, teacher and preacher August Katzenstein of Essen-Steele, who recently turned 60, retired. With him, one of the best representatives of the older Jewish generation of teachers leaves the teaching profession.

The school held a farewell party in the festively decorated classroom. Principal Isaac paid tribute to the departing teacher’s services to Jewish schools in general and to the Jewish Elementary School in Essen in particular. Principal Buchheim of Dortmund conveyed the wishes of the Association of Israelite Teachers of the Rhineland and Westphalia. Mr. Lieblich spoke as a representative of the Steele Synagogue community.

The children of the class that Mr. Katzenstein taught last, as well as the school choir led by teacher Levisohn, contributed to the ceremony with poems and songs.

Finally, colleague Katzenstein gave a heartfelt thank you.

Obviously, August was a well-loved, well-respected teacher and community leader. His early childhood was quite miserable—losing his mother, then his stepmother and half-sister, then his father—all before he was nine years old. But despite that tragic beginning, he lived a full and productive life, filled with meaning, faith, family, and love. How someone recovers from so much tragedy is amazing to me.

But then the Nazis came to power and destroyed August’s life and his family. I am so glad I went back to see if I could learn more about his life, and I am so grateful to Richard for his translation of the documents from the Essen Yizkor Book and for finding the article about August’s retirement. I found comfort in knowing that despite his tragic beginning and ending, August found fulfillment and meaning in his life.

But what about his younger brother Julius? I had known even less about him when I first researched this family. I couldn’t find anything that revealed what happened to him after his parents died. I couldn’t find a marriage record, a death record, a birth record for any children—-not one thing. Fortunately, he was not listed at Yad Vashem, so presumably had not shared the fate of his brother August. But where had he gone? Who had taken care of this little orphaned boy?

I will report on what I’ve learned about Julius in my next post.