The further I delve into the story of my ancestors, the more aware I am of how much the lives of women have changed in the last 100 years—actually, more like the last 50 years, but since I am focusing on the women born between 1850 and 1900 right now, the 100 year line seems more appropriate. I’ve said numerous times that women are harder to research because they changed their names when they married. If you cannot figure out who they married, then they just disappear and their stories are never completed.

I obviously have a personal perspective on the question of taking on a new name when you marry. When I married back in 1976, most women still took their husband’s names when they married, but some women were starting to resist and keeping their birth names. Some women argued that keeping your father’s name was just as much a concession to male dominance as taking your husband’s name. I struggled with this issue; I was never a radical or a pioneer. But in the end, I wanted to keep my name. My reasons were varied; some of it was definitely based on the values of the women’s movement that was exploding around me during my years in college. Mostly, however, it was just about holding on to my identity, the one I had had for over twenty years. How could I not be Amy Cohen? It just felt wrong.

So I kept my name. And despite the occasional strange looks I got (and sometimes still get) from people who think it odd and despite the awkwardness of making calls on behalf of my children and having to use two different surnames to identify who they were and who I was, I am very glad that I did. Especially now when I see how many women disappeared into thin air historically when they changed their names, I realize how much it can matter to have your own identity, including your own name.

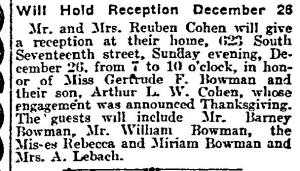

In the case of Jacob and Sarah Cohen’s daughters, I was actually able to figure out their married names, and so they did not disappear into thin air. Sometimes it was really easy to find them because there was an entry in the online marriage records that revealed both the groom’s and bride’s names. Other times it was rather serendipitous.

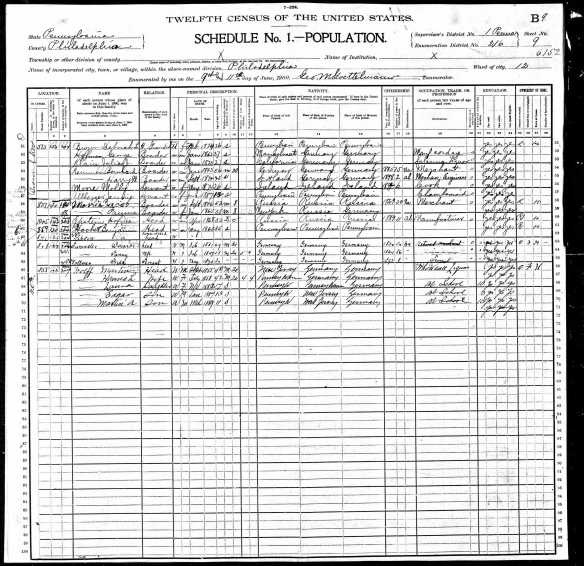

For example, in the case of Hannah Cohen, Jacob and Sarah’s eighth child, it was a tiny little death notice for Hannah’s troubled brother Hart that caught my eye. I wasn’t even researching Hannah at the time, but the death notice made reference to calling hours for Hart being at the home of Mrs. Martin Wolf. I thought that Mrs. Martin Wolf might very well be one of Hart’s many sisters. I searched for Martin Wolf on ancestry.com and FamilySearch, and I found one in Philadelphia on the 1900 census with a wife named Hannah.

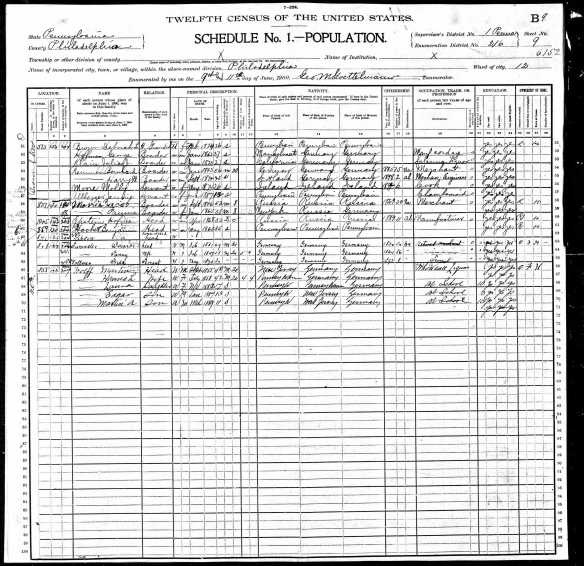

Hannah and Martin Wolf and family 1900 census

According to the 1900 census, Martin and Hannah had been married for 20 years. Hannah’s birth year on the 1900 census was consistent with earlier census reports. Martin and Hannah had three children living with them in 1900: Laura (1882), Edgar (1885), and Martin A. (1889). Martin was in the wholesale liquor business, apparently his family’s business as the city directories list him as working for S. Wolf and Sons, and Martin’s father’s name was Solomon Wolf. It appears that he worked for this business for all or almost all of his adult life.

As I was researching Hannah and Martin’s life, at first it seemed that their life would be like Hannah’s sister Rachel’s life—fairly uneventful. But as I researched more deeply, unfortunately it seemed her life had plenty of unhappy events, though not as overwhelmingly sad as that of her sister Maria.

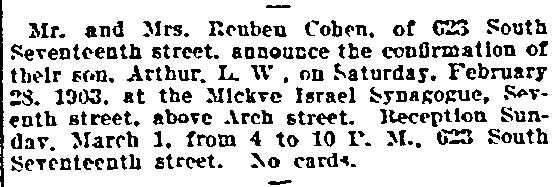

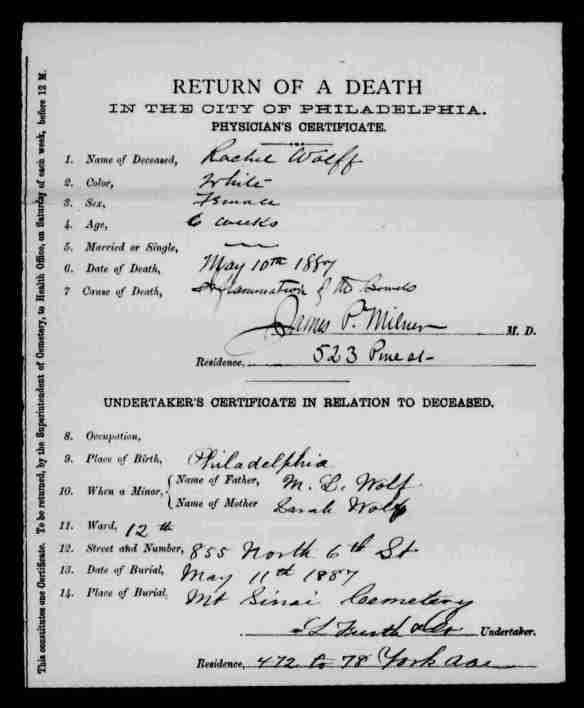

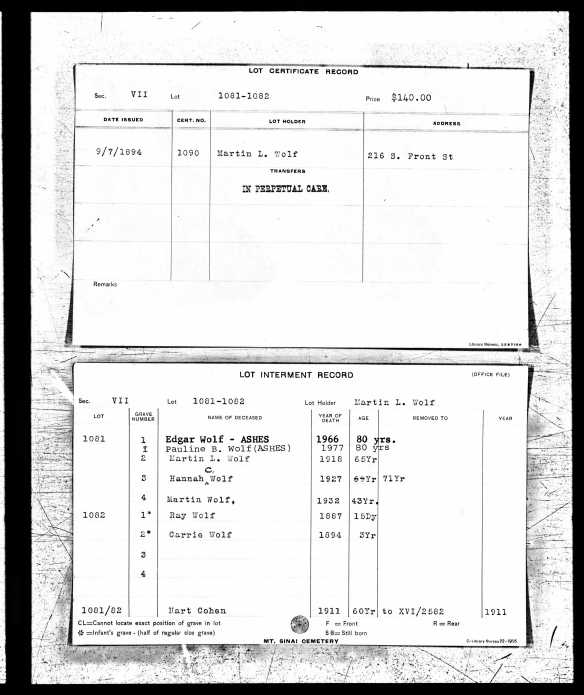

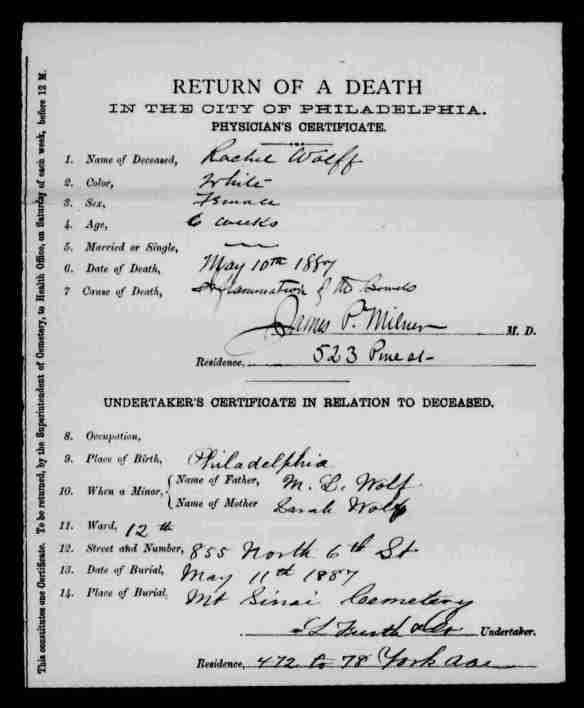

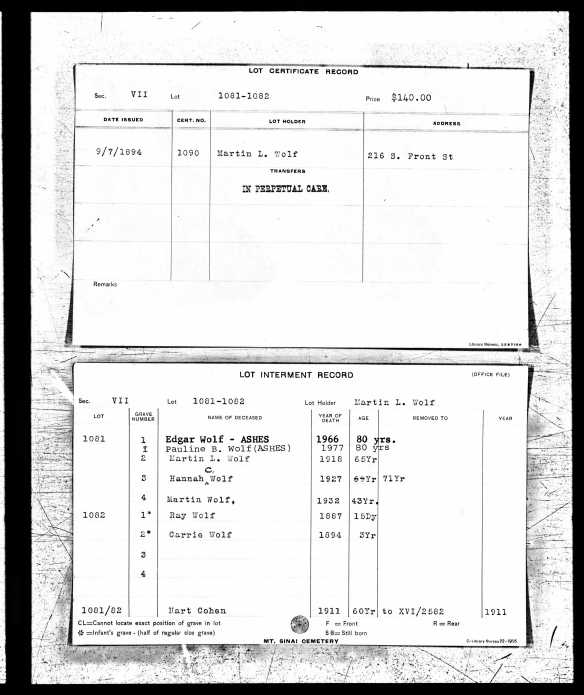

First, I saw on burial records at Mt Sinai that there was an entry for a fifteen day old infant “Ray Wolf” who died in 1887 located in the same lot as Hart Cohen (Hannah’s brother) and other members of the Wolf family. I found a death certificate for a Rachel Wolff who died on May 10, 1887, at six weeks, daughter of M.L. Wolf and Sarah Wolf, living at 855 North 6th Street, the same address in the city directory for Martin L. Wolf of S. Wolf and Son in that year. Despite the error in the mother’s name and the inconsistent age at death, this is obviously the child of Martin and Hannah. Little Rachel died of inflammation of the bowels.

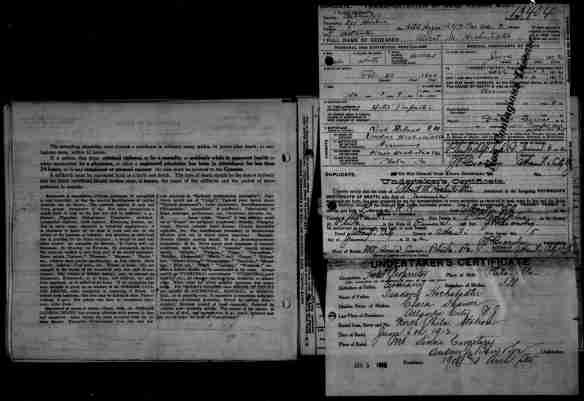

Rachel Wolf death certificate 1887

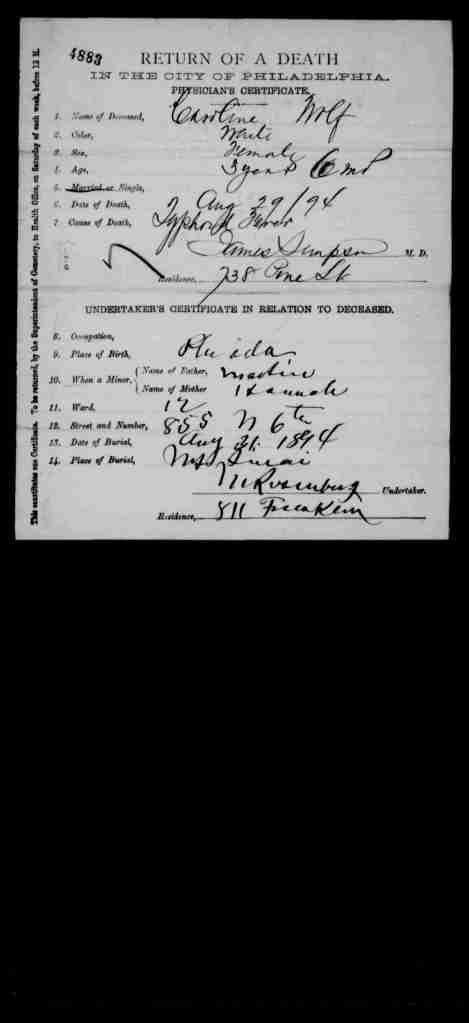

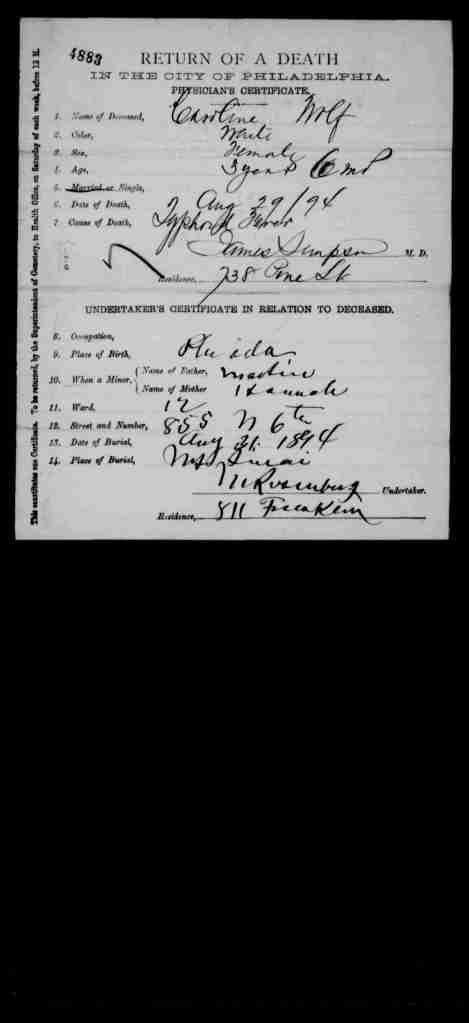

Those same burial records also included an entry for a Carrie Wolf, aged three years, who died in 1894. Once again, further research revealed another terrible loss for Hannah and Martin. Their daughter Caroline died from typhoid fever, the disease that had also killed two of her first cousins, a child of Fanny and Ansel Hamberg and a child of Joseph and Caroline Cohen. If little Caroline was named in honor of her aunt Caroline, that must have been an awful irony to see her niece die from the same disease that had killed their son Hart.

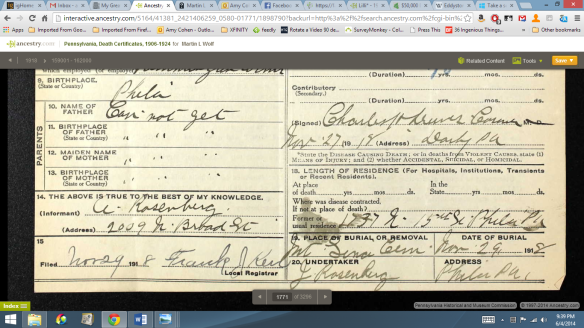

Caroline Wolf death certificate 1894

So between 1887 and 1894, Hannah and Martin had lost two young children. Somehow they continued on, Martin continuing to work in his family’s liquor business and Hannah home with the remaining children, who by 1900 ranged in age from 11 to 17. In 1901 and 1902, the family was living in Atlantic City, where Martin was still involved in the liquor business. Perhaps his family business was expanding, or perhaps the family just needed a change of scenery. Laura, their oldest daughter,married Albert Hochstadter in 1901 when she was nineteen years old. Albert was a hotel proprietor in Atlantic City, so perhaps she had met him while her family was living there. Albert and Laura had a son, Martin Hochstadter, born in 1904.

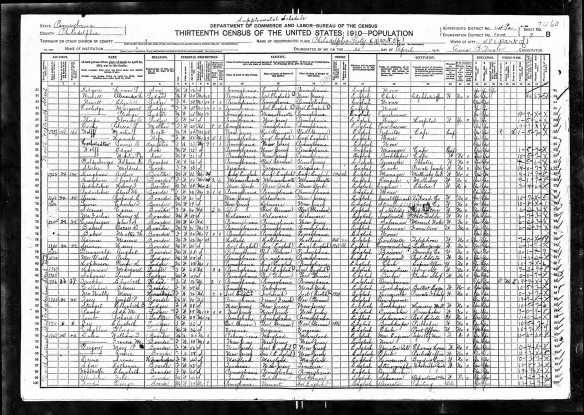

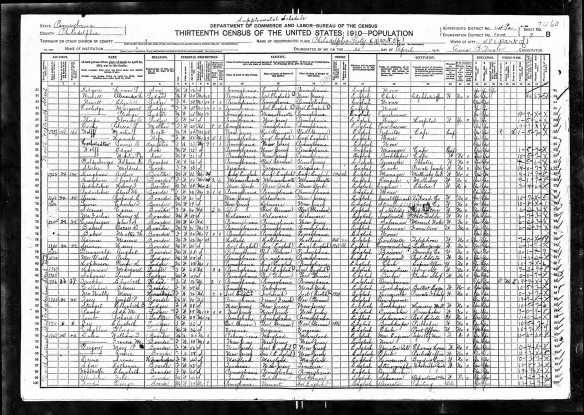

It might have seemed that life had settled down and that the worst was over, but then there were more changes and losses ahead. On the 1910 census, Laura, married only nine years before, was living at home with her parents (who had returned to Philadelphia by 1903) and, according to the census report, widowed.

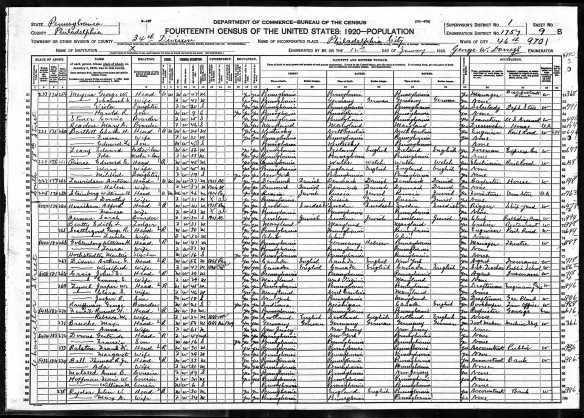

Hannah and Martin Wolf and family 1910 census

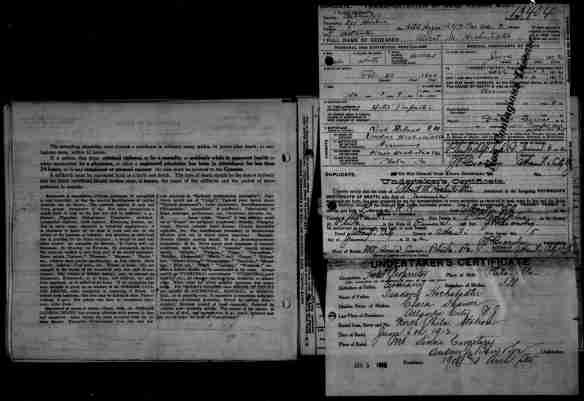

At first I thought, “How awful. Her husband died before they were married ten years,” but I said she was widowed “according to the census report” because I found a death certificate for Albert Hochstadter, dated June 5, 1912. Albert was still alive at the time of the 1910 census when Laura claimed to be a widow. Moreover, his death certificate says that he was divorced. Did Laura lie to the census taker, embarrassed to be divorced, or did the census taker just get it wrong? At any rate, it’s a bit eerie that Albert did in fact die just two years later when he was only 46 years old. His cause of death was reported to be uremia.

Albert Hochstadter death certificate 1912

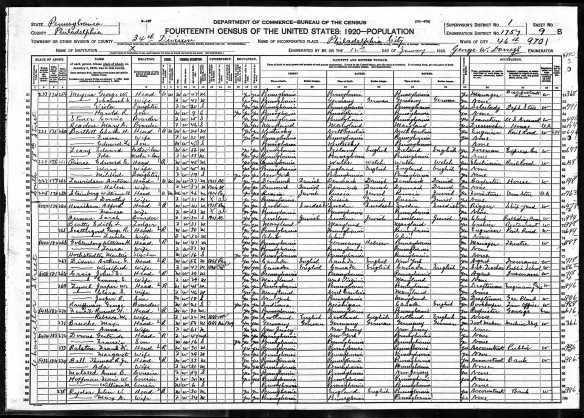

Laura had quickly moved on and was already remarried by the time her first husband Albert had died. On the 1910 census, when Laura was living with her parents in Philadelphia, there was a boarder living there named William K. Goldenberg who was a treasurer for a theater. Within a year, Laura had married William, and by 1920, Laura, William, and Laura’s son Martin Hochstadter were living together. William had advanced to become the manager of the theater, an occupation he continued to hold for many years.

Laura and William Goldenberg 1920 census

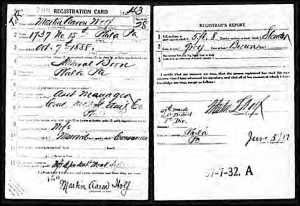

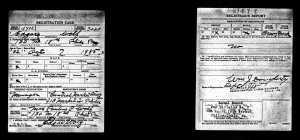

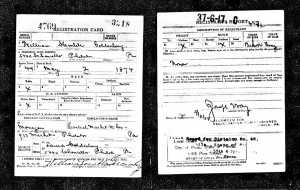

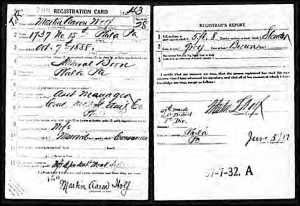

Both of Martin’s sons registered with the draft, and both were employed at the Central Market Street Company at the time of their registration, as was their brother-in-law William Goldenberg. I assume that that was the company that owned the theater where William was the manager. It seems he took good care of his brothers-in-law by providing them with employment.

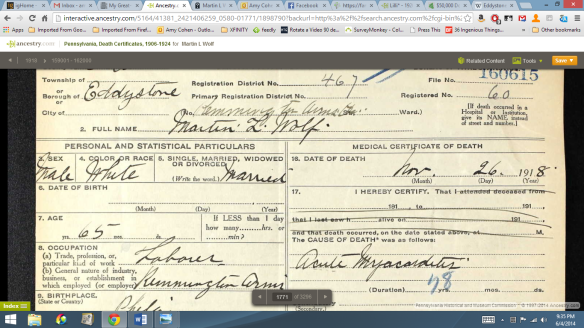

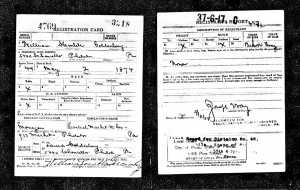

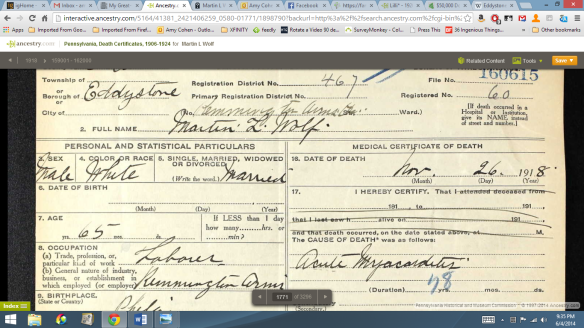

But in 1918 the family suffered another loss. Hannah’s husband Martin died from acute myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart, while in Eddystone, Pennsylvania, which is about 16 miles south of Philadelphia (and once the hometown of Jennifer Aniston, for you trivia fans). The certificate is definitely for the same Martin L. Wolf; it indicates that Martin’s former or usual residence was 1737 North 15th Street in Philadelphia, the same address listed for Martin L. Wolf in the 1918 city directory and in the 1912 directory that also provided his business address for the liquor business.

But the certificate raises some questions. It says that Martin’s occupation was as a laborer for Remmington Arms in Eddystone. According to Wikipedia, Remmington Arms, the rifle manufacturer, had opened a plant there during World War I, and “a large portion of the rifles used by American soldiers in France during World War I were made at Eddystone.” What was Martin doing there? He was 63 years old, too old to be drafted and serve in the war. Was this his way of making a contribution to the war effort? Or perhaps more likely the social forces that eventually succeeded in leading to the 18th Amendment and nationwide prohibition of liquor sales had already led to a decline in Martin’s liquor sales, thus causing him to get a job in the munitions industry during the war. It’s total speculation, but it does seem very strange that after a career in the liquor business Martin would have taken up work in Eddystone making rifles.

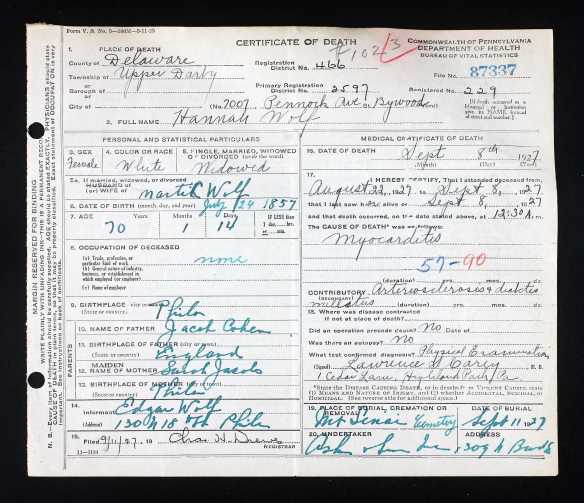

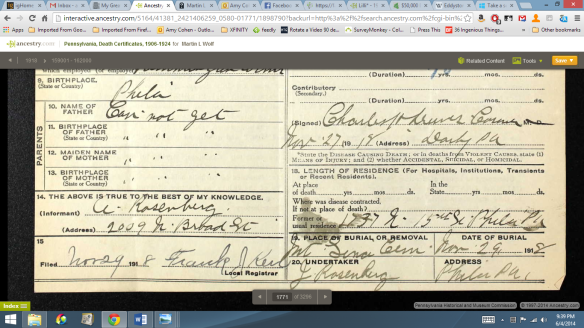

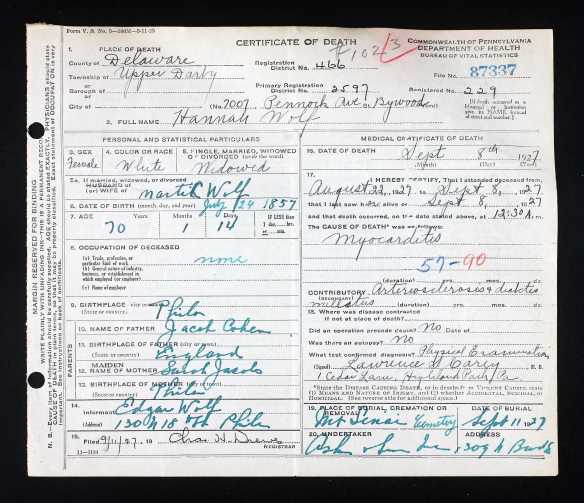

Nine years later in 1927, Hannah also died from myocarditis, arteriosclerosis, and diabetes. She was sixty-nine years old.

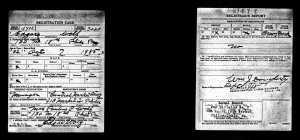

Hannah Cohen Wolf death certificate 1927

She and Martin were both buried at Mt Sinai with their two daughters Caroline and Rachel.

Mt Sinai burial records

In some ways the timing of Hannah’s death may have been a blessing because three years later her daughter Laura died at age 47 from complications of diabetes on February 10, 1930, leaving her husband and her 26 year old son, Martin, who had already lost his father when he was only eight years old.

Laura Wolf Goldenberg death certificate 1930

On the 1930 census Martin was listed as William’s son and had adopted his surname Goldenberg as well. He was also employed as a theater manager, another member of the family finding employment through William Goldenberg. Martin married later that year, and in 1940 he was continuing to work as a theater manager.

William and Martin Goldenberg 1930 census

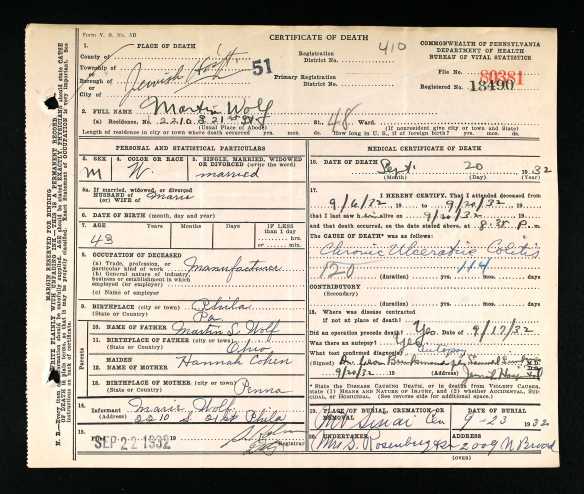

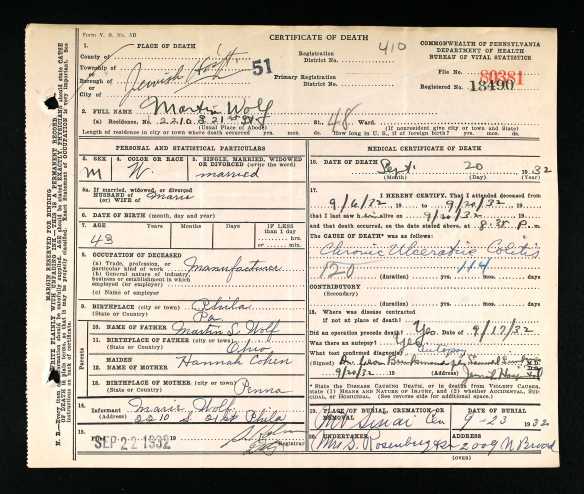

Two years after Laura died, her brother Martin A. Wolf died from chronic ulcerative colitis on September 20, 1932, at age 43. He also left behind a wife and a nine-year old son. Martin A. also had continued to work as a theater manager. His wife Marie died seven years later in 1939, leaving their son Martin without parents at age sixteen. On the 1940 census he was living as a lodger with a couple named Magee and working as an usher, following in the footsteps of his father and other relatives.

Martin A Wolf death certificate 1932

That left Edgar as the only surviving child of the five children of Hannah and Martin Wolf. Edgar had married in 1916 and had had a son in 1921, and like his brother Martin, his brother-in-law William Goldenberg, and his nephews Martin Goldenberg and Martin A. Wolf, he also continued to work as a theater manager in Philadelphia. Edgar died in 1966. He was eighty years old and was the only one of his siblings to live a full and long life. No one else had made it to 50, let alone 80.

When I look back on Hannah’s life, as with the lives of so many of the women I have researched, I realize how completely a woman’s life was defined by her husband and her children in those days. Whereas I can report on the men’s occupations and their military careers, for the women I seem only to be able to mention where they lived, who they married, and how many children they had. Unless a woman remained unmarried, she did not work outside the home. These women had hard times and raised their families under often difficult circumstances, losing babies and children to disease and having more pregnancies and childbirths than I can imagine, and probably even more than are reported. It was the way women lived for most of history: family and home centered and dependent financially on their fathers and then their husbands. It is a very different life from the one most women I know live today, for better in many ways, but also for worse in other ways.

If women’s lives and their value was based primarily on their children, then losing a child must have been especially awful for these mothers, losing two unimaginable. At least Hannah did not live to see that two more of her children would die prematurely. She had lost two babies and her husband. Nine of her siblings, including some younger than she, had predeceased her. Those are enough losses for any person to have to endure.

If I had not found that little death notice mentioning a Mrs. Martin Wolf, Hannah Cohen might never have been found. As you will see, it was an equally serendipitous discovery that allowed me to learn the story of her younger sister Elizabeth. Hannah’s life was a life with plenty of heartbreak. She did not make any scientific discoveries or make a lot of money or change the world. It was nevertheless a life that should not disappear simply because she changed her name when she married or because she never worked outside the home. I am glad that I was able to help to preserve her name and her life for posterity.