When I spoke with Fred Katz, I had many questions about what it was like to come to the US in 1938, a nine year old boy leaving the small town of Jesberg, arriving in New York City, and then settling in Oklahoma. Fred made it seem as though this was not a very difficult adjustment for him, although he said it was harder for his parents. I asked how he felt about leaving Germany, and he said that he had been very excited to come to the US although sad to leave the family’s horse behind. He said he learned English quickly and adjusted easily to school in Oklahoma, and he said the family felt comfortable in Oklahoma, having so many other family members around, most of whom had been either born in or living in the US for quite some time.

So what happened to the rest of the family of Karl and Jettchen Katz after immigrating to America in the late 1930s? What happened to Fred’s two older brothers, Walter and Max?

On September 24, 2000, two graduate students at Wichita State University, Janice Rich and Paul Williams, conducted an oral history interview of Walter Katz. That interview, which remains unpublished, is the source of much of the information in this post.

In the interview Walter spoke about the family’s decision to leave Germany after 1933. He told the interviewers that boys who had been his friends before Hitler came to power ganged up on him and threw dirt clods at him, giving him a black eye; after 1935, his father and uncle were not legally allowed to engage in their cattle trading business, but they persisted illegally at great risk. He also shared the story that Fred had told of the difficulties the family had getting visas from the American consulate and of Fred’s rescue of the Torah scroll after Kristallnacht.

Walter also noted that his uncle Jake in Oklahoma had facilitated Max and Walter’s departure from Germany by submitting affidavits to support their applications for exit visas. When Walter left Germany, he sailed to New York, stayed with relatives there for a few days, and then took a train to St. Louis where he was met by his uncle Jake. Obviously Jake was very instrumental in saving Karl’s family from the Nazis.

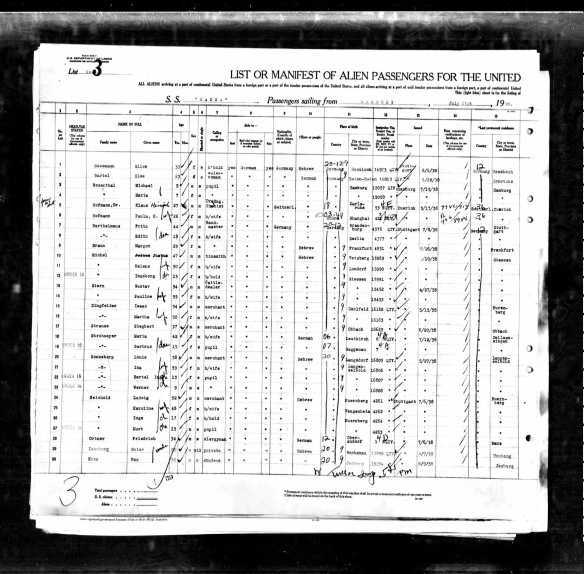

Walter Katz on passenger manifest, line 29, Year: 1937; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Microfilm Roll: Roll 6055; Line: 1; Page Number: 50

Description

Ship or Roll Number : Roll 6055

Source Information

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957

Jake brought him back to Stillwater where he was enrolled in school and was quickly put on the football team (he was seventeen, but because he did not yet know English, he was placed in junior high school).

Walter’s younger brother Max arrived in New York on July 21, 1938, and also listed that he was going to his uncle in Stillwater, Oklahoma:

Max Katz passenger manifest

Year: 1938; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Microfilm Roll: Roll 6188; Line: 1; Page Number: 101

Description

Ship or Roll Number : Roll 6188

Source Information

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957

Finally, Max and Walter’s parents and brother Fred arrived on November 30, 1938:

Karl Katz passenger manifest, Year: 1938; Arrival: New York, New York;Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957;Microfilm Roll: Roll 6258; Line: 1; Page Number: 16

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

In 1939, Walter moved to Wichita, Kansas, where he worked at a men’s clothing store owned by two of his Youngheim cousins. In 1942, he was drafted and inducted into the army at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. He was then transferred to Camp Cook in California (now Vantenberg Air Force Base) and was soon naturalized as a United States citizen, as he described in the oral history interview.

Walter was assigned first to the 5th Armored Division and worked in company supply because of his retail experience. He trained in Tennessee and in New York and was then transferred to intelligence school at Camp Ritchie in Maryland where he received two months of intensive training to prepare him to interrogate POWs. He and 300 other servicemen from his base were then sent to the UK for seven months more of training. After that he was stationed in France, Belgium, and Germany. In France Walter became entangled in the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944; while en route to Paris to pick up jeeps, he learned that the Germans had broken through Allied lines, and his unit, which had been stationed in Reims, France, was relocated to Belgium.

In Germany Walter was part of the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) where his job after the war was to interview and arrest civilian officials who had been Nazis and to see that they were replaced with those who had not been affiliated with the Nazis. Walter told his interviewers that the people he interviewed all denied being Nazis and claimed they had no choice but to follow orders.

While in Germany, Walter met up with his cousin Jack Katz, Aron’s son, who was stationed in Wiesbaden. The two cousins attended high holiday services in 1945 at a restored synagogue in Bad Nauheim. In one of those eerie small world stories, a teenage boy who participated in the service later married one of Walter’s cousins. Walter did not know of this coincidence until visiting that cousin in New York years later.

Walter and Jack also visited Jesberg while they were stationed in Germany. Walter was distressed by the state of the cemetery, which had been vandalized during the war, and he demanded that the mayor restore the stones that had been toppled and clean up the damage, which was done by the next time he visited. Walter and Jack also met a young Jewish woman they’d known in Jesberg who had been in one of the camps and wanted to live in Jesberg again. She had no money, so Walter went to the man who had been the local Nazi official responsible for the damage to the synagogues and Jewish homes and businesses and demanded that this woman be provided with everything she needed.

Walter and Jack visiting the former Jesberg synagogue after World War II, courtesy of the Katz family

Although Walter had an opportunity to stay in Germany and work for the State Department, he wanted to return to the US. He returned to Wichita and to his work in his cousin’s men’s clothing store, The Hub, which he eventually purchased. He married his wife Barbara Matassarin in Denver on July 7, 1950. Barbara had been a nurse training in Wichita when she met Walter and had enlisted in the US Army as a second lieutenant in early 1950. When she was assigned to a hospital in Denver, they decided to get married. Walter and Barbara lived, however, in Wichita with their daughter for most of the rest of their lives, and Walter remained in the men’s clothing business until he retired.

Walter’s brother Max also served in the US army during World War II. He served in the Army Air Corps from 1942 until 1945, according to his obituary. Like Walter, he became a US citizen while serving in the armed forces. According to his brother Fred, Max was stationed stateside during the war and did not fight overseas.

After the war, Max returned to Oklahoma and attended Oklahoma A&M for two years, receiving a certificate in business. He worked in the meat packing industry for several years before starting his own cattle trading business in 1953.

According to his obituary, “in 1973, Max began buying pasture land throughout Payne County and feeding his own cattle, in addition to commission buying. At any given time, Max usually had about 3,000 head of cattle either on pasture or in feed lots. Max retired from the cattle business in 2009.” Tulsa World, January 1, 2011.

Walter, Max, and Fred Katz lost their father Karl in 1966 and their mother Jettchen in 1979. Both had remained in Stillwater, where they are buried.

Walter Katz died in Israel on November 5, 2007; his wife Barbara had predeceased him on July 1, 2000. They are buried in Israel. Max Katz died in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on December 30, 2010; he is buried in Stillwater.

According to his obituary, Max Katz “was known far and wide as a superior cattle buyer and rancher who created a successful 56-year career in the cattle business by relying on a keen eye, a razor-sharp business sense, honest dealings, and above all, pure hard work. His generosity and willingness to help others in need became his hallmark and reputation.” Tulsa World, January 1, 2011.

Walter Katz, when asked in 2000 by his interviewers what he would say to the youth of America, said “First, you are lucky to be born in the United States. Second of all, you can do anything here that you want to do if you put your mind to it. The opportunity for anything you want to do is here if you want to do it. Work hard and stay with it and be good and honest. Live a good honest life and you will make it!”

Although those words do not necessarily reflect the experiences of everyone in this country, they do reflect the experiences and the values of Walter Katz and of his brother Max. Both Walter and Max had escaped from Germany as teenagers and traveled by themselves to the United States; they both had contributed greatly to their adopted country. They served in its military during a war against their country of birth, and they worked hard to become successful businessmen.

And yet these were two men who almost did not get into this country because of some bureaucrats dealing with immigration in the 1930s. How many more could have been saved? How many more were turned away because of ignorance, fear, and prejudice? Will we ever learn?