With more realistic expectations but nevertheless high hopes, I awaited Ava’s final work on the Nusbaum Album, some of the photographs from Germany. Although there were some photographs from Stuttgart, Berlin, and Wiesbaden, since I did not know of any relatives living in those places in the mid to late 19th century, I focused on the photographs taken in Bingen and Mainz. Although my closest Seligmann relatives lived in the small town of Gau-Algesheim, both Bingen and Mainz were relatively close by and the closest cities to Gau-Algesheim, and many relatives eventually moved there. It seemed most likely that that my Seligmann relatives would have gone to one of those two cities to be photographed.

I selected three photographs from Mainz, all taken by the same photographer, Carl Hertel, and two from Bingen, both taken by J.B. Hilsdorf. These were all on the back of the first four pages at the beginning of the album whereas other photographs from Germany including from Mainz and Bingen were much later in the album. I hoped that meant the ones earlier in the album were more likely closer relatives.

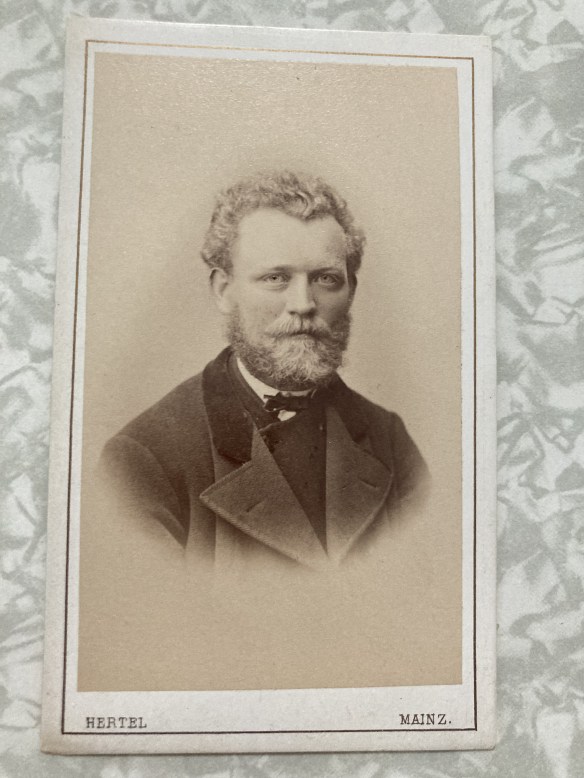

The first Mainz photograph was dated by Ava as taken between 1873 and 1874; she noted that in 1874, Hertel became a court photographer. She wrote, “Generally, when a photographer was appointed as a court photographer that information would appear on the mounting card in the imprint and after the photographer’s name with the letters HOF. Since there is no indication of this appointment, I am placing the date of the photograph before 1874.”1 In addition, another photograph of Hertel’s found elsewhere with the same imprint was dated 1873.

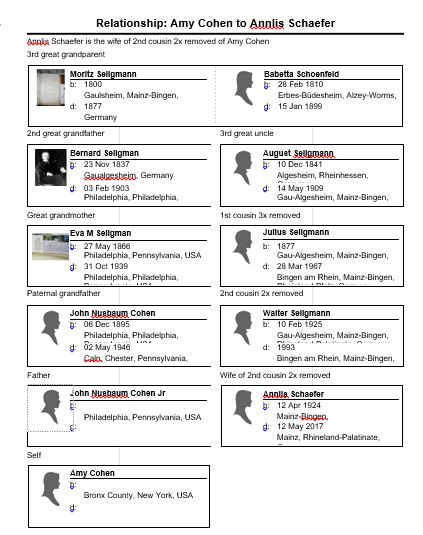

Ava estimated the age of the man as mid to late 70s based on the lines on his face and the style of his tie. That meant the man was born in about 1800-1804. Ava speculated that this could be my three-times great-grandfather Moritz Seligmann, who was born in 1800. And this time I was able to confirm that speculation because I belatedly remembered that I have an actual photograph of Moritz that I had obtained from a cousin years back:

So bingo! We had a positive identification!

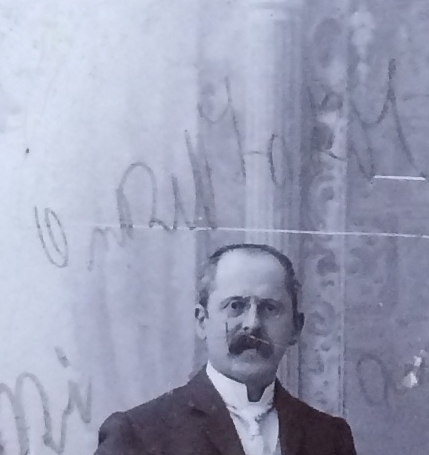

Moving on to the next two Mainz photos, Ava concluded that they also were taken between 1873 and 1874 based on the information she’d already found about Hertel. The first one she believed to be of a man who was in his thirties, perhaps 35, so born in about 1838-1839. The younger man on that same page appeared to her to be eighteen so born in about 1855. Since these photographs were all taken by the same photographer at about the same time, I thought that perhaps these two younger men were sons of Moritz Seligmann, that is, brothers of Bernard, my great-great-grandfather. In addition, they appeared on the second page of Germany photographs right after the photograph of Moritz, who appeared on the first page of the Germany photographs in the album.

Looking at the family tree, I found two possibilities. The older “son” could be Hieronymous Seligmann, born in 1839. The younger “son” could be Moritz’s youngest child, Jakob Seligmann, born in 1853. I was excited at the thought that perhaps I finally had found some relatives I could identify in the album.

I shared my analysis with Ava. She was skeptical that the younger man was Jakob Seligmann because she had identified Jakob in a photograph from a different set of photographs that she had worked on during an earlier project, and she did not see any similarities or enough to believe that the blonde teenager photographed in Mainz was the same person identified as Onkle Jakob in the later photograph.

We went back and forth with me trying my lawyerly best to persuade her that the blonde man could have grown up to be the dark haired Oncle Jakob. But in the end I failed to do so. I have to defer to Ava. She’s the expert, and I am a biased viewer hoping to see what I want to see. But if this was not Jakob Seligmann, who was it? I don’t know. Maybe a nephew or a cousin. Maybe not anyone in the family at all.

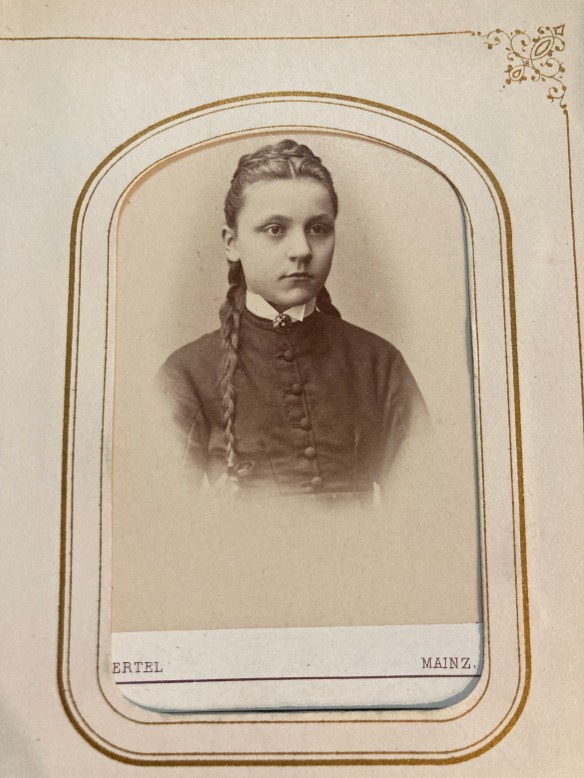

Knowing now that the Hertel photographs were likely taken before 1874 as Ava concluded, I looked on my own at the other three Hertel photographs taken in Mainz that appear later in the album:

Who are these three women? I don’t know since I have no photographs to use for comparison. Two of them look too young to be Bernard Seligman’s sisters Mathilde and Pauline, who were born in 1845 and 1847, respectively, and certainly too young to be his half-sister Caroline born in 1833, if the photographs were taken around 1873 as Ava concluded about the other Hertel photographs. And they are too old looking to be the children of any of Bernard’s siblings. So sadly they also will remain unidentified.

Who are these three women? I don’t know since I have no photographs to use for comparison. Two of them look too young to be Bernard Seligman’s sisters Mathilde and Pauline, who were born in 1845 and 1847, respectively, and certainly too young to be his half-sister Caroline born in 1833, if the photographs were taken around 1873 as Ava concluded about the other Hertel photographs. And they are too old looking to be the children of any of Bernard’s siblings. So sadly they also will remain unidentified.

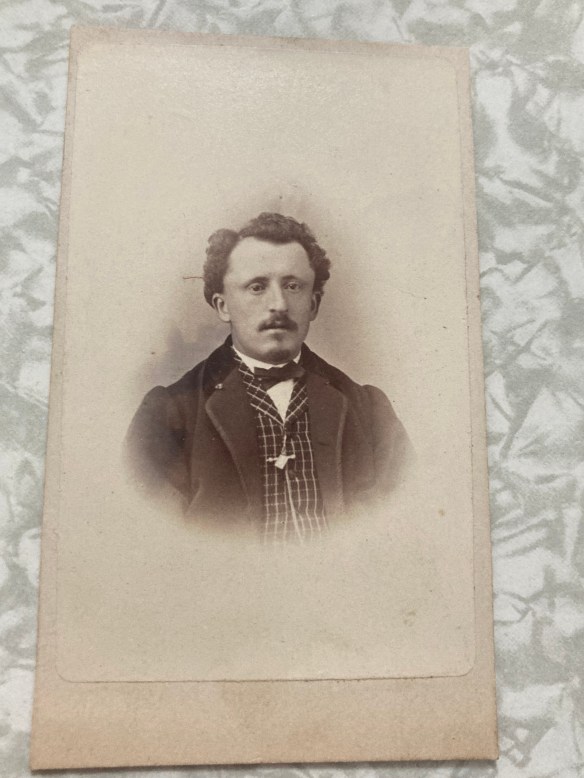

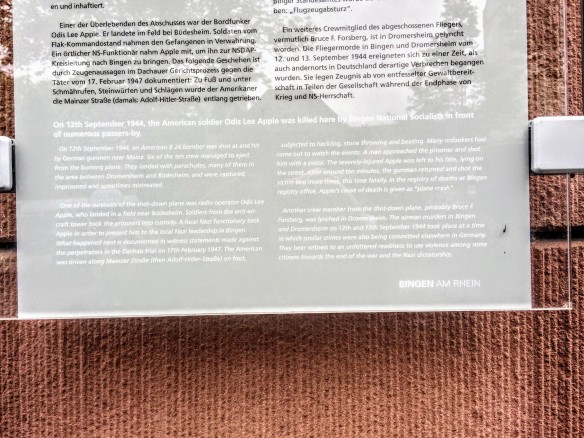

The next photograph I asked Ava to analyze is on the same page as the two blonde men except this photograph was taken in Bingen, not Mainz, by J.B. Hilsdorf, who was in business in Bingen from 1861 to 1891, according to Ava’s research. When I believed that the other two men on that page were Hieronymous and Jakob, I speculated that this third man could be their brother August, the only other son of Moritz Seligmann who survived beyond 1853 and was living in Germany.

Based on the size of this particular photograph, Ava dated it in the mid-1860s. She thought the man was between 30 and 35 so born between 1827 and 1834.2 August Seligmann was born in 1841 so too young to be the man in this photograph. In addition, Ava compared this photograph to one I have of August and found them to be dissimilar. It didn’t take as much to persuade me this time.

That left one last photograph for Ava to analyze, the second photograph from Bingen that I had selected.

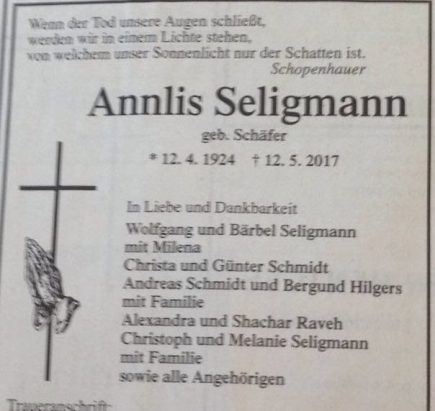

It also was taken by J.B. Hilsdorf, and for the same reasons Ava dated it in the mid-1860s. She estimated the woman’s age to be in her late 40s, early 50s, giving her a birth year range of 1812 to 1817. Based on the age and other photographs I have of my three-times great-grandmother Babette Schoenfeld Seligmann, Ava thought there was a good possibility that this photograph was also Babette. Here are the other photographs of Babette that Ava used for comparison.

Ava did an incredible job of researching the photographers and the photographs they’ve taken to come up with reliable time frames for when the album photographs were likely taken. But it is only possible to go so far with identification without known photographs of the people in your family to use for comparison. You can narrow down the possibilities and eliminate those who clearly do not fit within the parameters of the dates, but you can never be 100% confident of the specific identity of the person in the photograph based just on dates and locations. I wish I had more photographs that Ava could have used to make facial comparisons, but I don’t. I have to accept that I may never know who most of these people were.

Fortunately, there were a handful of photographs in the Nusbaum Album that were labeled and that I could on my own identify and place in my family tree. More on those in my next few posts.