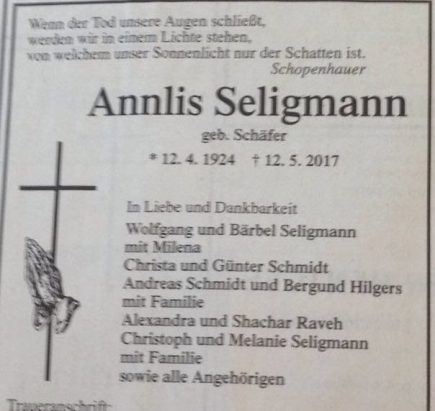

On our second night in Germany (May 3), we had a truly joyful and unforgettable experience: dinner with Wolfgang and his family—his wife Bärbel and their twelve year old daughter Milena. We met in the small town of Schwabenheim, located about halfway between Bingen, where we were staying, and Undenheim, where Wolfgang and his family live. I could not remember the name of the restaurant, but fortunately I was able to WhatsApp with Milena who told me it was zum Engel. The atmosphere was perfect—an old stone building divided into smaller rooms with just a few tables. It was a good thing that for much of the time we had our room to ourselves because there was much laughter throughout our meal.

All three Seligmanns understand English, but I wanted to practice my German. So we switched back and forth, often with many questions about which word to use (on my part) and some inevitable misunderstandings based on use of the incorrect word (again, on my part). It could not have been a more enjoyable and relaxing evening—remarkable given that I’d never met Milena or Bärbel before and had only met Wolfgang the day before. The food was also excellent—salmon, potatoes, and my first experience with the white asparagus that is so popular in Germany—“spargel.” Es war lecker, as they say. When Wolfgang asked at the end of the evening whether we wanted to have dinner with them all the next night, there was no hesitation. “Of course,” we said. (I think the German equivalent expression is “genau”—a word we heard over and over when we listed to Germans converse with each other.)

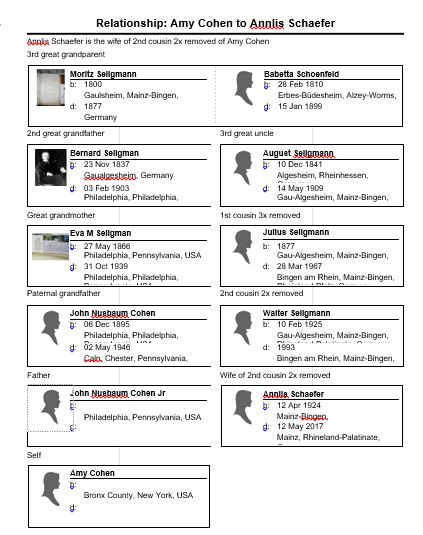

The following day Wolfgang, Harvey, and I traveled to Gau-Algesheim, the birthplace of my great-great-grandfather, Bernard Seligman, and of his younger brother August Seligmann, Wolfgang’s great-grandfather. But first Wolfgang took us to see the Rochus Chapel outside of Bingen where his grandparents and father and uncle hid during the bombing of Bingen during World War II. It is lovely church perched high above Bingen surrounded by trees and views of the valley and of the Rhine. It was easy to see how this must have been a peaceful sanctuary for Wolfgang’s family and others during the bombing.

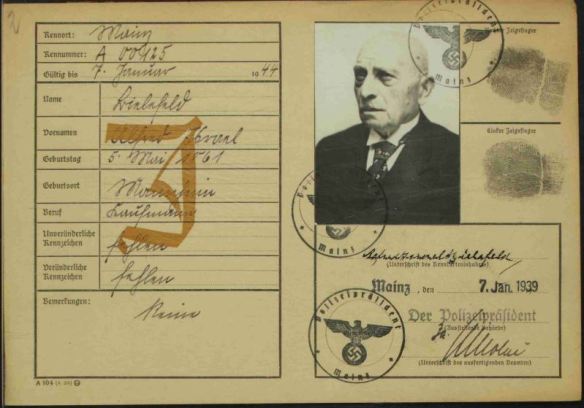

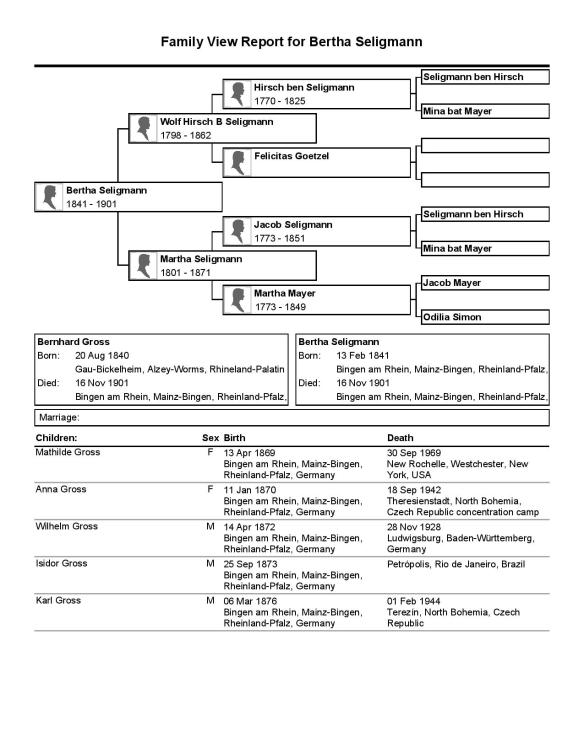

In some ways the survival of Wolfgang’s grandfather, father, and uncle is a miracle. Julius Seligmann was born Jewish, but converted when he married Magdalena Kleisinger, who was Catholic. Their sons, Walter and Herbert, were raised as Catholics. But in Nazi doctrine, that should not have mattered. Julius had “Jewish blood,” and so did his sons. Many of those with Jewish ancestors who converted or who were raised as Christians were not spared from death by the Nazis.

When I asked Wolfgang why he thought his grandfather, father, and uncle survived, he said that his mother always said that the Bingen Nazis were stupid. Or that perhaps the police in Bingen somehow provided protection. As I wrote earlier, Wolfgang’s father Walter did forced labor on the Siegfried Line during the war and there were restrictions placed on the men in terms of their occupations, but they were not deported or tortured. I am thankful for that; otherwise, my dear cousins Wolfgang, Bärbel, and Milena would not be part of my life.

After leaving Rochus Chapel, we drove the short distance to Gau-Algesheim where we were to meet Dorothee Lottmann-Kaeseler, another German dedicated to preserving and honoring the history of the Jews in Germany. Dorothee and I had connected several years back through JewishGen.org when I was searching for information about Gau-Algesheim. She had worked on a cemetery restoration project with Walter Nathan, a man whose father’s roots were in Gau-Algesheim; Walter and his family had escaped to the US in 1936. Dorothee and I have been exchanging information through email for several years—going far beyond my initial inquiries about Gau-Algesheim, and she is a regular reader and frequent commenter on my blog. I was very much looking forward to meeting this friend in person, and she is terrific—outgoing, energetic, interesting, smart, and very insightful.

But it took some chasing to catch her! We drove up the road below the cemetery, and Wolfgang spotted what he believed was her car up on the hill near the cemetery gate. We got out of the car and clambered up the hill only to see that Dorothee’s car had disappeared. (We were a few minutes late arriving.) So we ran back down the hill, got in Wolfgang’s car, and raced back down the road where we again spotted Dorothee’s car. She had driven back down, thinking we might have missed her. It was like a scene out of a bad romantic comedy!

Anyway, after introductions were made and hugs exchanged, we all drove back up to the cemetery gate. Dorothee was accompanied by a Gau-Algesheim resident named Manfred Wantzen, who had the key to the cemetery. But before we entered, Dorothee reminded us that in fact there were very few stones in the cemetery. This was not an act of Nazi destruction; this was an act of stupidity on the part of a man in the 1983 who may have had good intentions. He thought the cemetery needed to be cleaned up and asked permission of the Jewish community in Mainz (which oversees the cemetery). They agreed without asking what he planned to do. The man then proceeded to remove the stones so he could cut the grass. Some he placed against the cemetery wall, but others were carted away and lost forever.

When Dorothee and Walter Nathan worked to preserve what was left of the cemetery, several plaques and markers were placed on the wall outside and inside the cemetery, one to commemorate those who were killed in the Holocaust and others to honor the memory of those who were buried in the cemetery but whose stones were no longer there.

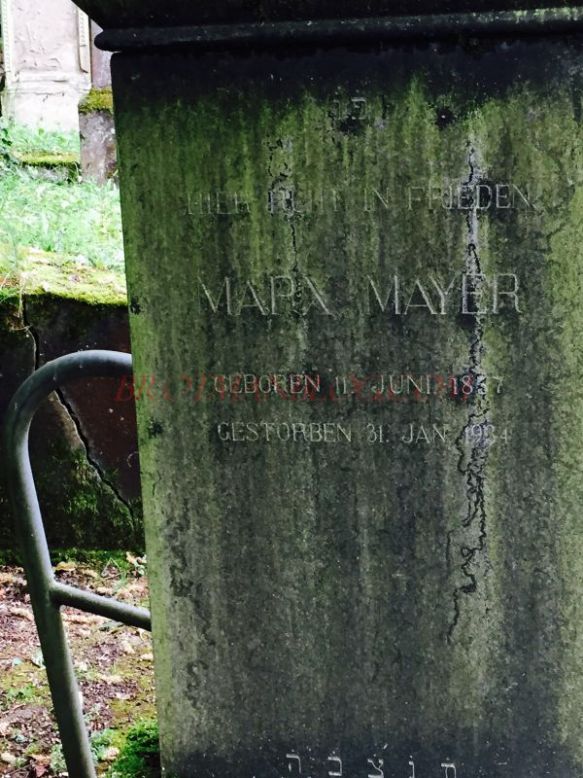

Unfortunately, there were no stones to be found for my 3-x great-grandparents, Moritz Seligmann and Babetta Schoenfeld, who were undoubtedly buried in that cemetery. There were likely many other relatives buried there, including Wolfgang’s great-grandfather August Seligmann, but the only family member whose stone survived is that of Rosa Bergmann Seligmann, August’s wife and Wolfgang’s great-grandmother. But even that discovery was bittersweet as her stone had been vandalized several years ago by some local teenagers. Wolfgang and I each placed a stone on her grave to mark that we had been there and to honor her and all the other Seligmanns buried there.

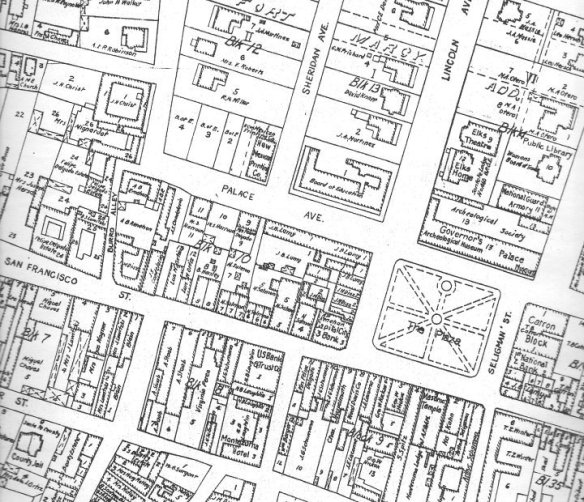

Although I left the cemetery disappointed and somewhat disheartened, my spirits were lifted when we drove into Gau-Algesheim and I got to see this little town of 7000 people where my ancestors had once lived. I have written before about Gau-Algesheim and seen photographs, but it was an entirely different experience being there in person and imagining a young Bernard Seligmann running through the narrow streets into the main square of the town where Langstrasse and Flosserstrasse meet and where the town hall and the fountain are located. Here is Wolfgang standing where perhaps our mutual ancestors Moritz and Babetta once stood with their children:

Dorothee had arranged for us to meet with the mayor of Gau-Algesheim, Dieter Faust. We sat in his office where everyone but Harvey and I spoke rapid German. I tried to understand, but it was futile. The mayor was extremely engaging and clearly excited to have two descendants of Gau-Algesheim residents visiting, and after signing his guest book and taking photographs, we all went to lunch—in an Italian restaurant in the middle of this small German town. And it was excellent! Somehow we all managed to converse and even managed to discuss American, French, and German politics with Dorothee and Wolfgang acting as interpreters. It was a delightful experience.

Burgermeister Dieter Faust, Dorothee Lottman-Kaeseler, Wolfgang Seligmann, Manfred Wantzen, me, and Harvey

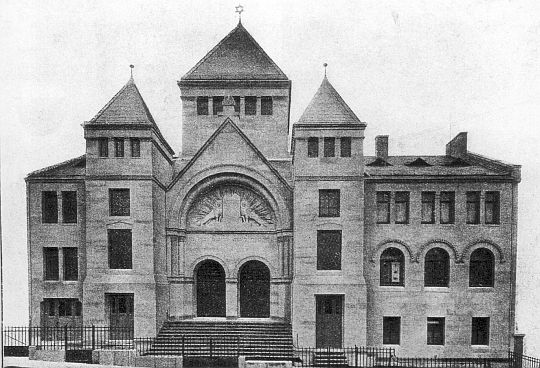

After lunch, Herr Wantzen and Dorothee guided us through the small town where we saw what had once been the synagogue in Gau-Algesheim. It closed before 1932 because there was no longer a Jewish community in Gau-Algesheim. Today it is a storage shed behind someone’s house. But the stained glass window over the door and the windows convey that this was once a house of prayer. A shul where my ancestors prayed almost 200 years ago. It was awful to see its current condition, and I wish there was some way to create a fund to protect and restore the building before it deteriorates any further. I am hoping I can figure that out.

We walked then along the streets where my family had once lived, saw the building where Wolfgang’s grandfather Julius once had a shop, and the street where my great-great-grandfather Bernard and his siblings were born. It was surreal. And emotionally exhausting.

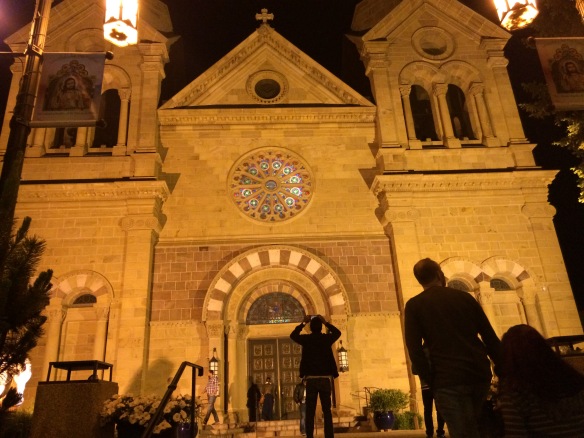

Our last stop was the Catholic Church in Gau-Algesheim, which Herr Wantzen was very excited to show us. It was beautiful—far larger and more elaborate than one might expect in such a small town. And a striking contrast to the size and condition of the abandoned synagogue.

We said goodbye to Dorothee and Herr Wantzen and returned to our hotel for a rest, and then at 6, Wolfgang picked up us again for dinner with his family in Bingen. We went to another very good restaurant, Alten Wache, and again had a wonderful time.

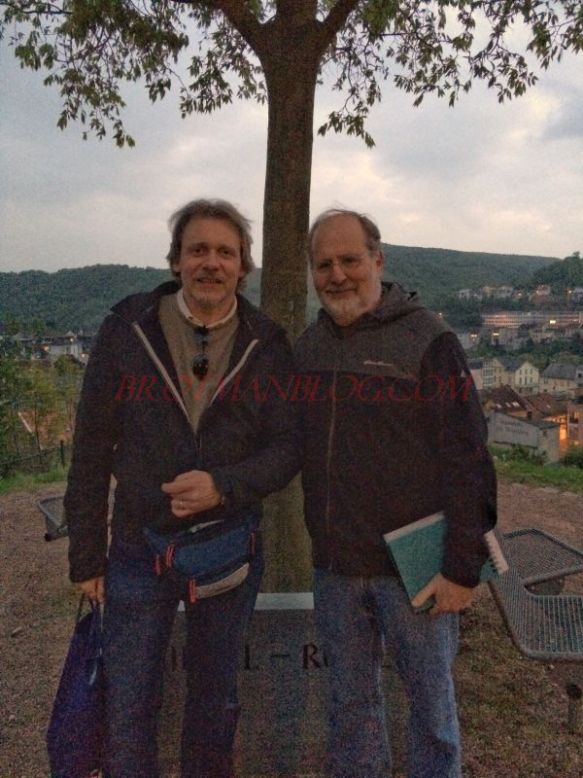

After dinner we all climbed up the many steps to the Burg Klopp, the medieval castle that sits at the top of the hill overlooking Bingen. As the sun began to set, the views were awe-inspiring. But I was already starting to feel emotional about saying goodbye to my wonderful cousins, Wolfgang, Bärbel, and Milena. When Milena said to me in her perfect English that she was going to miss me, my eyes filled with tears.

It was very hard to say goodbye, but I know that I will see my Seligmann cousins again—somewhere, sometime. And until then, we have WhatsApp, email, and all our wonderful memories. Auf wiedersehen, Wolfgang, Bärbel, Milena—and Bingen, Gau-Algesheim, and Mainz. It was time to move on the next step of our journey.

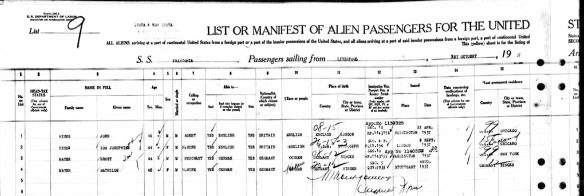

![Paul Lichter on 1938 ship manifest to NY Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Microfilm Publication T715, 8892 rolls. NAI: 300346. Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service; National Archives at Washington, D.C. Supplemental Manifests of Alien Passengers and Crew Members Who Arrived on Vessels at New York, New York, Who Were Inspected for Admission, and Related Index, compiled 1887-1952.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/paul-lichter-ship-manifest-1938-p-2.jpg?w=584&h=589)

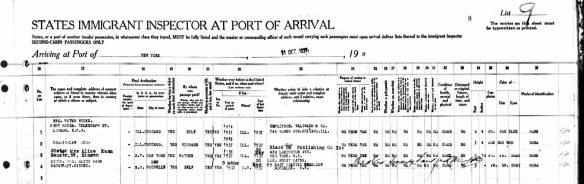

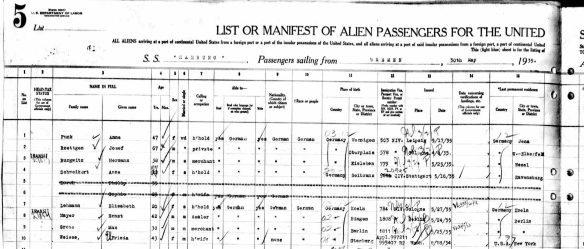

![Renate Lichter on 1939 ship manifest, line 13 Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Microfilm Publication T715, 8892 rolls. NAI: 300346. Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service; National Archives at Washington, D.C. Supplemental Manifests of Alien Passengers and Crew Members Who Arrived on Vessels at New York, New York, Who Were Inspected for Admission, and Related Index, compiled 1887-1952.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/renate-lichter-1939-ship-manifest-line-13-p-2.jpg?w=584&h=580)

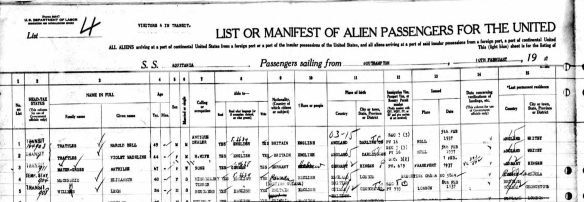

![Paul, Marie, and Lore Lichter on 1940 ship manifest, lines 13-15 Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C. Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Microfilm Publication T715, 8892 rolls. NAI: 300346](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/paul-lichter-and-family-on-1940-manifest-lines-13-14-15-p-2.jpg?w=584&h=629)

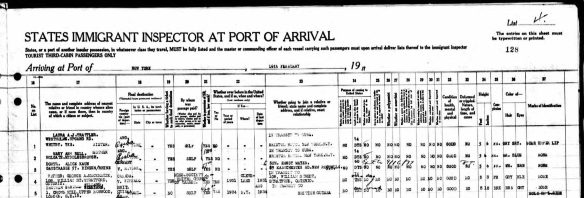

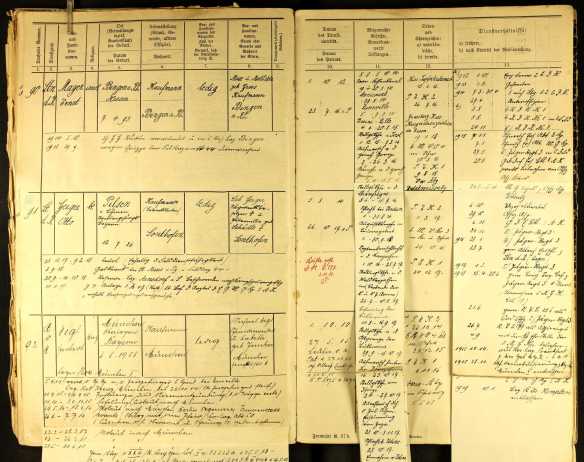

![Paul, Marie, and Lore Lichter on the 1940 UK ship manifest Ancestry.com. UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012. Original data: Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Outwards Passenger Lists. BT27. Records of the Commercial, Companies, Labour, Railways and Statistics Departments. Records of the Board of Trade and of successor and related bodies. The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, England.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/paul-lichter-and-family-on-1940-uk-manifest.jpg?w=584&h=817)

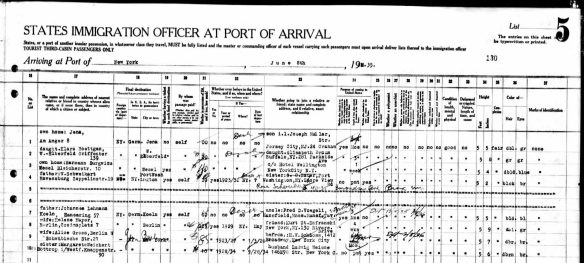

![Ernst Mayer and family passenger manifest August 11, 1936 Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/ernst-mayer-and-family-august-1936-manifest-p-2.jpg?w=584&h=619)