On Friday, May 5, our fourth day in Germany, we left the Mainz-Bingen region behind and took a three hour cruise on the Rhine from Bingen to Koblenz. The weather was still quite dreary and cool, but the views out the window was nevertheless quite scenic—castles, little towns clustered at the shoreline, high cliffs and fields, and other boats cruising on the river. It was very peaceful and relaxing, just what we needed after several very full and exciting days.

We disembarked in Koblenz and walked through that city for an hour or so before taking a train to our next major stop, Cologne or Köln, as it is called in German.

Once we got to the Cologne train station, we realized we had no idea how far our hotel was, so we checked Google Maps on my phone and were delighted to see that our hotel, the Marriott, was just a short few blocks away. Although the Marriott is a large, American-style hotel, we were not very pleased with it. I won’t get into details here, but if anyone is planning a trip to Cologne, check with us first. The best thing about it was its location. We should not have “played it safe” and chosen a known brand. Live and learn.

Nevertheless, we very much enjoyed the two days we had in Cologne. The first night we had dinner at a very chic Italian restaurant, Da Damiano. It wasn’t far from the hotel, but somehow we got a bit twisted around looking for it. But that gave us our first glimpse of the Dom, the huge Gothic cathedral that dominates everything in Cologne. The Dom dwarfs all the churches we’d seen before and even cathedrals we had seen in other cities such as Milan and Paris. It is awesome in the literal sense of the word. And you can see its spires almost anywhere in the city.

The following morning we went to the Ludwig Museum, which is almost right behind the Dom. (The Dom quickly became our point of orientation for anything in the city.) The Ludwig is an extremely well-planned museum with lots of light and open space and a very impressive and enjoyable collection of 20th century art. There were many works by Picasso including a very provocative sculpture of a mother pushing a child in a stroller, a rich collection of Expressionist and Surrealist artists, and a collection of art that had been rescued by a collector during the 1930s when Hitler condemned all modern art as degenerate and corrupt.

But the piece that really took us aback was a lifelike sculpture of a modern-dressed woman staring at art in one of the galleries. Both of us had at first thought it was an actual person and only realized it was a sculpture on a second or third look. It really made us think about what is art and what is real and how we often walk by real people without realizing they are real.

Woman with a Purse, Sculpture, by Duane Hanson (1974) at Ludwig Museum, Cologne, Germany Photo found on Pinterest at https://www.pinterest.com/pin/26317979044298519/

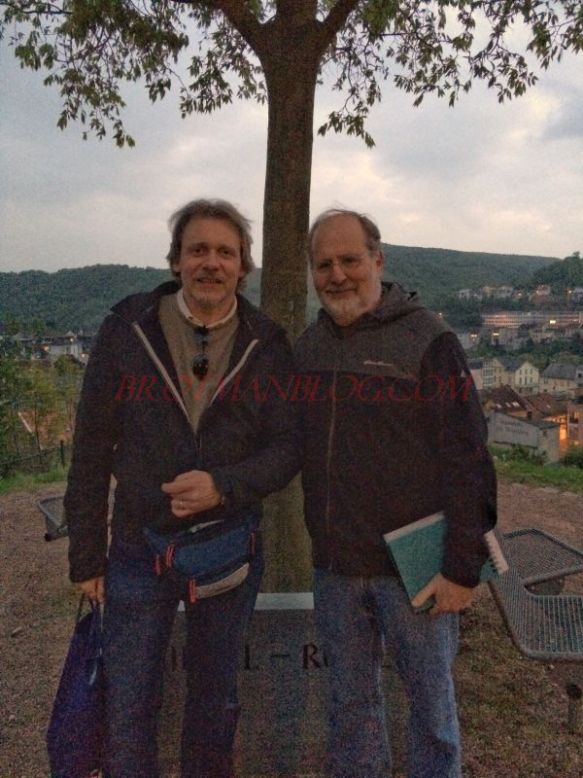

In the afternoon we went on a walking tour of Cologne with Free Walk Cologne (there is no fee, but tips are encouraged early and often). Julian, our tour guide, was fluent in English and very engaging, knowledgeable, and entertaining. We met at the Eigenstein Tur, one of the old Roman gates that still exist in the city, and our group was made up of people from Switzerland, Poland, Ecuador, and Scotland, as well as Philadelphia and California. Julian provided us with some background in Cologne’s long history—it was once a military garrison during the Roman Empire, and a woman from Cologne married the Emperor and made Cologne an important outpost in the empire. Julian claimed that Cologne still had more of an Italian feel to it—more laidback and liberal than most of Germany.

We also learned that one of the reasons Cologne has such a tremendous cathedral is that the remains of the Three Kings are kept there. That made Cologne a pilgrimage destination long ago and thus a wealthy city filled even in early times with constant visitors.

The symbol of Cologne —the three crowns for the Three Kings and eleven tears for the eleven virgins killed by Attila the Hun

Julian then skipped to modern times and informed us that over 90% of Cologne had been destroyed by Allied bombing in World War II and that the city was rebuilt as cheaply and quickly as possible after the war, leaving it with buildings that are eclectic in style and not very well-planned. People were allowed to build whatever they wanted, including a building that is only two meters wide.

Many immigrants from Greece and Turkey came to Cologne after the war to do this rebuilding as the male population of Cologne had been greatly reduced by wartime casualties. These immigrants stayed, giving Cologne a diversity that was for a long time unusual for Germany. (Now there are many immigrants living in Germany from all over the world.)

We saw a church, St Maria Himmelfahrt, that was bombed during the war and restored afterwards:

Perhaps the most bizarre thing we saw was a Roman wall that was discovered in recent years during excavation for a parking lot near the Dom. The wall was preserved and now can be seen in the middle of a modern parking lot.

There was also a Roman floor mosaic discovered nearby, and that also can be seen today by looking into the window of the city’s archaeological museum.

Our last major stop with Julian was the Dom itself. He explained how it took over 600 years for the cathedral to be completed—with a three hundred year gap when nothing was done. It was started in the 13th century and not completed until the 19th. I’ve already mentioned how awesome the Dom is from the outside—the interior is equally breathtaking. The height of the vaults, the almost delicate feel of the structure, and the stained glass windows are magnificent.

After the tour we had a beer along the Rhine with a few people from the tour and then returned to our hotel before dinner in the Belgian Quarter where we once again had Italian food. That made it our third night in a row eating pasta plus the lunch in Gau-Algesheim—and it wouldn’t stop there. German food just didn’t work for us—too much meat, too little fish. It’s a real challenge for someone who is kosher and lactose intolerant. So we ate mostly Italian food throughout the trip. And it was very good. On the other hand, we also ate a lot of delicious German bread, pastries, and pretzels and drank wonderful German beer. My favorite lunch was a fresh German roll with either a hard-boiled egg or smoked salmon. I learned that salmon in German in Lachs—hence, the Yiddish term “lox.” Believe me, we ate quite well—too well!

Our second day in Cologne focused on its Jewish past and present.