Map of Pennsylvania highlighting Allegheny County (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Or how my great-grandfather met my great-grandmother. I love finding stories about how couples met each other. From a little tiny news item in a small local paper in 1887, I may have found a clue as to how my Schoenthal/Katzenstein grandparents met each other.

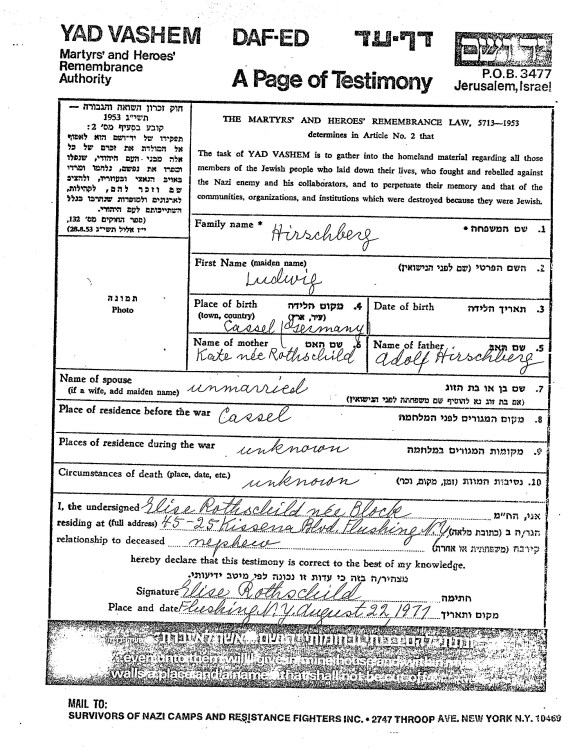

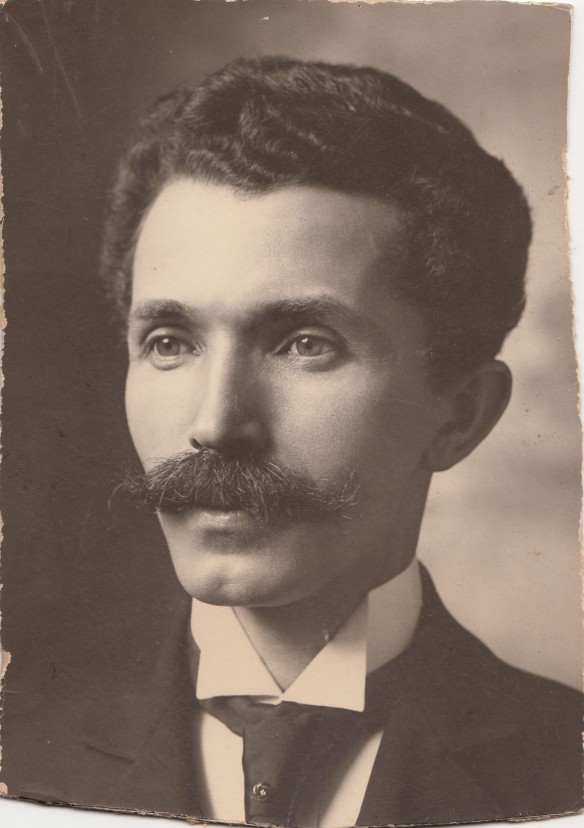

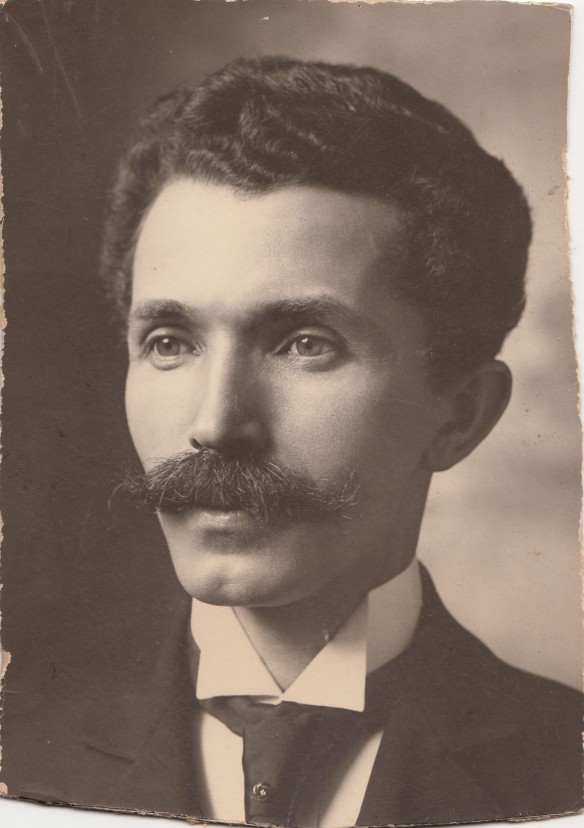

Isidore Schoenthal

By 1880, many of the members of the family of Heinemann Schoenthal and Hendel Beerenstein had moved from Sielen, Germany, to the United States. Their two daughters had arrived first: Fanny and her husband Simon Goldsmith and Mina and her husband Marcus Rosenberg. They were followed by six of the children of Levi Schoenthal (Fanny and Mina’s brother) and Henrietta Hamberg: Henry, Julius, Amalie, Simon, Nathan, and Felix.

Their father Levi died in 1874; their mother Henrietta was still living in Germany in 1880. Four of the children of Levi and Henrietta were also still in Germany in 1880: Hannah, Jacob, Rosalie, and my great-grandfather Isidore. All but Jacob would soon be in the United States.

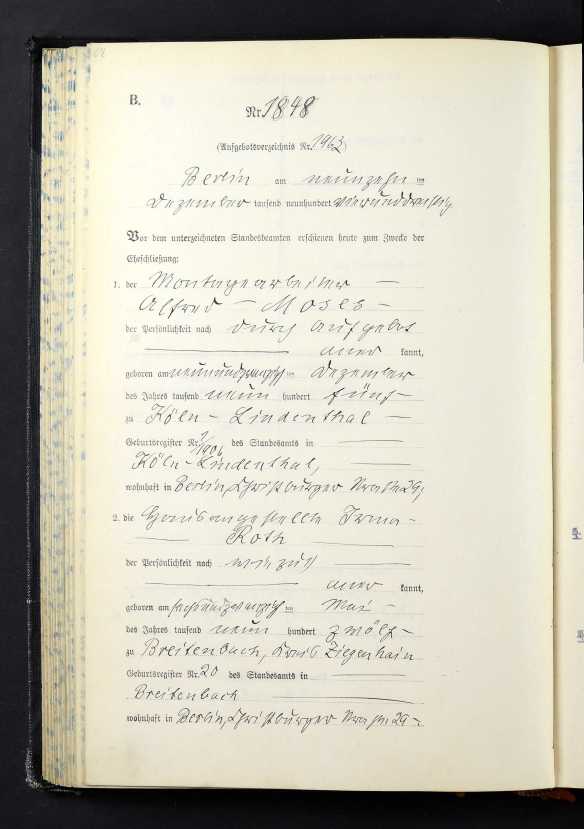

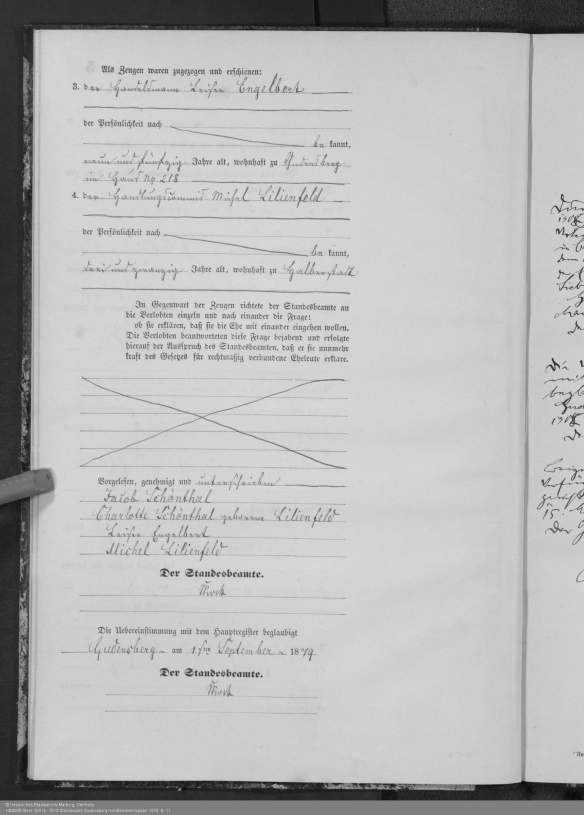

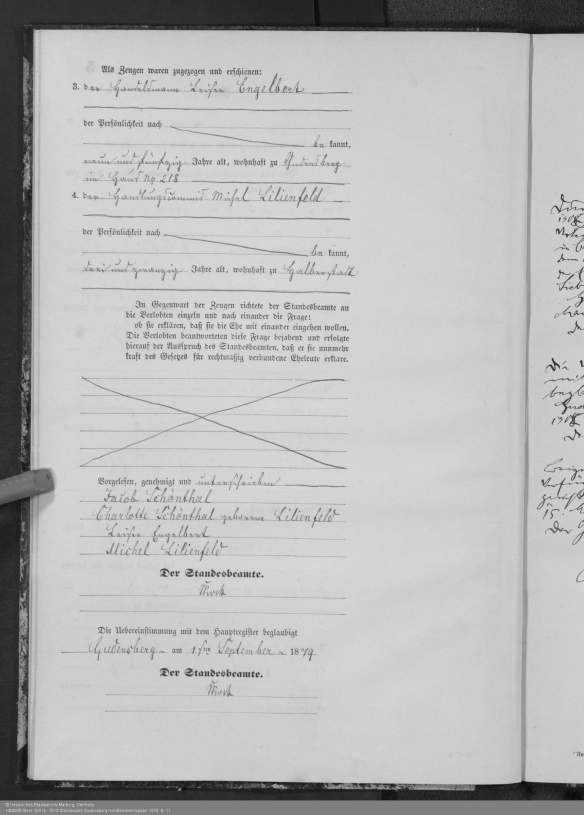

Jacob had married Charlotte Lilienfeld in 1879 and was a merchant living in Cologne (or Koln), Germany. Charlotte was the daughter of Meyer Lilienfeld and Hannchen Meiberg of Gudensberg, another small town in the Kassel district of Hessen, not far from Sielen. Charlotte was the half-sister of Helen Lilienfeld, who had married Jacob’s brother Henry in 1872. Although Jacob and Charlotte never emigrated from Germany, they had two sons who did: Lee, born in 1881, and Meyer, born in 1883. More on them in a later post.

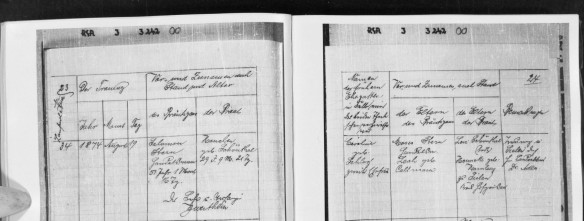

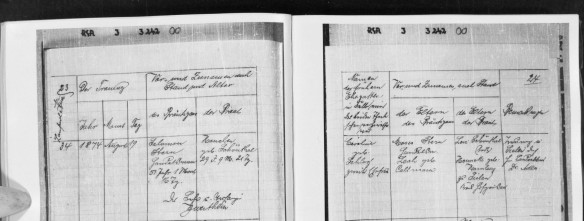

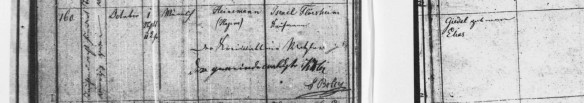

HStAMR Best. 920 Nr. 2610 Standesamt Gudensberg Heiratsnebenregister 1879, S. 10

HStAMR Best. 920 Nr. 2610 Standesamt Gudensberg Heiratsnebenregister 1879, S. 10

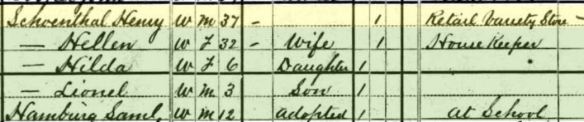

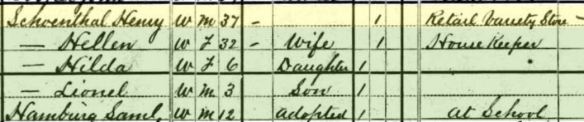

As for the many Schoenthal family members already in the United States, as of 1880 only Henry and his wife Helen (Lilienfeld) and their two young children, Hilda (six) and Lionel (three), were still living in Washington, Pennsylvania, where Henry owned a retail variety store. Living with them and described as their adopted son was a twelve year old boy named Samuel Hamberg, who was born in South Carolina. I have to believe that Samuel Hamberg was somehow related to Henry’s mother’s family, the Hambergs of Breuna, but I cannot find the connection.[1] Henry and Helen would have one more child in the 1880s, a son born in 1883 named Meyer Lilienfeld Schoenthal, named for Helen’s father.

Henry Schoenthal and family 1880 census

Year: 1880; Census Place: Washington, Washington, Pennsylvania; Roll: 1202; Family History Film: 1255202; Page: 596A; Enumeration District: 271

Although Henry was the only Schoenthal sibling still in Washington, Pennsylvania in 1880, others were not too far away. Amalie and her husband Elias Wolfe were now living in Allegheny (today part of Pittsburgh so from hereon I will refer to both Allegheny and Pittsburgh as Pittsburgh), Pennsylvania. According to the entry in the census record, Elias was a “drover.” I’d never heard this term before, but according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary online, a drover is “a person who moves groups of animals (such as cattle or sheep) from one place to another.” Amalie and Elias had three children at the time of the census: Morris was 7, Florence was 5, and Lionel was 2. A fourth child was born in June, 1880, shortly after the census, a son named Ira. Two more were born in the 1880s: Henrietta (1883) and Herbert (1885).

Amalie Schoenthal Wolfe and family 1880 census

Year: 1880; Census Place: Allegheny, Allegheny, Pennsylvania; Roll: 1086; Family History Film: 1255086; Page: 153C; Enumeration District: 006; Image: 0310

As noted in my earlier post, Felix Schoenthal was also still relatively close to Washington, Pennsylvania, living with his wife Maggie in West Newton, about 25 miles away, where Felix was working as a clerk at the paper mill. Felix and Maggie also had two children during the 1880s: Rachel (1881) and Yetta (1884).

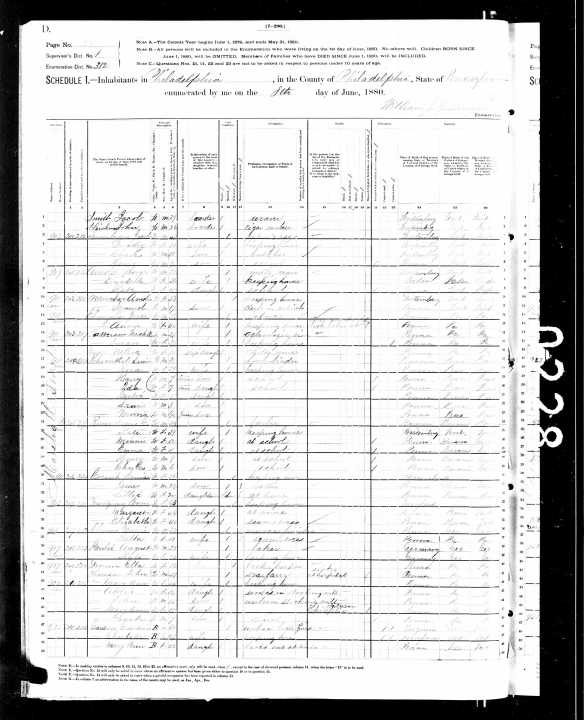

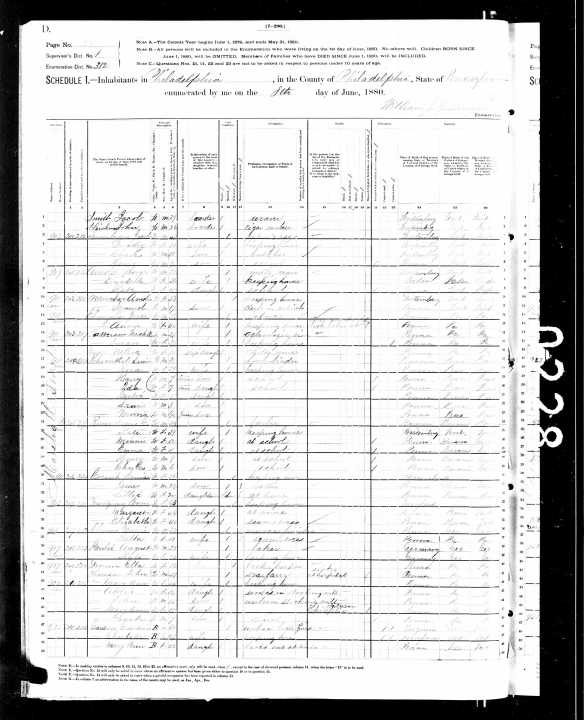

The other siblings had moved further east. Julius was in Washington, DC, working as a shoemaker, as described in my last post. His brother Nathan was also now in DC, working as a clerk in a “fancy store.” Simon Schoenthal had also moved further east by 1880. Although he and his family were living in Pittsburgh in 1879, by 1880 he and Rose and their five children had moved to Philadelphia. Simon was still working as a bookbinder. In the 1880s they would have four more children: Martin (1881), Jacob (1883), Hettie (1886), and Estelle (1889). In 1891, one more child was added to the family, Sidney.

Simon Schoenthal and family 1880 census

Year: 1880; Census Place: Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Roll: 1179; Family History Film: 1255179; Page: 12D; Enumeration District: 382; Image: 0218

But other members of the extended Schoenthal clan still lived in western Pennsylvania. Fanny Schoenthal Goldsmith’s widower Simon Goldsmith was living in Pittsburgh with their daughter Hannah and her family. Hannah’s husband Joseph Benedict was a rag dealer, and in 1880 they had three sons: Jacob (10), Hershel (9), and Harry (3).[2]

Simon Goldsmith and Joseph Benedict families on 1880 census

Year: 1880; Census Place: Pittsburgh, Allegheny, Pennsylvania; Roll: 1092; Family History Film: 1255092; Page: 508D; Enumeration District: 122; Image: 0683

As described in an earlier post, Mina Schoenthal Rosenberg and her husband Marcus Rosenberg and their daughter Julia were living in Elk City, Pennsylvania, in 1880. Their daughter Hannah and her husband Herman Hirsh were living in Pittsburgh with their five children in 1880. Their daughter Mary and her husband Joseph Podolsky and children were living in Ohio. Mina’s other two children, Rachel and Harry, are missing from the 1880 census.

Thus, by 1880, there were still a large number of family members in western Pennsylvania; it was still home to most of the extended Schoenthal clan. It is not surprising that when my great-grandfather Isidore arrived with his mother and sister Rosalie, they ended up in western Pennsylvania as well.

My great-grandfather Isidore, his mother Henrietta Hamberg Schoenthal, and his younger sister Rosalie arrived in New York on September 3, 1881, upon the ship Rhein, which had sailed from Bremen. Isidore was 22, Rosalie was seventeen, and Henrietta was 64 years old. They settled in Washington, Pennsylvania, where Henry was living. Isidore worked as a clerk in Henry’s variety store.

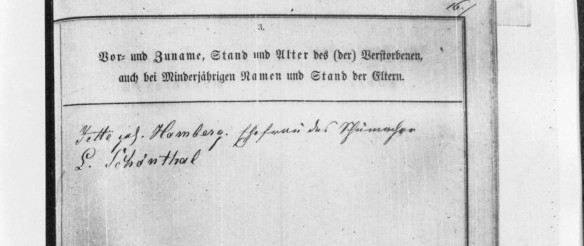

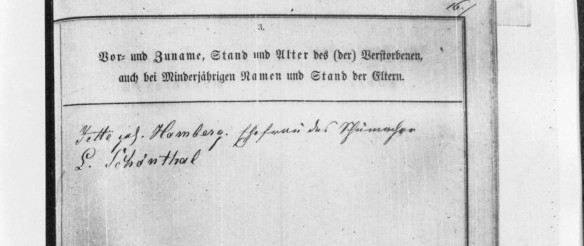

Henrietta died just a year later in December, 1882; she was buried at Troy Hill cemetery in Pittsburgh. Washington did not yet have a Jewish cemetery. Although I could not find an American death certificate, Henrietta’s death was recorded back in Sielen even though she had died in the US.

Henrietta Hamberg Schoenthal death record from Sielen

HHStAW Abt. 365 Nr. 773, S. 10

Henrietta’s brother-in-law Simon Goldsmith died a few months later on March 17, 1883. He also was buried at Troy Hill.

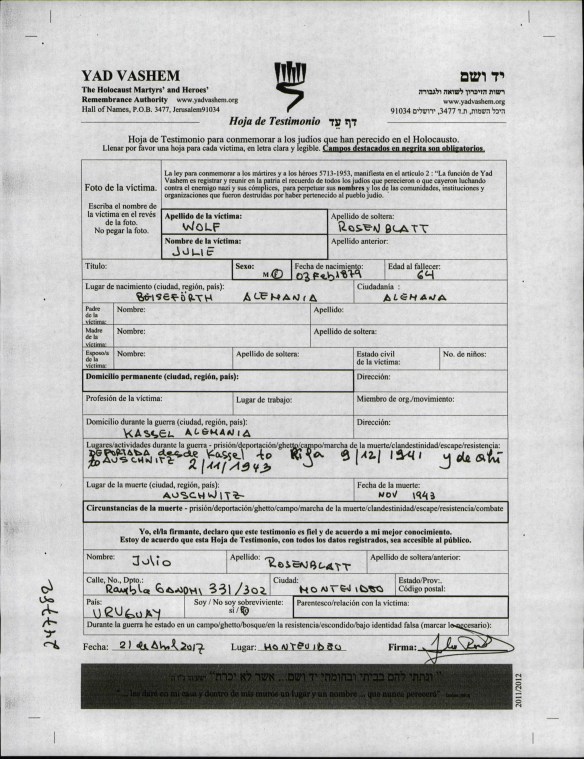

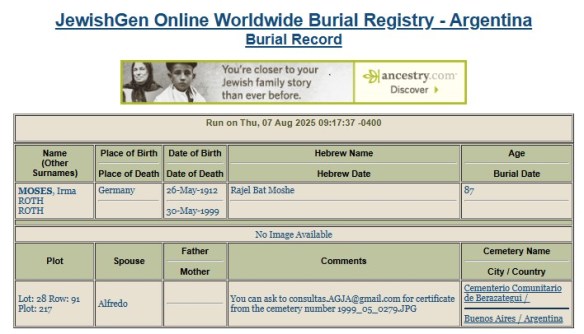

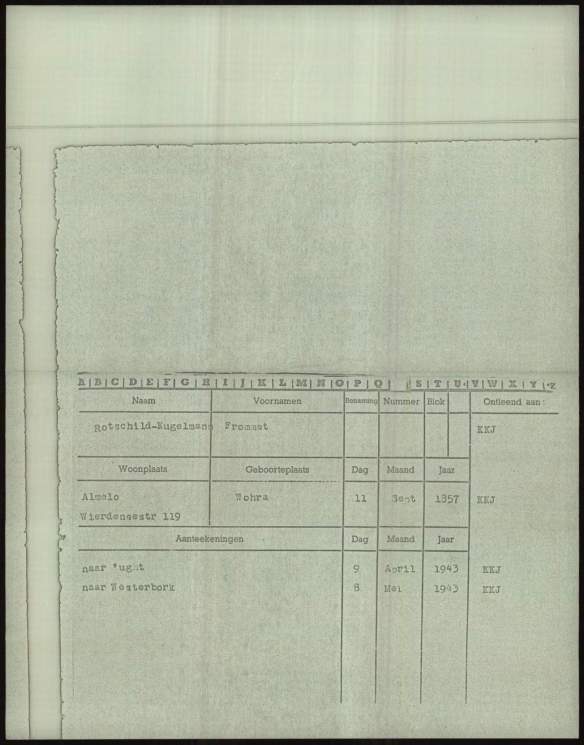

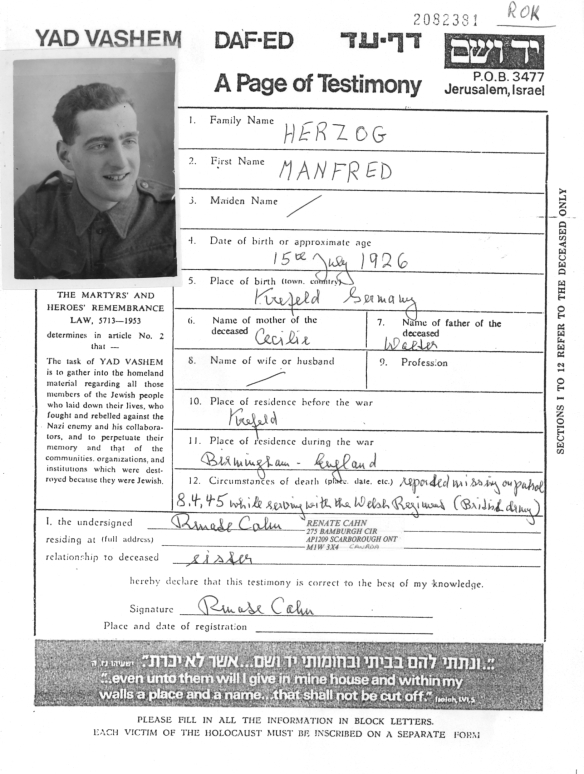

Rosalie Schoenthal, the youngest child of Levi and Henrietta, returned to Germany where she married William or Willie Heymann in Geldern, Germany, on December 8, 1884. She and Willie would have four children born in Geldern: Lionel (1887, for Rosalie’s father Levi, presumably), Helen (1890), Max (1893), and Hilda (1898). I assume that either Helen or Hilda was named for Rosalie’s mother Henrietta. The two sons ended up immigrating to the United States; the two daughters and their families perished in the Holocaust. But more on that in a later post.

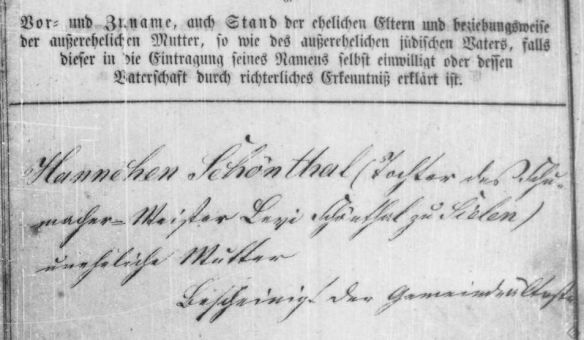

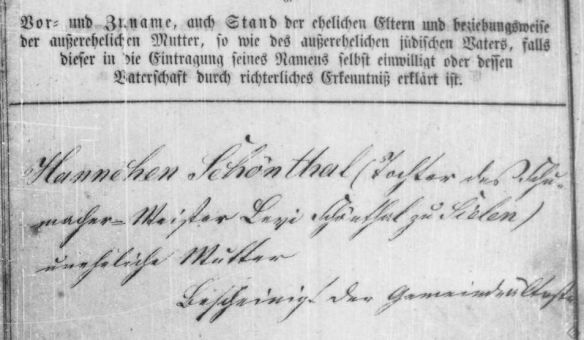

There would be one more Schoenthal sibling who would immigrate to the US: the oldest child, Hannah. Hannah had had a child out of wedlock in 1865, a daughter named Sarah whose father is unknown.

birth of Sarah Schoenthal, daughter of Hannah Schoenthal, in Sielen, 1865

HHStAW fonds 365 No 772 p12

[Translation: “Hannchen Schönthal (Tochter des Schuhmacher=Meister Levi Schönthal zu Sielen) uneheliche Mutter.”…..Hannchen Schönthal (daughter of the master shoemaker (cobbler) Levi Schönthal of Sielen) unmarried mother.]

Hannah later married Solomon Simon Stern in Sielen, Germany, on August 19, 1874, five months after her father Levi died. She was 29 years old at that time. Solomon was 57.

Marriage of Solomon Stern to Hannah Schoenthal in Sielen

HHStAW Abt. 365 Nr. 839, S. 22

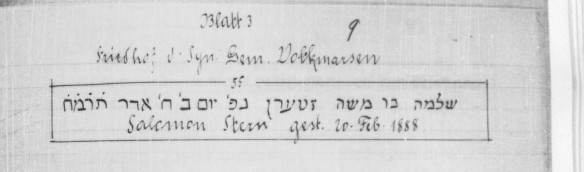

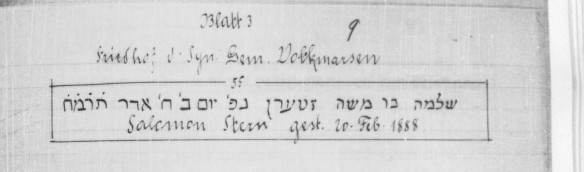

Together they would have three children: Jennie, born June 20, 1875; Edith, born September 7, 1877; and Louis, born May 17, 1879. Solomon Stern died February 20, 1888, and Hannah and their three children emigrated from Germany shortly thereafter. According to later census records, Hannah and the three children all emigrated in 1888.

Solomon Stern gravestone inscription

HHStAW Abt. 365 Nr. 842, S. 11

Hannah and her children settled in Pittsburgh, where her sister Amalie and her husband Elias Wolfe and their six children, named above, were still living. Elias continued to work as a drover. Hannah and Amalie’s brother Felix also was in Pittsburgh by that time, having relocated there from West Newton by 1882. He was working as a bookkeeper. In 1889 he opened his own store:

Pittsburgh Daily Post, 9 Apr 1889, Tue, Page 3

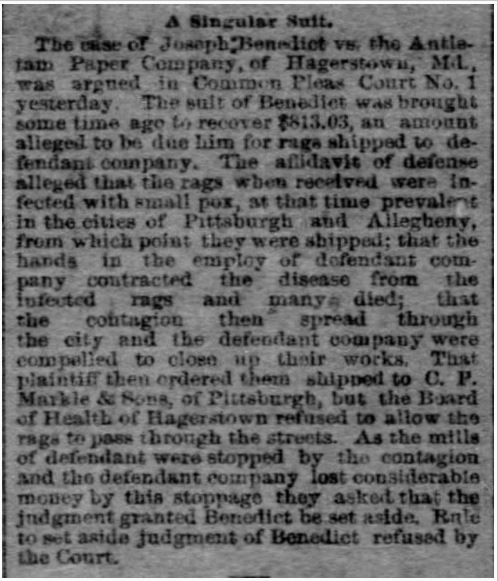

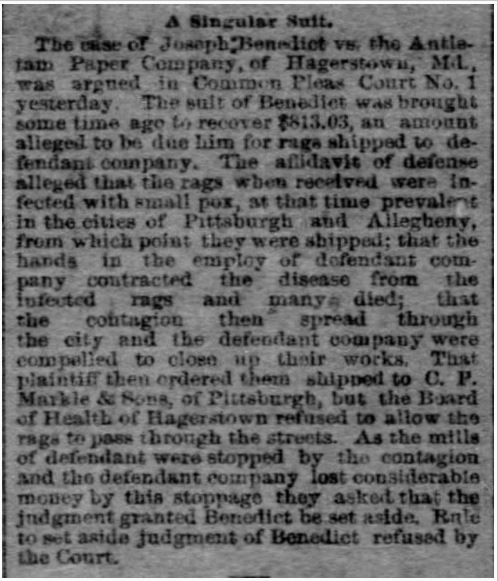

Also living in Pittsburgh in the 1880s was their Schoenthal cousin, Hannah Goldsmith Benedict, and her husband Joseph and three children, Jacob, Herschel, and Harry; Joseph was selling rags and paper stock. Joseph became entangled in a rather gruesome lawsuit involving the sale of rags to a paper mill. The purchaser had failed to pay the purchase price, and Joseph had sued for payment. The purchaser alleged that they were not liable for the purchase price because the rags had been infected with the smallpox virus, and several of the purchaser’s employees had taken ill, causing the shutdown of the purchaser’s mills. Thus, the purchaser claimed it had been damaged by loss of business in an amount exceeding what it allegedly owed Joseph Benedict.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 5 Sep 1882, Tue, Page 1

This would have been a fun case for me to teach in my days as a law professor teaching Contracts. It is similar to a famous case taught in most Contracts courses called Hadley v. Baxendale. Was the shutdown of the paper mill a foreseeable consequence of the seller’s defective product? Here there are also issues of negligence, breach of warranty, damages, and so on. It would have been a great exam question. Fortunately for Joseph Benedict, the court refused to set aside the judgment in his favor, and the paper mill was held liable for the purchase price of the rags.

Another Schoenthal cousin, Hannah Rosenberg Hirsh, and her husband Herman and their five children, Morris, Nathan, Carrie, Harry, and Sidney, were also living in Pittsburgh; Herman was in the varnish business, at first for the Michigan Furniture Company and then in his own business manufacturing varnish.

Hannah thus had many family members close by in Pittsburgh to provide support as she raised her three children alone in the new country.

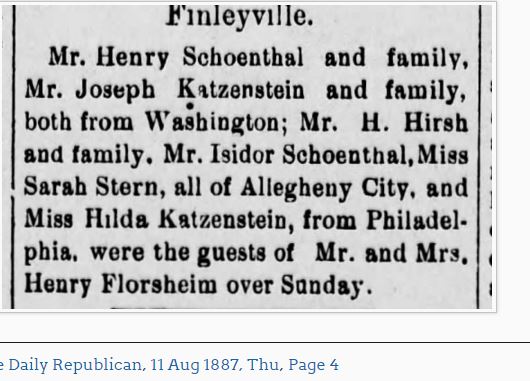

My great-grandfather Isidore lived in Pittsburgh for some time also around 1887 through 1889, working as a floor walker in a retail store, at least according to the listings in the Pittsburgh city directories for those years. But sometime in early 1888 he married my great-grandmother Hilda Katzenstein in Philadelphia. Hilda was the daughter of Eva Goldschmidt and granddaughter of Seligmann Goldschmidt. As discussed in an earlier post, Seligmann Goldschmidt was the brother of Simon Goldschmidt, who became Simon Goldsmith and who had married Isidore’s aunt, Fanny Schoenthal. Thus, Hilda and Isidore were already related to each by marriage. In addition, Hilda’s brother S.J. Katzenstein was a merchant, living in Washington, Pennsylvania. I don’t know whether my great-grandparents met through S.J. in Washington, Pennsylvania, or through their mutual cousins, the Goldsmiths, or perhaps even through Isidore’s brother Simon, who lived in Philadelphia, where Hilda had been born and raised.

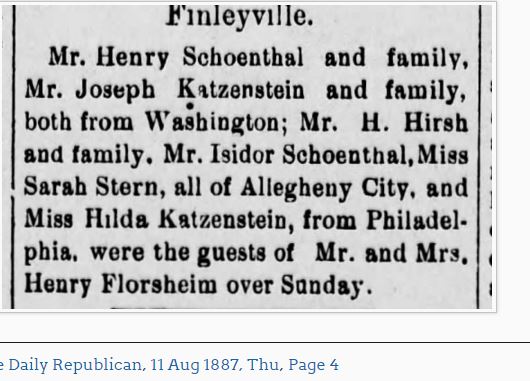

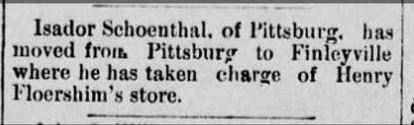

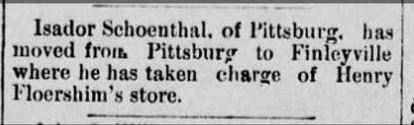

But I did find this important clue:

The Daily Republican

(Monongahela, Pennsylvania)

11 Aug 1887, Thu • Page 4

Was this when Isidore and Hilda met—at a gathering at the house of a man named Henry Florsheim who lived in Finleyville? And who was he? A little research revealed that Henry Florsheim was born in 1842 in Gudensberg, Germany, the same town where Helen and Charlotte Lilienfeld were born, the wives of Henry Schoenthal and Jacob Schoenthal, respectively.

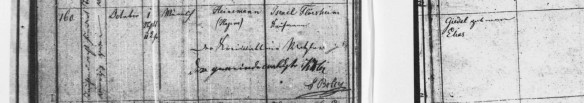

Henry (Heinemann) Florsheim birth record from Gudensberg

HHStAW Abt. 365 Nr. 384, S. 35

In fact, according to research done by Hans-Peter Klein as reflected on his incredibly helpful website found here, Henry Florsheim’s sister married Helen Lilienfeld’s brother in Gudensberg in 1872, the same year that Helen Lilienfeld married Henry Schoenthal. According to the 1910 census, Henry Florsheim came to the US in 1876, so the two families were already related by marriage when he arrived. In 1880 Henry Florsheim was a merchant, living in Union Township in Washington County, Pennsylvania, about 20 miles from the city of Washington, PA. An article in the January 31, 1887, Pittsburgh Daily Post (p.4) , reported that he was the proprietor of the Union Valley coal mines and had been presented with a gold watch by the citizens of Finleyville, a town about 16 miles from Washington and two miles from Union Township. Thus, in just a decade, Henry Florsheim had made quite a mark on his community. Was this successful businessman the one who was responsible for bringing my great-grandparents together? If so, thank you, Mr. Florsheim![3]

Hilda Katzenstein Schoenthal

That was not the end of Henry Florsheim’s role in my great-grandparents’ lives. In 1889, he hired my great-grandfather to work in his store in Finleyville; this news article suggests that they were still living in Pittsburgh before that opportunity arose.

The Daily Republican

(Monongahela, Pennsylvania)

8 Nov 1889, Fri • Page 1

Isidore and Hilda’s first child, my great-uncle Lester Henry Schoenthal, was born on December 3, 1888. I assume that, like all the Lionels and Leo and Lee, he was named for Isidore’s father Levi. About three years later on January 20, 1892, Isidore and Hilda had a second son, Gerson Katzenstein Schoenthal, named for Hilda’s father. Their third child, Harold, and their fourth and youngest child, my grandmother Eva, would not arrive until after the 20th century had begun.

Thus, by 1890, the Schoenthal family had deep and wide connections to western Pennsylvania. My next post will catch up with those family members who were living elsewhere in the 1880s: Washington DC, Ohio, and Philadelphia.

[1] All I can find about Samuel’s background is that he appears to have been the son of Charles Hamberg, who was born in Germany and emigrated before 1850; in 1853, Charles married Mary E. Hanchey in New Hanover, North Carolina. She, however, was not Samuel’s mother because she was murdered on November 18, 1866. On the 1870 census, Charles was living with a 21 year old woman named Tenah Hamberg and two year old Samuel. Since the 1870 census did not report information about the relationships among those in a household, I don’t know for sure whether Tenah was Charles’ wife or Samuel’s mother. Charles died in 1879, and the administrix of his intestate estate was a woman named Amalia Hamberg. I don’t know who Amalia was or how she was related to Charles. But by 1880, twelve year old Samuel had moved to Washington, Pennsylvania, to live with Henry.

[2] There were also two young boys, Jacob and Benjamin Goldsmith, living with them and a 21 years old named Jacob Basch. They were labeled “grandsons,” but they had to be Simon’s grandsons, not Joseph and Hannah’s grandsons. Jacob Basch was the son of Simon’s daughter Lena from his first marriage, who had married Gustav Basch. I don’t know who the parents of Jacob and Benjamin Goldsmith were.

[3] That little article about Henry Florsheim’s party also led me to another question: who was the woman named Sarah Stern who also attended this gathering? I assumed she must have been a relative since everyone else at the Floersheim event was part of the Schoenthal or Katzenstein families, and I only knew of one Stern in the family—Solomon Stern who had married Hannah Schoenthal, the older sister of Henry, Isidore, and the other children of Levi Schoenthal. Hannah’s first child, born before she married Solomon Stern, was named Sarah. Was this Sarah Stern the same person, taking on her stepfather’s surname? Further investigation would support that conclusion, as I will describe in a later post.