After lunch in Mainz on May 3, Wolfgang drove us to Bingen, where we were scheduled to meet Beate Goetz. Beate, who volunteers at the Arbeitskreis Judische in Bingen, is one of the many German researchers who have helped me with my research. Over the last two years she has sent many records of our Seligmann relatives from the Bingen region, and she has been extremely helpful so I was looking forward to meeting her. She had volunteered to show us around Bingen. It was wonderful to meet her and spend time with her; she is one of the many dedicated people working to preserve the Jewish history of Germany.

In researching my Seligmann family, I had learned that my 4x-great-grandfather Jacob Seligmann and my three-times great-grandfather Moritz Seligmann were both born in Gaulsheim, a village that is now a part of Bingen. I had wanted to see Gaulsheim, but Beate assured me that there was really nothing to see as all the old houses were gone. Now it is just a residential area outside the main center of Bingen. So we focused instead on the center of the city itself.

Bingen is located at the junction of two rivers—the Rhine and the Nahe. It is a small city; today its population is about 25,000 people. Our hotel, the Roemerhof, overlooked the Nahe river (which we could see if we peered between two buildings outside our window). While walking along the river, we saw ducks swimming along. The region is known for wine-making, and we could see vineyards in the hills surrounding the city.

There is evidence that Bingen was settled as early as Roman times, and its location gave it strategic importance as a gateway to the Rhine Valley region. There was a Jewish community in Bingen at least as early as the 12th century. Although the Jews were expelled from Bingen in both the late 12th century and the 16th century, they returned and resettled. Jews worked as money lenders in the earliest times, but in later times, Jews like my own relatives were merchants and wine traders. In 1933 there were 465 Jews living in Bingen. Half left by 1939, and those who remained were deported. Only four returned. Today there is a small number of Jews from Russia living in Bingen, but no real synagogue or formal Jewish community.

Bingen suffered extensive damage by Allied bombing during the war, and parts of the the city today are not particularly pretty, although there are still lovely winding streets and open squares throughout the city, some lined with older buildings and homes. Many of the buildings, however, are post-war concrete construction that do not have much aesthetic appeal.

Beate took us to see two former synagogue buildings. The first had been closed by the Jewish community itself in 1905 because the community, numbering at that time about 700 people, needed a larger space. Today it is used as a youth center.

The second synagogue, which opened in 1905, was once quite a grand building. Here are some photographs from the Arbeitskreis Judsiche Bingen of what it looked like before 1938 as well as a model showing what the exterior looked like:

Like so many synagogues across Germany, it was partially destroyed by fire in November, 1938, on Kristallnacht. After the war the building was sold, as there was no longer a Jewish community that needed it. Most of the building was taken down, but part remains. Today part of it houses the Arbeitskreis Judische and provides a meeting space for the Russian Jews who live in Bingen.

Beate also took us to several homes where some of our Seligmann cousins had once lived. We saw the house that had belonged to Bernhard Gross and his wife, Bertha Seligmann. Bertha was my first cousin, four times removed. Her grandparents were Jacob Seligmann and Martha Mayer, my 4x-great-grandparents; her mother, Martha Seligmann, was the sister of Moritz Seligmann, my three-times great-grandfather. Bertha and Bernard died from carbon monoxide poisoning in their own home in 1901, as I wrote about here.

We also saw the former home of Bertha and Bernard’s daughter Mathilde Gross and her husband Marx Mayer. Mathilde is the cousin whose memoir inspired me to start learning German. (I still am not fluent enough to read it with much ease, however.) Her husband Marx died in 1934, but Mathilde and all their children emigrated from Germany in the 1930s and were able to survive the war.

As you might imagine, seeing these two stately and large homes made me realize how successful the family had been and thus how much they had lost when they left Germany.

We also saw a number of stolpersteine, including these three for the family of Karl Gross, who was Mathilde Gross Mayer’s brother. Karl Gross, his wife Agnes Neuberger, and their daughter Bertha Gross were all killed in the Holocaust. Karl was was my second cousin, three times removed. His grandparents, Jacob Seligmann and Martha Mayer, were my 4x great-grandparents. I wrote about the Gross family here.

Stolpersteins for Karl Gross and his family

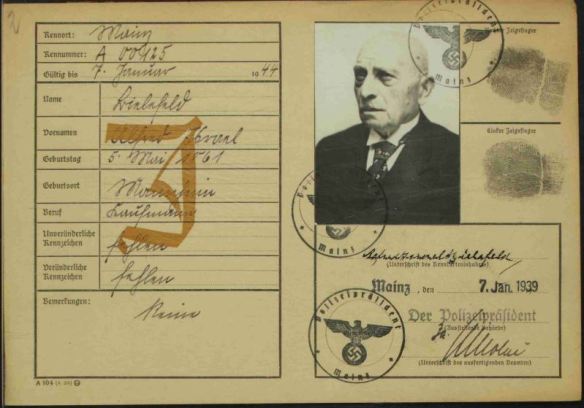

Finally, Beate pointed out to us the location of the former shoe store owned by the family of Joseph Wiener. Joseph Wiener married my cousin Anna Winter, daughter of Samuel Oskar Wiener and Rosina Laura Seligmann. Rosina was the daughter of Hyronimus Seligmann, brother of my great-great-grandfather Bernard Seligman. Rosina was thus also the sister of Johanna Seligmann Bielefeld, whose house in Mainz I’d seen the day before. Rosina and her husband were both murdered in the Holocaust; their only son had been killed serving Germany in World War I. Anna and Joseph survived and immigrated to the US in 1938. Their daughters, Doris and Lotte, wrote the moving memoirs I was honored to excerpt on my blog here, here, here, and here.

Thus, as we left the downtown area of Bingen to drive to the Jewish cemetery up the steep hill from the town, I had the thoughts of all these cousins in my head. The people behind the names and stories I’d researched and studied suddenly felt very close and very real. Seeing some of the additional names in the cemetery made me appreciate how deeply connected my Seligmann relatives had been to the Bingen community.

The cemetery is a large and peaceful place. There are about a thousand headstones there in a beautiful wooded area overlooking the valley below. It was overwhelming. I took many photographs, and I hope to be able to get some of them translated. Here are just a few of the stones we saw for my Seligmann relatives.

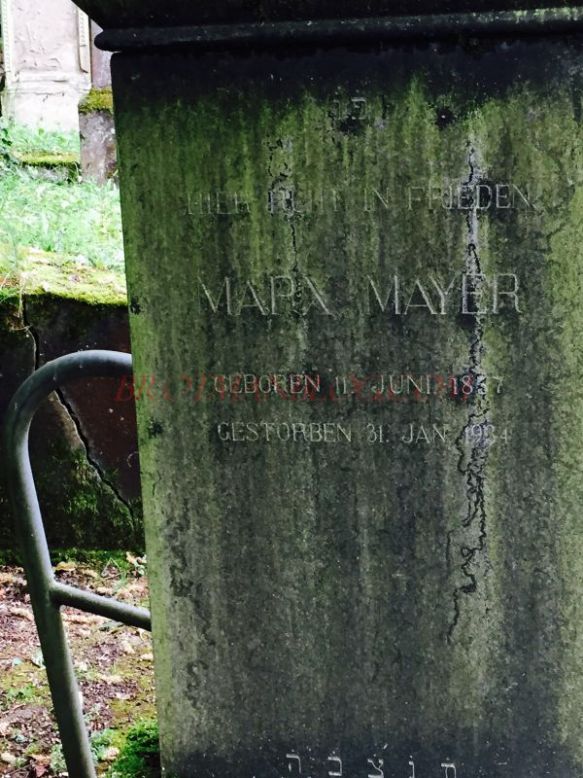

Marx Mayer, husband of Mathilde Gross, granddaughter of Jacob Seligmann and Martha Mayer, my 4x-great-grandparents:

Ferdinand Seligmann and Lambert Seligmann: brothers of Bertha Seligmann. My first cousins, four times removed.

Hermann Seligmann, brother of Ferdinand, Lambert, and Bertha.

Ludwig or Louis Seligmann, son of Isaak Seligmann and another grandson of Jacob Seligmann and Martha Mayer. Another first cousin, four times removed.

Wife of Louis Seligmann, Auguste Gumbel

Emilie Seligmann Lorch. daughter of Benjamin Seligmann and Martha Seligmann (who were first cousins). Martha Seligmann was the sister of Moritz Seligmann, my 3x-great-grandfather. She was my 4x great-aunt.

There were probably many, many more of my Seligmann cousins buried in Bingen’s Jewish cemetery, but many stones were impossible to read, and the sheer volume of stones made it overwhelming to think about searching for more. I took some additional photographs of stones that would need translating from Hebrew, but I had to accept that there was no way to find and photograph every headstone in the cemetery in the limited time we had.

By the end of our afternoon in Bingen, it was clear to me that this city had been at one time the place where most of my Seligmann relatives and ancestors had lived. Although I had not found the gravesites or homes of any of my direct ancestors, I knew that many of my cousins had lived and died in Bingen, sadly some at the hands of the Nazis. Bingen was the home of the earliest Seligmann ancestors I’ve found, Jacob and Martha (Mayer) Seligmann back in late 18th century, and there were Seligmann descendants still living there in the 20th century.

We would return to Bingen the following evening for dinner, but first on the following day we were to visit Gau-Algesheim, where my great-great-grandfather Bernard was born and lived until he came to America in the1840s.