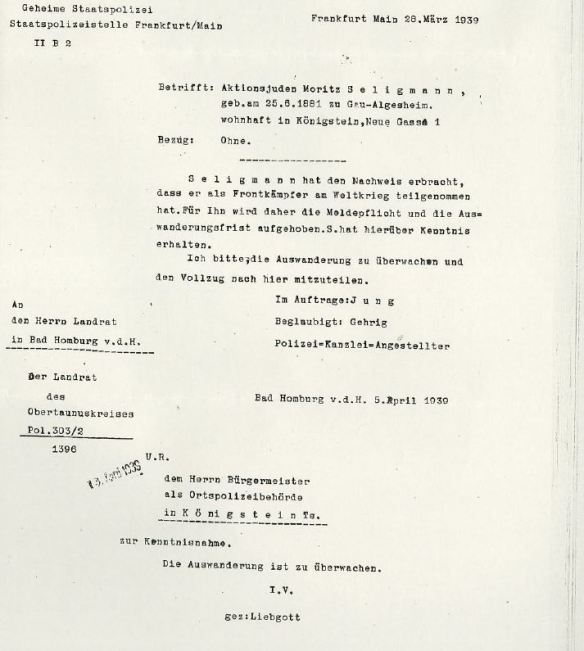

Way back on November 22, 2014, I wrote very briefly about a cousin named Fred Michel. He was mentioned in Ludwig Hellriegel’s book about the Jews of Gau-Algesheim as the son of Frances (Franziska) Seligmann and Max (Adolf?) Michel. Frances was the daughter of August Seligmann. Since August Seligmann was my great-great-grandfather Bernard Seligman’s brother, his grandson Fred Michel would be my second cousin, twice removed. According to Hellriegel’s book, Fred had escaped to the United States in 1937 after his mother died in 1933. That was all I knew, and the name Fred Michel was common enough in the US that I had no way of narrowing it down to the right person based on the name alone.

Well, one email from my cousin Wolfgang opened up an entirely new door of research for me. In his email, Wolfgang mentioned Fred Michel, the nephew of his grandfather Julius. In that email, Wolfgang said that Fred had settled in Scranton, Pennsylvania. From that one additional bit of information, I was able to find Fred and his wife Ilse on the 1940 census in Scranton living as boarders in the household of other German immigrants. I also found them in several Scranton directories.

Year: 1940; Census Place: Scranton, Lackawanna, Pennsylvania; Roll: T627_3685; Page: 7A; Enumeration District: 71-106

I also found Fred’s enlistment record in the US army in July 1943 on the Ancestry index. That led me to his Veteran’s Burial Card, showing that he had served from July 1943 until September 1945 and that he had died on August 5, 1992, and was buried at Temple Hesed cemetery in Scranton.

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission; Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; Pennsylvania Veterans Burial Cards, 1929-1990; Archive Collection Number: Series 2-4; Folder Number: 655

Since I also had learned that his wife’s name was Ilse, I researched what I could about Ilse. She was also born in Germany, and at least according to the 1940 census, she’d been living in Frankfort, Germany in 1935. I found various public records indicating that Ilse and Fred were still living in Scranton as of 1989, and I also found Ilse on the Social Security Death Index, indicating that she had died on July 22, 2002.

But I wanted to know more, and so I googled their names, Fred and Ilse Michel, with Scranton, and I found a gold mine. Fred and Ilse donated their papers to the Leo Baeck Institute, and the papers have been digitized and are available online. This is the description provided for the Michel papers, known as the Ilse and Fritz Michel Family Collection, AR 25502, at the Leo Baeck Institute:

“This collection contains personal and official documents pertaining to the family’s immigration to the United States and their situation in Germany as the political climate deteriorated. Included are a large amount of personal letters, supplemented by various other documents from government and military offices, some genealogical and tracing certificates, as well as other various material.”

In addition, the Leo Baeck Institute provided this biographical note for Ilse and Fred Michel:

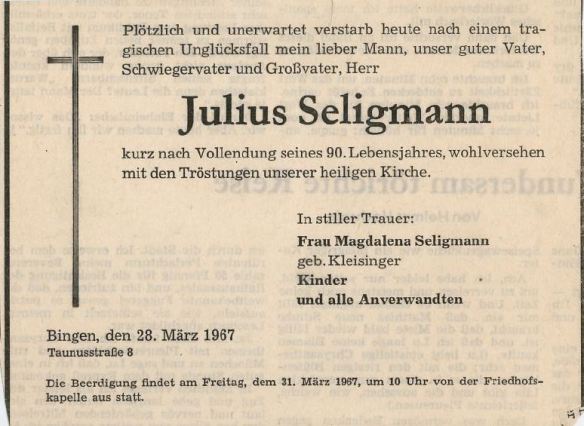

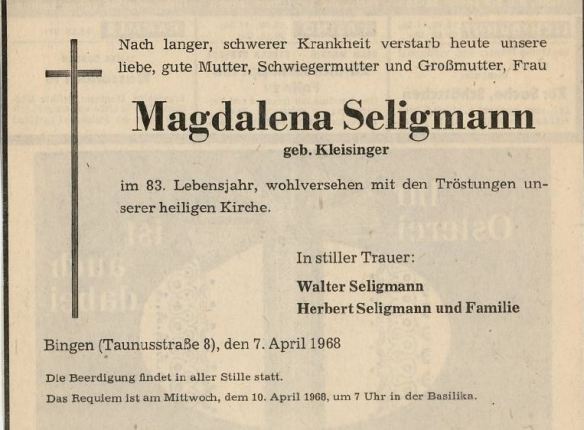

Fritz (Fred) Michel (1902-1992) was born in Bingen am Rhein, Germany, the son of Adolf Michel and Franziska Michel, née Seligmann. Fred Michel’s wife, Ilse Hess (1911-2003), was born in Leipzig, daughter of Hermann Hess and Helene Hess, née Hirschfeld (1866-1943). Hermann Hess died in 1922 in Frankfurt am Main. After having been denied immigration to the U.S., Ilse’s mother Helene was deported to Theresienstadt in 1942, where she died in 1943.

Fritz (Fred) Michel emigrated from Frankfurt am Main to the U.S. via Antwerp, Belgium, in 1937. In the U.S. he changed his name to Fred. Ilse emigrated a year after that, via Hamburg, in 1938. Upon immigration Fred and Ilse remained separated for about two years, working in various areas in the state of New York, before they eventually settled in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1939, where they were married in 1940. There, Ilse started up a millinery business, while Fred maintained a position as bartender. They became naturalized citizens in 1943. The same year Fritz joined the U.S. army and served until 1945. They remained in Scranton for the rest of their lives.

There is truly a treasure trove in the collection—letters, documents, passports, photographs. Many of the letters are in German, and I am hoping to find some way to translate them. I also want to obtain permission to post some of the documents included in the collection if I can.

For now I can highlight some of the facts I was able to learn from the documents that are in English. Before coming to the United States in 1937, Fred had worked for Bamberger and Hertz, a men’s clothing store with several locations in Germany; Fred had worked for them in Cologne, Frankfort, and Munich between 1931 and 1936. On the website for the Jewish Museum in Berlin, I found an article and photograph about Bamberger and Hertz and the effect Nazism had on the business. The photograph depicts Nazi storm troopers posting leaflets on the store windows, warning people not to patronize this Jewish-owned business.

After the April Boycott sales declined at all the stores. The Saarbrücken branch closed in 1934 and a buyer was found for the Frankfurt store in 1935. The branches in Cologne, Stuttgart and Leipzig were forcibly sold or dissolved in 1938. In October of the same year Siegfried Bamberger managed to sell the Munich business to his trusted long-time employee Johann Hirmer. Although the transaction aroused the Nazis’ suspicions, it was carried out within the bounds of the law.

It is thus not surprising that Fred Michel would have left his home and his long-time employer in 1937.

According to Fred’s application for naturalization as a US citizen, he arrived in the United States on September 24, 1937, aboard the SS Koenigstein, departing from Antwerp, Belgium, and traveling tourist class. He had been examined by US immigration officials in Stuttgart before departing.

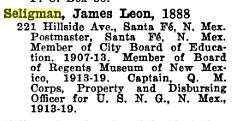

Of great interest to me was that Fred listed his sponsor as James Seligman of 324 Hillside Drive in Santa Fe, New Mexico. James Seligman. This must have been my great-grandmother Eva Seligman’s younger brother James. How did Fred Michel know him? To me, this makes it evident that my great-grandmother’s family was very much in touch with their relatives still in Germany when Hitler came to power. What were they thinking about Hitler and the Nazis? How did James get involved with helping Fred? Perhaps one of those letters in German will reveal more.[1]

After arriving in the United States, Fred first lived in New York City and worked at a business called Burrus and Burrus for a year. He then worked at the Hebrew National Orphan House in Yonkers, New York. After that, he worked for a furniture company in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, for a year, and then finally settled in Scranton in June, 1939. He worked in a couple of dress shops and then as a bartender at various clubs up to the time of his citizenship application in 1942.

Fred and Ilse were married by a rabbi on January 16, 1940, in Scranton. As of September, 1942, when they applied for citizenship, Fred and Ilse did not have any children. After studying at night school, Fred became a naturalized citizen in June, 1943, shortly before he enlisted in the Army, as described above. According to Fred’s honorable discharge papers from the Army in 1945, he served in Panama during World War II and received a Good Conduct medal, an American Theater Medal, and a World War II Victory medal. He was responsible for handling secret documents, correspondence, and publications during the war.

Ilse became a naturalized citizen in December, 1943. She had arrived in New York in April, 1938, after being examined by US immigration in Stuttgart. She had lived in Woodmere, Long Island, New York, and Mt. Vernon, New York, and New York City before settling in Scranton in December, 1939. She had worked as a bank teller and for various millinery houses during that time. Like Fred, she had attended night school to become a US citizen.

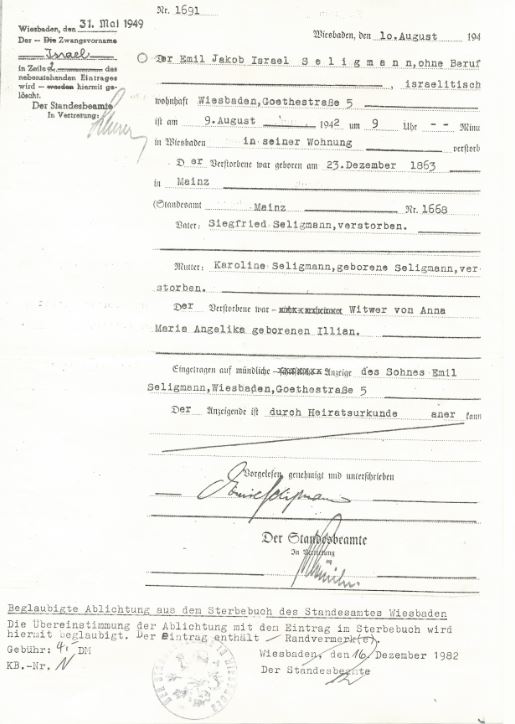

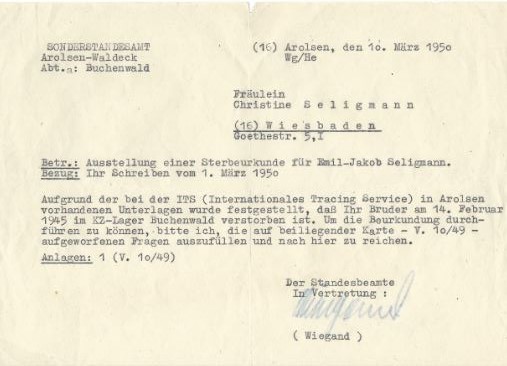

After the war, Fred and Ilse attempted to learn what had happened to their family members back home. Since most of these documents are in German and need to be translated, I will report on their heart-breaking efforts once I can be sure I am reading the documents correctly.

I don’t know from the collection much about Fred and Ilse’s life after the war. I did find a Letter to the Editor of Life Magazine in the July 20, 1962, issue; it reveals some of the obstacles Fred had to overcome as a young boy and also some of his own nostalgia for his native country, even after all the horrors of the Holocaust:

Life Magazine, July 20, 1962, p.21, at https://books.google.com/books?id=KE4EAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA21&lpg=PA21&dq=fred+michel+scranton&source=bl&ots=moOKx_x4yk&sig=BqWqe8Sr7jmbRCraFCf8O29R334&hl=en&sa=X&ei=3uErVbv4IIuiNq75gdAD&ved=0CCAQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=fred%20michel%20scranton&f=false

Wolfgang has a number of letters written by Fred to Walter Seligmann, Wolfgang’s uncle, and he is going to translate those for me. Wolfgang also sent me a copy of a letter that Fred received from the National Westminster Bank in England in December, 1982, regarding the estate of the other James Seligman, brother of Bernard and August and the other children of Moritz Seligmann and Babetta Schoenfeld. Like Pete’s family and Wolfgang’s family, Fred received notification of his rights to inherit some of James estate.

I don’t know whether or not Fred ever obtained his share of the estate. He died ten years after receiving this letter. From Fred’s death certificate, I learned that he had been a quality control officer for a clothing manufacturer. He and Ilse were members of Temple Hesed in Scranton, and both are buried in its cemetery.

I have written to the Leo Baeck Institute and am hoping they can help me as well as give me permission to post some of the documents included in the collection. From what I have read, I only know the surface of what is obviously a much deeper story, a story of two people who escaped and survived, tearing themselves away from their homeland and their family just in time. What was it like for them to leave? What did they know of what was happening in Germany once they left? How did they adjust to living in the United States? How were they received?

There are so many questions, and I am hoping that the materials I cannot yet read in the collection will answer some of them.

[1] This is also the same James Seligman whose son was Morton Tinslar Seligman, the Navy Commander whose career I described extensively here, here, and here.

![By Karsten Ratzke (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/1024px-frankfurt_schumannstrac39fe_15.jpg?w=584&h=388)