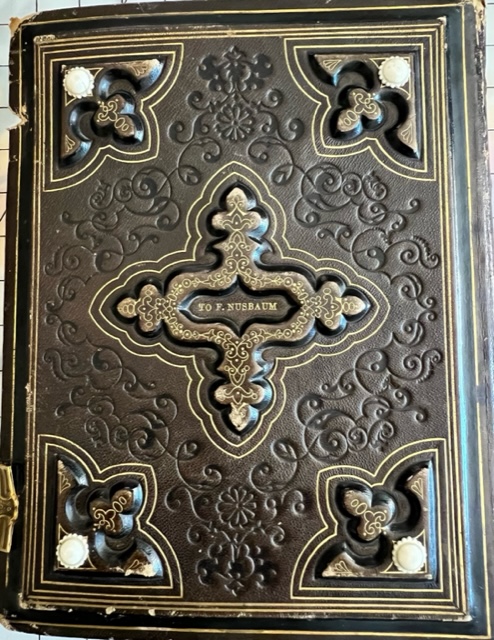

I decided to move on from the Philadelphia photographs in the Nusbaum Album even though there were still many more of them in the album because it seemed to be unlikely that I would ever identify anyone. I asked Ava to focus next on the six photographs taken in Sante Fe, hoping that they would more clearly be of my Santa Fe relatives.

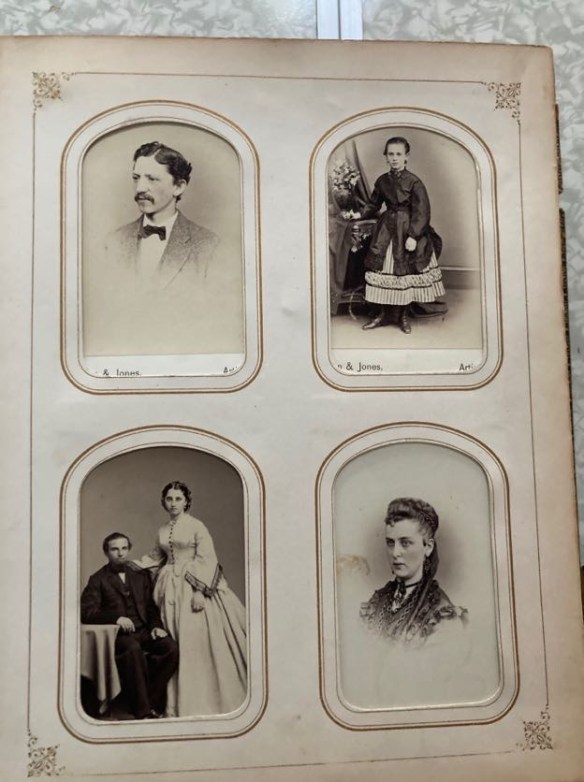

Of those six, three were of young children, two were of adult men, and one was of a couple. My hope was that the couple would be Frances Nusbaum and Bernard Seligman, my great-great-grandparents, the children would be their children, and the two men would be other Seligmans or Nusbaums.

Once again there were no tax stamps on these photographs, so Ava concluded that they were taken either before August, 1864, or after August, 1866. Since Bernard and Frances didn’t move to Santa Fe until after 1868, I was hoping that the photographs fell into that later period. These photos also appear more than halfway into the album so were perhaps later than those 1863 to 1870 Philadelphia photographs Ava had already analyzed.

Once again there were no tax stamps on these photographs, so Ava concluded that they were taken either before August, 1864, or after August, 1866. Since Bernard and Frances didn’t move to Santa Fe until after 1868, I was hoping that the photographs fell into that later period. These photos also appear more than halfway into the album so were perhaps later than those 1863 to 1870 Philadelphia photographs Ava had already analyzed.

The three photographs of children were all taken by the same photographer, H.T. Hiester. Ava’s research of Hiester revealed that “Henry T. Hiester came to Santa Fe from Texas in the summer of 1871 at the request of Dr. Enos Andrews. Hiester was active in Santa Fe from 1871-1878. He had a studio in West Side Plaza from 1871-1874 and one on Main Street from September, 1874 to March, 1875.”1

Although Ava believed that two of these photographs were taken at the same studio given that they have the same set, back drop, and chair, she concluded that they were not taken at the same time. She opined that they were both of the same child, possibly James Seligman, Bernard and Frances’ older son who was born in 1868 in Philadelphia. She thought the photo on the upper right could be James at three or four and the photo on the lower right James at six or seven.

The baby in the first photograph cannot be James Seligman since he was born in 1868 in Philadelphia before the family moved to Santa Fe. Thus, that baby has to be Arthur Seligman—if it is of one of the children of Bernard and Frances Seligman—as he was the only child of theirs born in Santa Fe, and he was in fact born in 1871, the year that Ava dated the photograph. Perhaps one of the other photographs is of James or perhaps is Arthur as he grew older.

I can see by looking at the coloring on the reverse of these three photos that they might have been taken years apart as they have faded in different ways. (It’s hard to see in the scan below, but they were slightly different shades.) But nevertheless, I can’t imagine why Frances and Bernard would have three photographs of one of their three living children and none of the other two—including my great-grandmother Eva Seligman Cohen, their oldest child. I was so disappointed that there was no photograph of her.

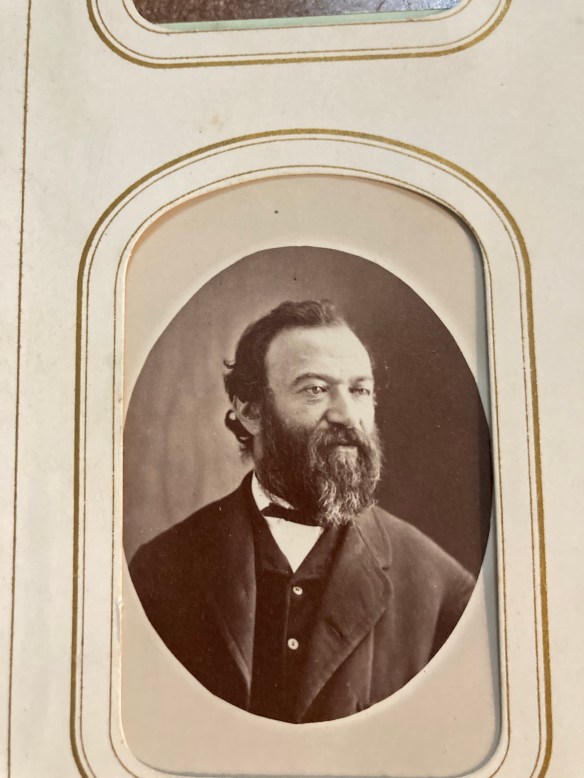

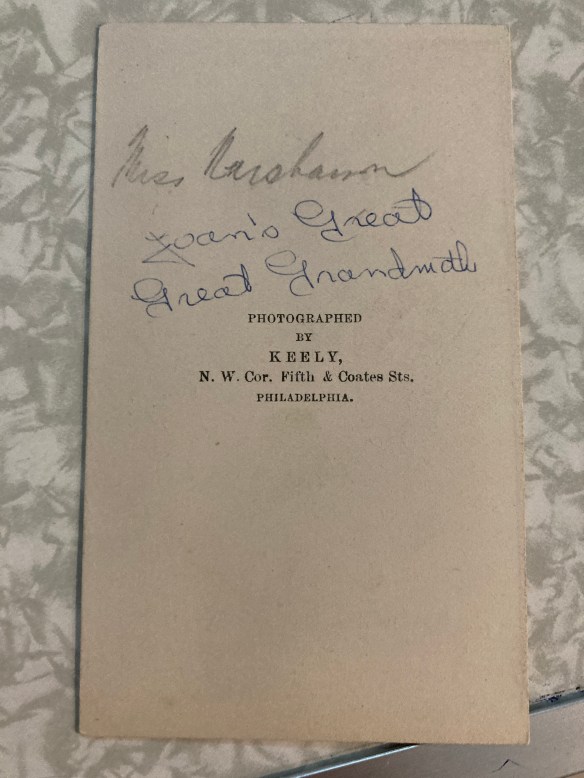

Moving on to the two men photographed in Santa Fe, the one on the same page as the three children (or the three photographs of the one child) was taken by a different Santa Fe photographer, Dr. Enos Andrews (1833-1910). Ava wrote that Andrews had a photography studio in Santa Fe from the end of the 1860s until the early 1870s. Based on her analysis of Santa Fe directory and census listings for Enos Andrews and other factors, Ava concluded this photograph was taken sometime between 1866 and 1871. Since she estimated that the man was about fifty years old, that would mean he was born between 1816 and 1821.2

But who was he? Although the birth year might led me to believe it was John Nusbaum, who was born in 1818, Ava pointed out that in the late 1860s, John (as well as Frances and Bernard until at least 1868) was living in Philadelphia. But it was possible that John went to Santa Fe and had his photograph taken there. After comparing this photograph with the one we thought could be John Nusbaum on the first page, Ava and I both thought it could be the same man and both could be my three-times great-grandfather John Nusbaum.

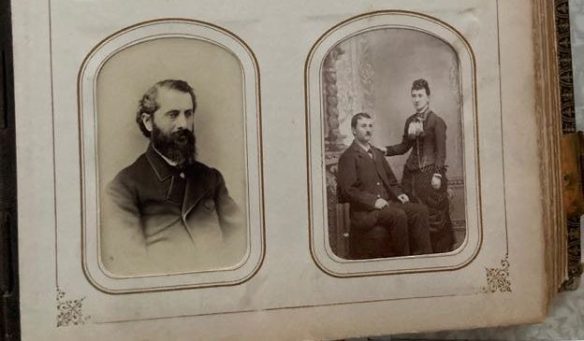

What about the other photograph of a man taken in Santa Fe on the following page? That photo was taken by Nicholas Brown, who once partnered with Enos Andrews. Ava provided the following background on Nicholas Brown and his son William Henry Brown, who took the photograph of the couple on the same page.

Nicholas Brown (born 1830) was the father of William Henry Brown. Nicholas was active in Santa Fe in 1864-1865. In August of 1866, Nicholas announced the opening of a studio with his son, William. Between 1866 and 1867, William was in partnership with his father in Santa Fe and they advertised the studio as N. Brown & Son and N. Brown E Hijo (1860s in Mexico). At the end of 1870, William was in Mexico. At the beginning of 1871, Nicholas re-opened his studio in Santa Fe but this time it was located on West Side Plaza. Because there is no address on [the reverse of the Nicholas Brown photograph of the bearded man], I am placing this image before 1871.3

Ava dated this photograph as 1866-1867 and estimated the man’s age as 45 to 50, meaning he was born between 1816 and 1822.

I could speculate that maybe this is Bernard’s brother Sigmund Seligman, who lived in Santa Fe from at least 1860 until his death in 1874. Sigmund was born in 1829, so later than the 1816-1821 time frame Ava posited. Could this man be younger than fifty? Could he be in his forties? The beard does make it hard to tell. But it’s possible. So could this be Sigmund? Maybe. Maybe not. I have no idea. Maybe he was a friend of Bernard’s, not his brother. I have no way to know.

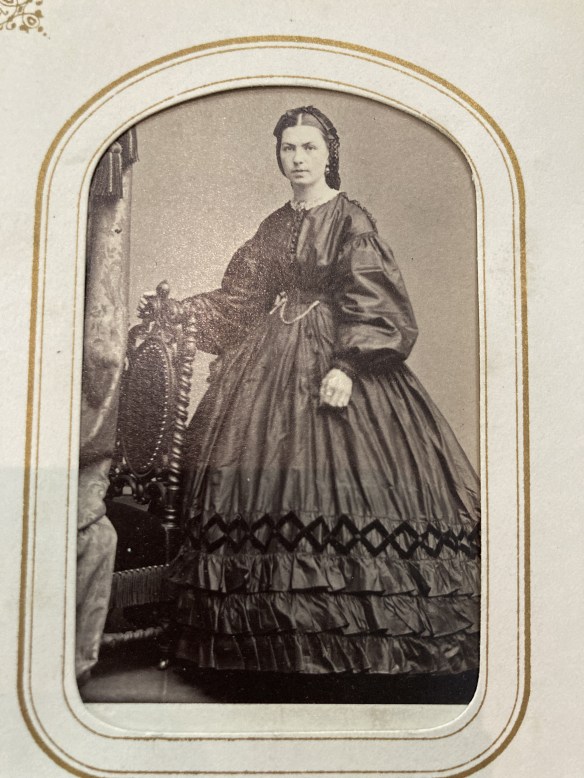

Finally, the last photograph from Santa Fe is the one of the couple taken by Nicholas Brown’s son, William Henry Brown. Ava dated this photograph far later than the one taken by Nicholas Brown because William was a partner in his father’s studio in Santa Fe from 1866-1867. By 1870, he was in Mexico. Then he returned to Santa Fe between 1880 and 1884 where he was a partner with George C. Bennett in a photographer studio on West Side Plaza. After 1884 William Henry Brown was no longer living or working in Santa Fe. Based on these facts, Ava dated this photograph at about 1882-1883.4

Ava thought that both the man and the woman were somewhere between 25 and 30 years old, meaning they were born between roughly 1852 and 1858, making them too young to be Bernard and Frances, who were born in 1838 and 1845, respectively. Thus, I have no idea who they are.

The fact that I could not identify the people in these Santa Fe photographs was disappointing. Ava reminded me again about the nature of CDVs—literally, “cartes de visite” or visiting cards. People gave them away, for example, when they came for a visit. And maybe they were taken while visiting and not in their hometown. That meant even those taken in Santa Fe or Philadelphia or elsewhere could be of people who didn’t live in those places. That meant the universe of people who might be in these photographs was anyone who lived during this time period. No wonder we couldn’t identify anyone with any degree of certainty without known photos of them.

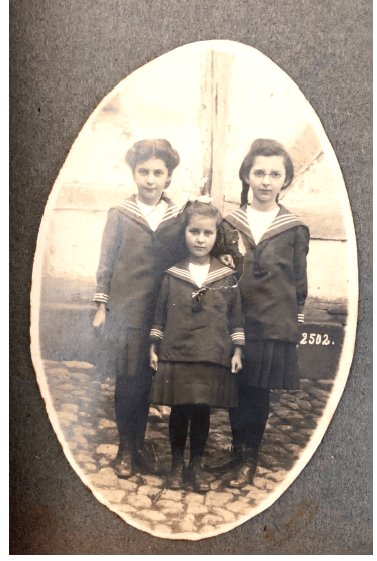

The last portion of Ava’s work on this project was devoted to trying to identify the people in some of the photographs taken in Bingen and Mainz, Germany.