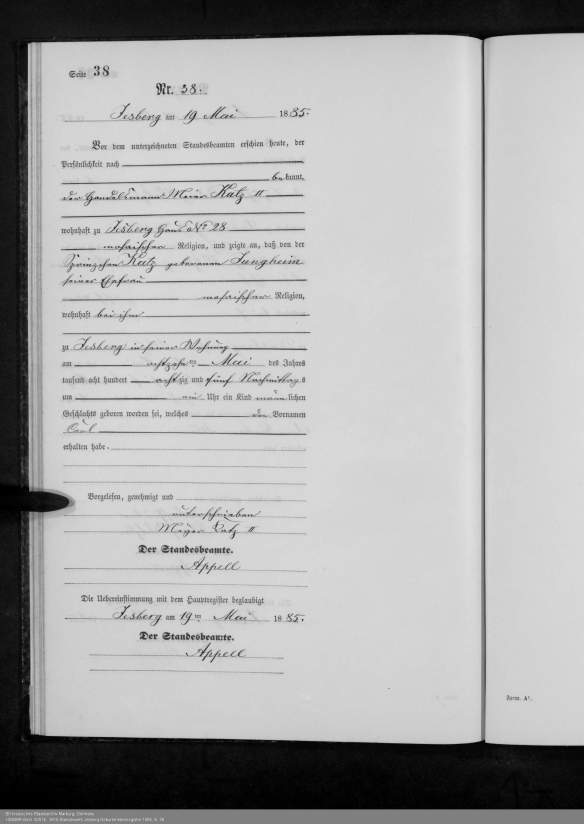

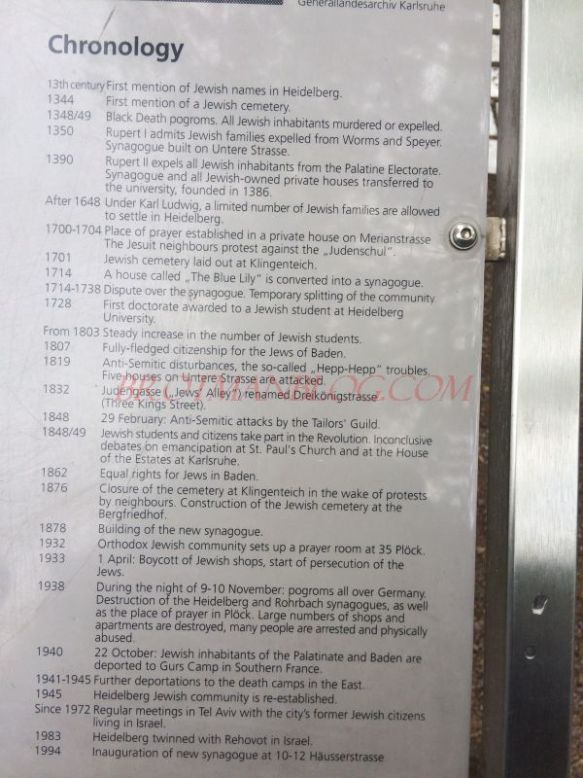

When Hitler came to power in 1933, three of the five children of Meier Katz and Sprinzchen Jungheim were still living in Germany: Aron, Regina, and Karl. Through the moving memoir of Fred Katz and the oral history of Walter Katz, we’ve seen how Karl Katz and his family were finally able to leave Jesberg by December, 1938. His sons Walter and Max had left earlier, and Karl, his wife Jettchen, and youngest son Fred left soon after Kristallnacht. All had settled in Stillwater, Oklahoma, with the help of Karl’s oldest brother, Jake.

Jake wasn’t only helpful to Karl’s family. Karl and his family had been preceded by his sister Regina and her family—her husband Nathan Goldenberg and their three children, Bernice, Theo and Albert.

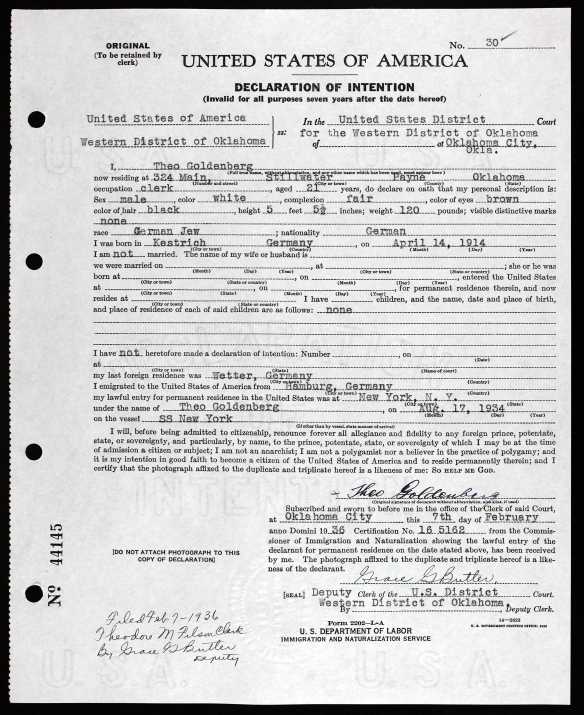

Theo was the first of Regina and Nathan’s family to leave Germany, arriving in New York on August 17, 1934, when he was twenty years old. Thanks to Theo’s granddaughter Abbi, I have some documents that reflect Theo’s work history and reputation before he left Germany. Special thanks to Doris Strohmenger and Heike Keohane of the German Genealogy group on Facebook for translating these documents for me.

This first letter, written November 14, 1932, when Theo was eighteen, is from his employer, A. Bachenheimer, a clothing manufacturing company, where Theo had been first an apprentice and then a salesman; he’d started when he was fourteen years old. The letter describes him as an honest, efficient and diligent salesman.

The second letter is from the next employer, Josef Volk, another clothing manufacturer, where Theo worked from December, 1932, until July 1933; this letter also describes him as willing, honest, and industrious. I am not sure where Theo went next or why he left this company, but given that Hitler had been elected by then and the boycott of Jewish businesses had been declared in April 1933, I assume there was some connection.

Theo left Germany a little over a year later. He filed a certificate of deregistration with the community of Kestrich on August 6, 1934, indicating that he was leaving the community.

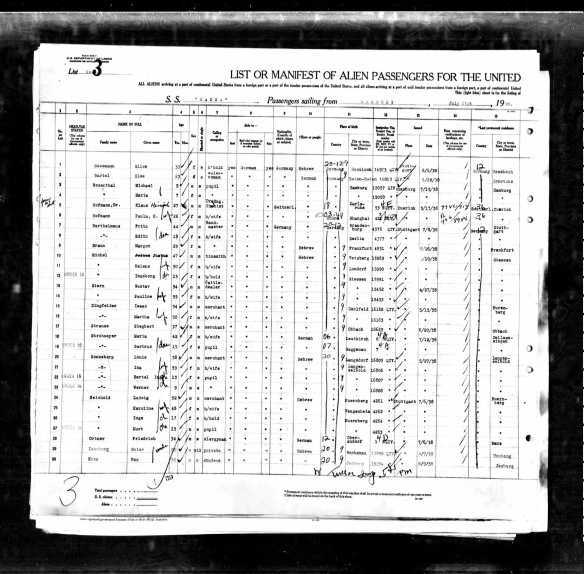

He sailed on the SS New York with his cousin, Helma Goldenberg, who was 22 and a nurse. Theo listed his occupation as “clerk” and his final destination as Stillwater, Oklahoma, where he was going to his uncle Jake Katz. (Helma was going to Georg Goldenberg, her uncle, who was in New York City.) As my cousin Marsha learned when she interviewed Theo in 1993, Jake met Theo at the boat in New York when he arrived and provided him with land to farm when they returned to Oklahoma. Theo told Marsha he “owed it all to Jake.”

Theo Goldenberg ship manifest, line 19, Year: 1934; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Microfilm Roll: Roll 5531; Line: 1; Page Number: 39

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957

Theo’s sister Bernice and her family were the next to arrive in the US. Bernice was married to Julius Katz, who was born in Steinbach, Germany. They had a son Henry. I knew that the family had arrived by 1940 because they are listed as living in Brooklyn on the 1940 census. Julius was working as a wholesale butcher, and Bernice as a dressmaker. But I could not find a passenger manifest for them. When I look back on it, I am not sure why it was so hard to locate. But I thought it might be worthwhile sharing what I did and how I finally found them.

Because all I had was the 1940 census, I used the names and ages on that census to search for a manifest. I searched for Bernice Katz, Julius Katz, Henry Katz, and Julius’ mother and sister, Violet and Bette Katz. I searched for any ship arriving between 1935 and 1940 because I knew from the census that they were still in Germany in 1935. But nothing came up that seemed right.

Bernice Goldenberg and Julius Katz and family, 1940 census, Year: 1940; Census Place: New York, Kings, New York; Roll: T627_2611; Page: 8A; Enumeration District: 24-2457

Then I searched to see if I could find more specific information about Julius and his mother and sister—when and where were they born? Nothing came up. Finally, I searched for obituaries, and although I found a SSDI record showing that Bernice had died in Fairfield, Connecticut in 1985, I could not find any obituaries. I was stumped.

So I decided to ask the family for help. I sent Theo’s son Nate a message on Facebook, asking whether he knew when Bernice had arrived and whether her son Henry was still alive. Nate knew that Henry had died within the last few years so I narrowed my obituary search to the last few years, and Henry’s obituary immediately appeared. It revealed, among other things, that Henry and his family had arrived in 1936. It also revealed that Henry was born in 1931, not 1933, as the 1940 census had indicated. (Hartford Courant, January 17, 2015)

That led me to a specific search for any Katz arriving in 1936 in New York City—with no limits on ages or names. And this time the search immediately produced the right result: a ship manifest for Julius Katz, Berni Katz, Heinz [Henry] Katz, Veilchen [Violet] Katz, and Betty Katz arriving in New York on April 10, 1936. Julius Katz listed his occupation as an animal dealer, and they were all heading to New York City where Julius’ brother Leopold Katz was living.

Bernice Goldenberg Katz and family on ship manifest, lines 9-13, Year: 1936; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Microfilm Roll: Roll 5787; Line: 1; Page Number: 176

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957

How had I missed this before? I am not sure. Yes, all the ages were off. Julius is listed as 37 on the 1936 manifest, but is listed as 48 four years later on the 1940 census; Bernice, who is listed as 29 on the manifest, is lasted as 37 on the 1940 census. Henry, as noted, was two years younger on the census than he was on the ship manifest. Had I searched too narrowly by those birth years? I don’t know. All I know is that I was very grateful to my cousin Nate for providing me with enough information to narrow my search and find the passenger manifest for his aunt Bernice and her family.

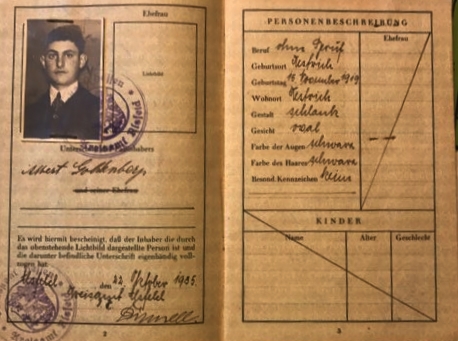

On July 2, 1936, less than three months after Bernice and her family arrived, Nathan and Regina (Katz) Goldenberg and their son Albert arrived from Germany. (Regina is listed as Rosa here.) Nathan’s occupation was a cattle dealer, and Albert, who was sixteen, was an apprentice. Here is Nathan’s business identification card from Germany:

They were headed to Stillwater, Oklahoma, going to Jake Katz and also joining their son Theo.

Nathan Goldenberg and family, ship manifest, lines 1-3, Year: 1936; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Microfilm Roll: Roll 5825; Line: 1; Page Number: 20

Description

Ship or Roll Number : Roll 5825

Source Information

Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957

Here are their German passports:

In 1940, Nathan, Regina, Theo, and Albert were all living together in Stillwater where Nathan and Albert were farming, and Theo was a salesman in a clothing store—Katz Department Store in Stillwater.

Nathan Goldenberg and family, 1940 census, Year: 1940; Census Place: Stillwater, Payne, Oklahoma; Roll: T627_3323; Page: 19A; Enumeration District: 60-33

Description

Thus, the entire family of Nathan and Regina (Katz) Goldenberg had safely left Germany before 1940.. Theo filed a Declaration of Intent to become a US citizen on February 7, 1936, his brother filed on February 10, 1938, his father Nathan filed one on December 29, 1938, and his mother Regina had done the same on August 18, 1941. All must have been very relieved to be safely living in Stillwater and anxious to become American citizens.

Theo Goldenberg Declaration of Intent

National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.; ARC Title: Petitions 1932 – 1991; ARC Number: 731222; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States; Record Group Number: 21

Oklahoma City Petitions, 1954-1957 (Box 6; Volume 14-17)

Ancestry.com. Oklahoma, Naturalization Records, 1889-1991

Albert Goldenberg Declaration of Intent

National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.; ARC Title: Declarations of Intention for Citizenship , compiled 1908 – 1932; ARC Number: 731206; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States; Record Group Number: 21

Oklahoma City Declarations of Intention, 1932-1974 (Box 1)

Ancestry.com. Oklahoma, Naturalization Records, 1889-1991

Nathan Goldenberg Declaration of Intention

National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.; ARC Title: Declarations of Intention for Citizenship , compiled 1908 – 1932; ARC Number: 731206; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States; Record Group Number: 21

Oklahoma City Declarations of Intention, 1932-1974 (Box 2)

Ancestry.com. Oklahoma, Naturalization Records, 1889-1991

Regina Katz Goldenberg Declaration of Intent

National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.; ARC Title: Declarations of Intention for Citizenship , compiled 1908 – 1932; ARC Number: 731206; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States; Record Group Number: 21

Oklahoma City Declarations of Intention, 1932-1974 (Box 2)

Ancestry.com. Oklahoma, Naturalization Records, 1889-1991

Albert and Theo both registered for the draft, Theo on October 16, 1940, and Albert on July 1, 1941. Both were working at Katz Department Store in Stillwater at the time of their registrations.

Theo Goldenberg draft registration

Page 1 – Selective Service Registration Cards, World War II: Multiple Registrations 1940

Web Address

http://www.fold3.com/image/612584757?xid=1945

Albert Goldenberg draft card

Page 1 – Selective Service Registration Cards, World War II: Multiple Registrations 1941

Web Address

http://www.fold3.com/image/612584753?xid=1945

Tragically, the family was to suffer two terrible losses not that long after settling in the United States. First, on March 17, 1944, Nathan Goldenberg died. He was only 67 years old. According to his obituary, he had been ill for some time. His two sons were in the military at the time of his death; Theo was a corporal in the US Army stationed in Garden City, Kansas, and Albert was a private, first class, stationed in the Pacific Theater. “Goldenberg Rites Sunday,” Stillwater Newspress, March 17, 1944, p.3.

Just three months later on July 12, 1944, Albert was killed in action serving his adopted country. According to his obituary, he had been inducted into the army on December 1, 1941, just six days before Pearl Harbor. He had trained at Camp Barkley in Texas and was serving with the medical corps attached to the 105th Infantry in Saipan when he was killed. He was only 24 years old at the time of his death. “Services Set for Goldenberg, Stillwater Newspress, June 16, 1948, p. 8.

According to Theo’s son, after receiving training to join the intelligence service, Theo was en route to France when he received word that his brother had been killed; he was called back and discharged from the service as the sole surviving son. In the space of three months, Regina Katz Goldenberg had lost her husband and her youngest child, and her two remaining children, Theo and Bernice, had lost their father and younger brother. How heartbreaking it must have been to have escaped the Nazis only to lose two family members so soon afterwards, one of whom was killed serving his new country.

After returning home to Stillwater, Theo returned to work at Katz Department Store with his uncle Jake, where he worked for over fifty years, and also operated a small dairy business for over forty years. He milked cows by hand and sold raw milk; he was the last dairyman to be able to sell raw milk in Payne County.

On October 15, 1950, Theo married Anne Marie Kunstler, who was born in Nuremburg, Germany. They were married in Stillwater.

Marriage License of Theo Goldenberg and Anne Marie Kunstler

Ancestry.com. Oklahoma, County Marriages, 1890-1995 [database on-line].

Original data: Marriage Records. Oklahoma Marriages. FamilySearch, Salt Lake City, UT.

Apparently Oklahoma met her standards, and she and Theo were married for almost fifty years. Theo died on January 11, 2000. He was 86 years old. Anne Marie is still living.

As for Theo’s sister Bernice, she and her husband Julius and their son Henry lived in Brooklyn for many years, where Julius worked in the meat industry (a kosher hot dog company) and Bernice in the garment district. She would take her sewing machine back and forth from work so that she could work at home in the evenings. Bernice and Julius moved to Fairfield, Connecticut, in 1975, after Julius was mugged several times in Brooklyn.

Julius Katz died on November 26, 1977, in Fairfield. Bernice Goldenberg Katz, died at age 79 in Fairfield, Connecticut, on May 2, 1985. Their son Henry died on January 15, 2015, in West Hartford, Connecticut. He was a veteran of the Korean War and was a structural designer, having studied at Pratt Institute and New York City Community College. He worked for over thirty years at Dorr Oliver, a chemical engineering company in Stamford, Connecticut. (Obituary, Henry Herman “Hank” Katz, The Hartford Courant, January 17, 2015.)

Thus, another branch in the family of Meier Katz and Sprinzchen Jungheim survived the Holocaust and prospered in America. But for the tragic death during World War II of young Albert Goldenberg, this would have been another happy story about Meier and Sprinzchen’s descendants.