As many of you know, I have not had much success using DNA as a genealogy research tool. Because I have thousands of matches on each of the major DNA testing sites (Ancestry, 23andme, FamilyTreeDNA, and MyHeritage), finding a true match—not one just based on endogamy—is like looking for a needle in a haystack. Over time I have found some “real” matches, but I usually only know they’re real because I’ve already found those cousins through traditional genealogical research. Finding that the DNA confirms what I already knew is nice, but not really helpful in terms of advancing my research. Even when I look at the matches that cousin shares with me, I am not making progress because our shared matches also number in the hundreds if not thousands.

Nevertheless, I periodically check my matches on each of the sites to see if any truly close matches have appeared. A couple of weeks ago I checked with 23andme and discovered a new third cousin match, Alyce, who also shared a family surname that appears on my tree—Goldfarb. Since the Goldfarbs are related to my Brotman line, I was quite excited. My Brotman line is one of my biggest brickwalls. I cannot get beyond the names of my great-great-grandparents.

Some background: my maternal grandmother’s parents were Joseph Brotman and Bessie Brod. But sometimes Joseph’s surname is listed as Brod, sometimes Bessie’s is listed as Brotman. Family lore is that Bessie, Joseph’s second wife, was his first cousin. Various US records revealed that Joseph’s parents were Abraham Brotman and maybe Yette Sadie Burstein; Bessie’s parents were Joseph Brod and Gittel Schwartz. But I have no records from Poland where they once lived to verify those names, nor can I get any further back to determine if Joseph and Bessie were in fact first cousins.

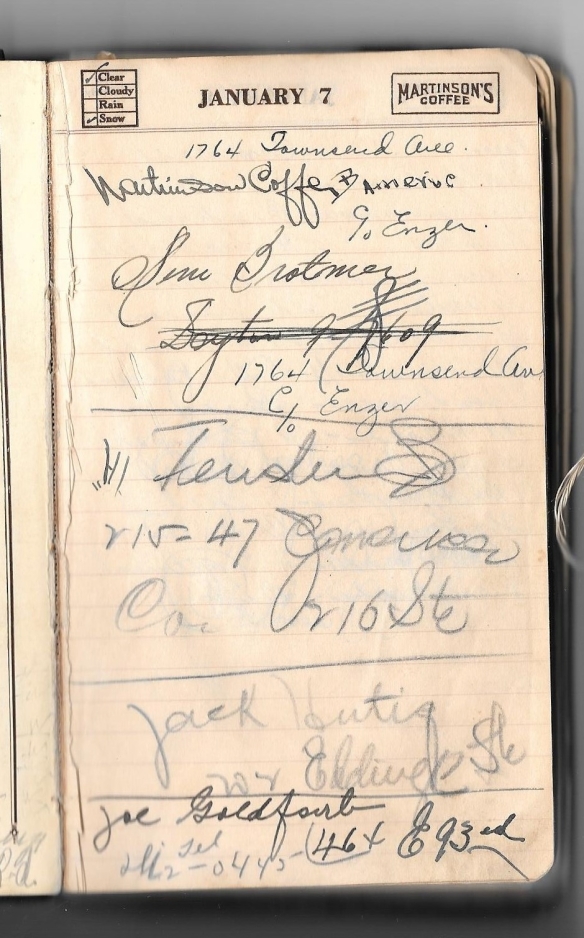

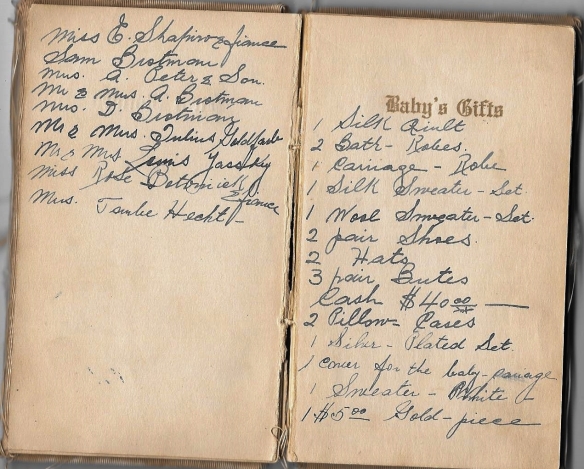

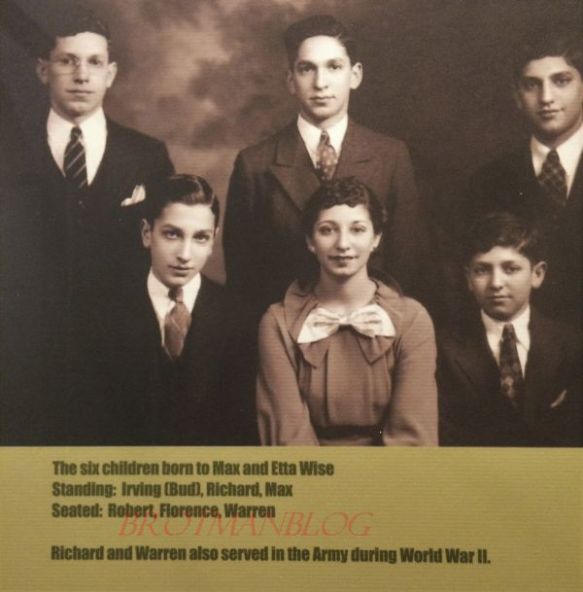

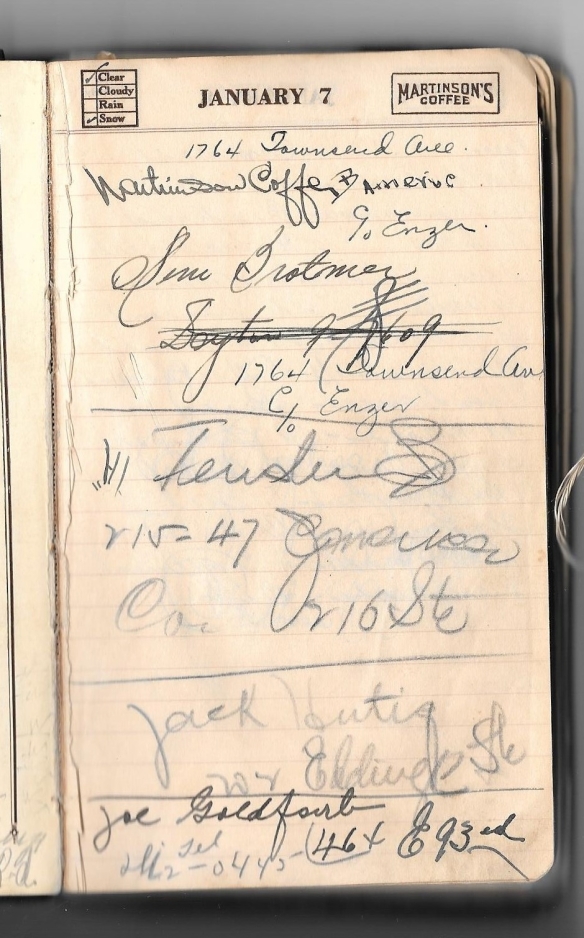

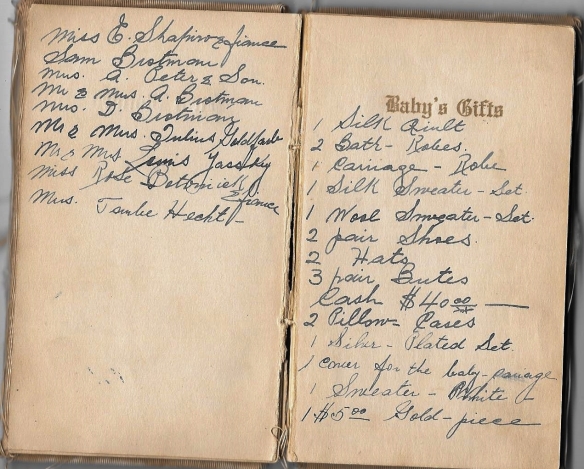

Then years later I discovered the Goldfarb cousins after seeing the names Joe and Julius Goldfarb and Taube Hecht in my grandfather’s address book and my aunt’s baby book.

After much digging, I learned that my great-grandmother Bessie Brod had a sister Sarah Brod (or Brotman) who married Sam Goldfarb. Joe and Julius Goldfarb were two of their sons, my grandmother’s first cousins. And Taube Hecht was my grandmother’s half-sister Taube Brotman, daughter of Joseph Brotman and his first wife. Taube’s daughter Ida had married Julius Goldfarb.

Through more research I was able to locate cousins descended from the Goldfarb line and from the Hecht line—Sue, a granddaughter of Julius Goldfarb and Ida Hecht, and Jan, a descendant of Taube Brotman Hecht line through her son Harry. They tested, but the results didn’t help me advance my research. I still couldn’t determine if my great-grandparents were in fact first cousins, and I still hadn’t found anything to expand the reach of my Brotman/Brod family tree.

Then a few weeks ago I found Alyce, a granddaughter of Joe Goldfarb and his wife Betty Amer and thus a pure Goldfarb (non-Hecht) cousin. She connected me with a few other Goldfarb cousins—descendants of Joe or one of his siblings. That’s a lot more DNA to work with, and I am hoping that I can get someone who’s more expert at parsing these things to help me use the DNA of these new cousins to advance my research. So far all I can do is stare at chromosome browsers and see overlaps, but I have no idea how to parse out the Goldfarb (Brod) DNA from the Hecht (Brotman) DNA to get any answers.

All of this I will return to at some point when I have more to say about what the DNA reveals. For now I want to talk about the photographs that Alyce shared with me of my Goldfarb relatives. Alyce sent me over twenty photographs. She was able to identify the people in many of them, but unfortunately a number are unlabeled. Also the quality of some of the photos is quite poor. I won’t post them all, but I will post a few today and more in a later post.

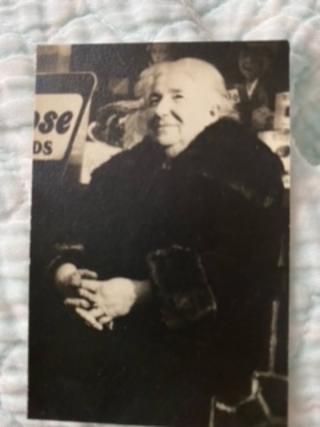

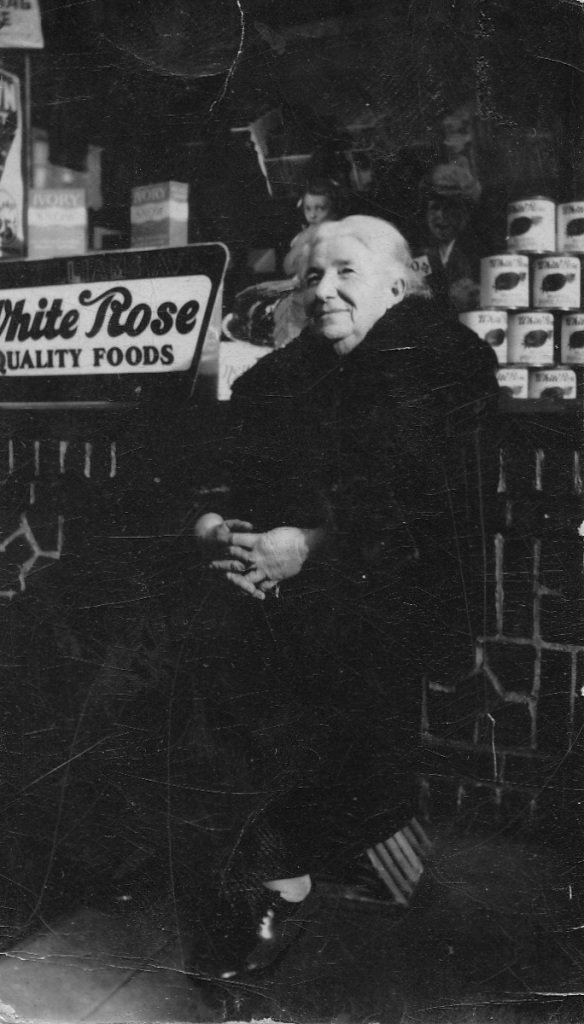

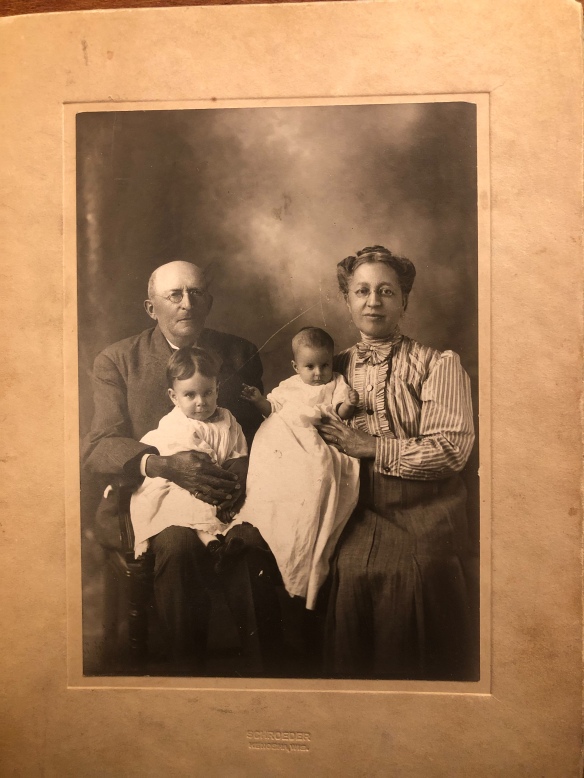

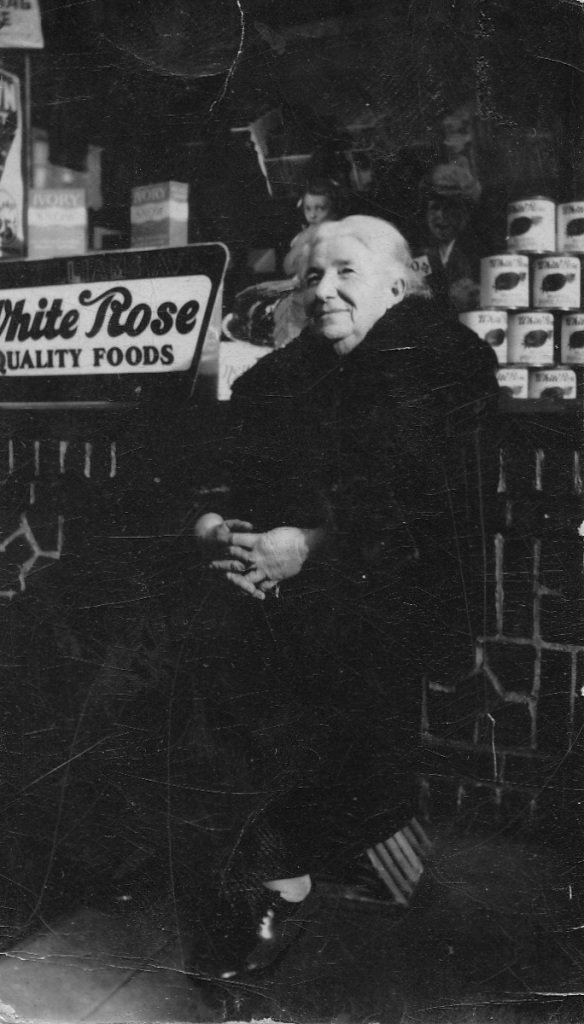

First, in Alyce’s collection was this photograph she labeled “I think this is Grandpa’s mother Sarah Brothman. I could be wrong.” (Brothman was yet another variation on how Joseph, Bessie, and Sarah spelled their surname.)

“Sarah Brothman” Courtesy of Alyce Shapiro Kunstadt

I almost fell off my chair. I had that exact same photograph, but in our collection the photograph was said to be of my great-grandmother Bessie Brod Brotman.

My great-grandmother Bessie Brotman (or so I was told)

I wasn’t sure who had the right label for the photograph, but just the fact that Alyce and I had in our possession copies of the same photograph seemed to confirm what the DNA and all my research had already told me—we were cousins!

Alyce had other photographs of her great-grandmother Sarah, and when I saw those I thought that in fact that first photograph was of Sarah, not Bessie. Here are her other photographs of Sarah, all courtesy of Alyce, and then another photograph I had of my great-grandmother Bessie.

Sarah Brod/Brotman Goldfarb and her son Leo Goldfarb. Courtesy of Alyce Shapiro Kunstadt

Bessie Brotman

Bessie Brotman

It seems to me that Bessie had a rounder and softer edged face than the woman seated in front of the grocery store, so I think that woman was indeed Sarah, Bessie’s sister.

So somehow my family ended up with a photograph of Bessie’s sister Sarah. And we never would have known if I hadn’t found Alyce and she hadn’t shared her copy of the photograph.

I slowly flipped through the rest of Alyce’s photos, noting the faces of my grandmother’s Goldfarb first cousins Joe and Leo and their wives and children, hoping I could identify some of the unknowns in Alyce’s collection, when I came to this photograph. This time my jaw dropped.

Alyce labeled this photograph, “Grandpa Joe. I think that could be Aunt Rose [the youngest child of Sarah Brod and Sam Goldfarb] on the left. Not sure who’s on the right.”

But I knew who was on the right. I had no doubt. That woman was my grandmother, Gussie Brotman Goldschlager, posing with two of her first cousins, Joe and Rose Goldfarb. I was blown away. How could Alyce, who until just a few days earlier was unknown to me, have a photograph of my grandmother—a photograph I’d never seen before?

I sent the photograph to my brother for confirmation, and he agreed. I ran the photograph through Google’s face identification software, and Google agreed. Here are some other photographs of my grandmother.

Gussie Brotman

Goldschlagers 1935

Jeff and Gussie c. 1946

I think you also will agree. Alyce, my third cousin, had a photograph of her grandfather Joe and my grandmother Gussie together. Wow.