I am back from a break after a great visit with our kids and then a week to recover! Before I return to the story of the family of Malchen Rothschild (as I am still waiting to speak with her great-grandson Julio), I have an update about how I discovered my great-great-grandmother’s will.

Earlier this summer Teresa of Writing My Past wrote about full-text searching on FamilySearch. I had never known about this tool but was tempted to see what I could find. I followed the link that Teresa provided on her blog and entered “John Nusbaum Cohen” to see what would come up.

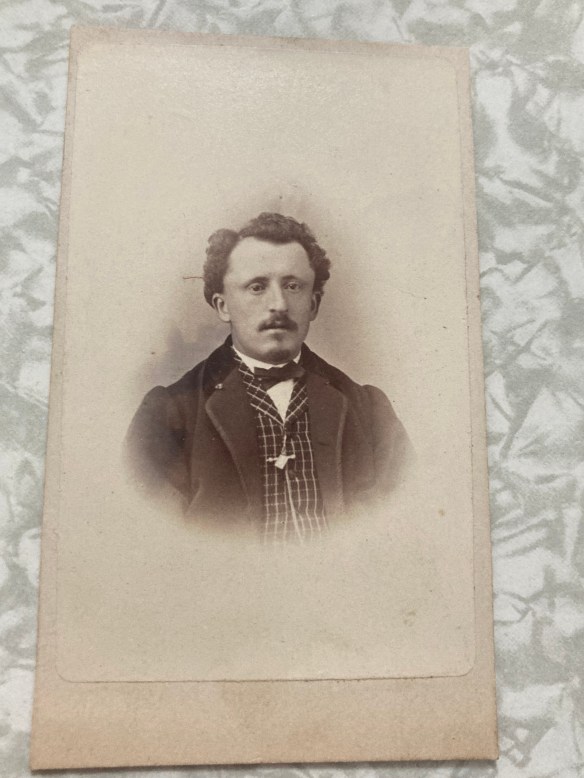

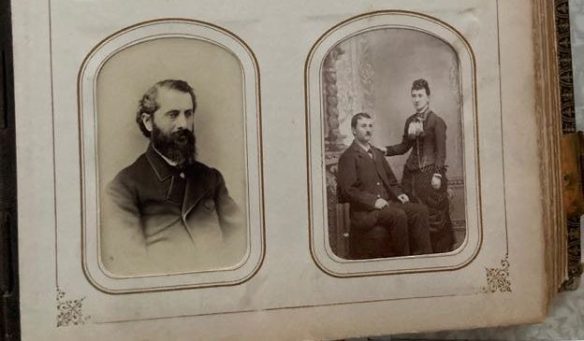

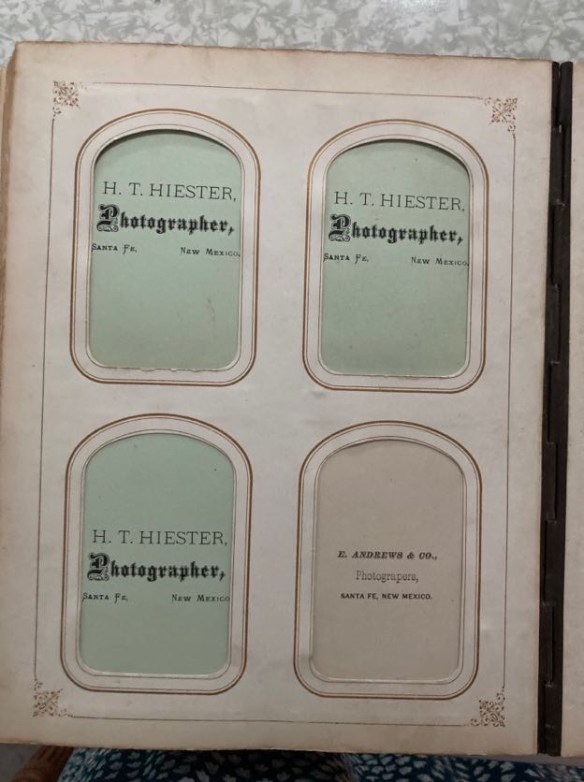

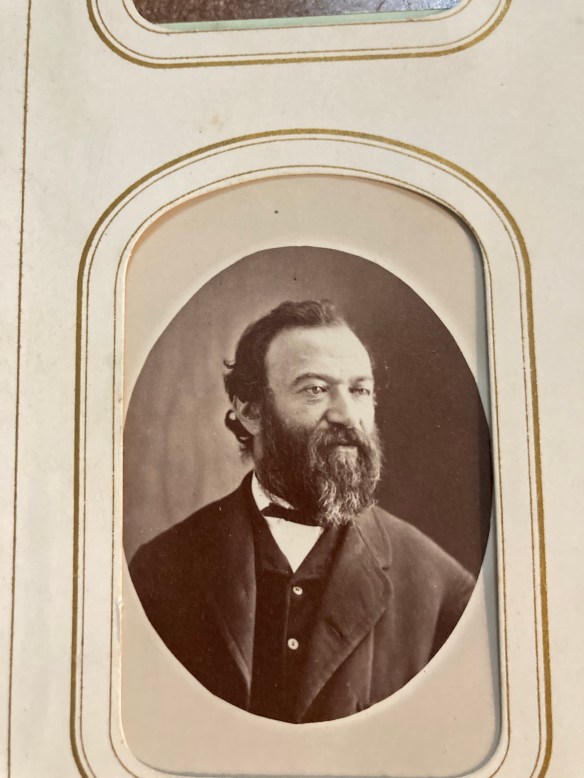

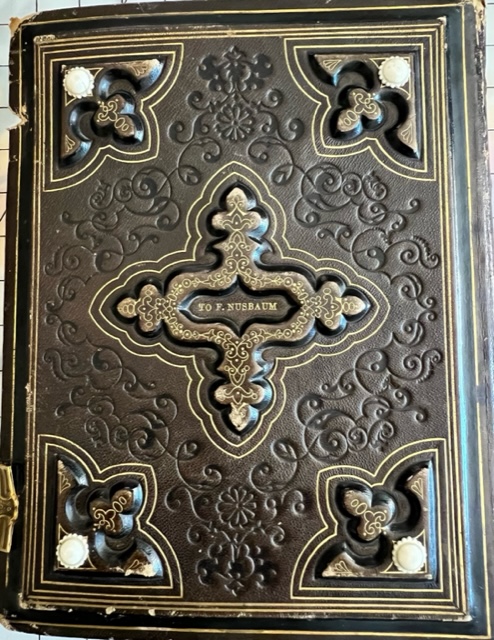

Lo and behold, it immediately retrieved what turned out to be the last will and testament of my great-great-grandmother Frances Nusbaum Seligman. Frances was the daughter of John Nusbaum, my three-times great-grandfather, and the wife of Bernard Seligman, my great-great-grandfather—-two of my pioneer ancestors who came to the US as young men from Germany in the mid-19th century. Both John Nusbaum and Bernard Seligman became successful merchants, John in Philadelphia and Bernard in Santa Fe. But neither came here as a wealthy man.

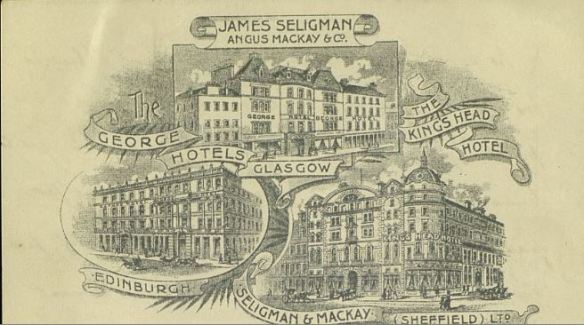

So I was amazed when I read this will to see just how much property—-jewelry, cash, and other property—Frances owned at the time of her death in Philadelphia on July 27, 1905. She was only 59 when she died, and she left behind three surviving children (two had died before adulthood): my great-grandmother Eva Seligman Cohen and her brothers James Seligman and Arthur Seligman. In addition, Frances had siblings and grandchildren, all of whom are named in her will, as well as other family members and friends.

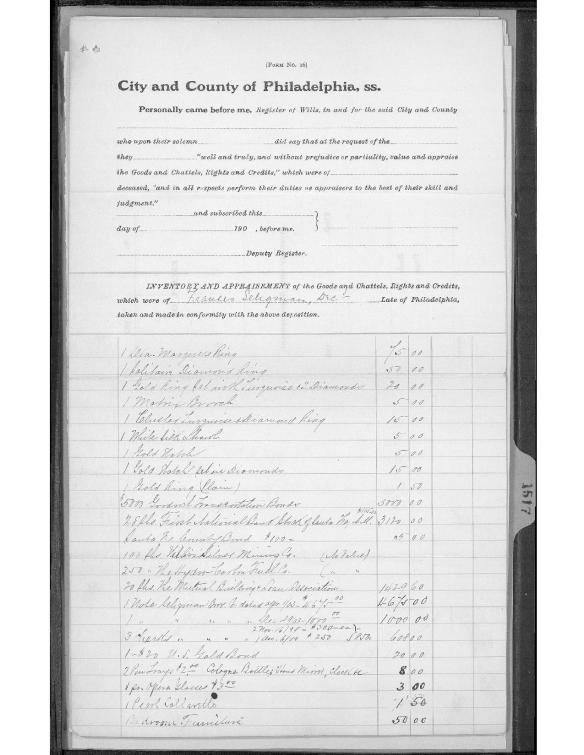

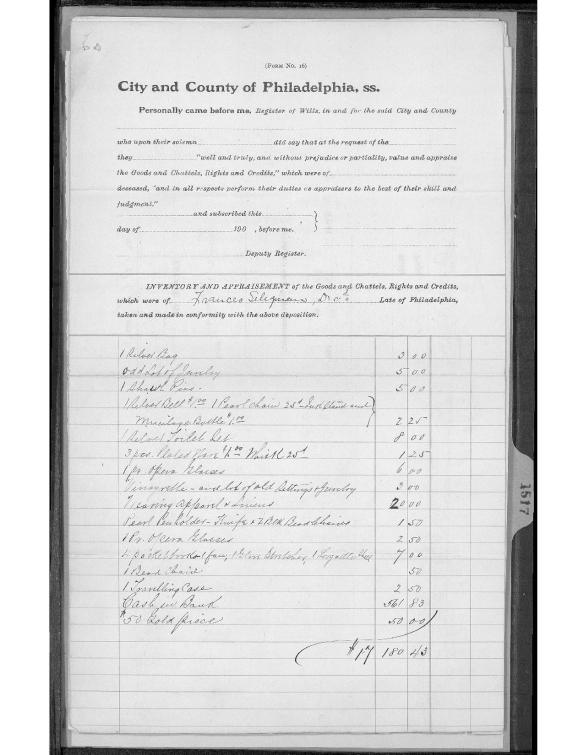

There were two inventories of Frances’ property. The bulk of her property was inventoried in September 1905 and included stock, cash, jewelry, and other personal items.1

The total value of these properties came to $17,180.43, or approximately $617,000 in today’s dollars. Of course, many of these items, especially the jewelry, may have appreciated far beyond the value they had in 1905 and beyond what the inflation calculators consider.

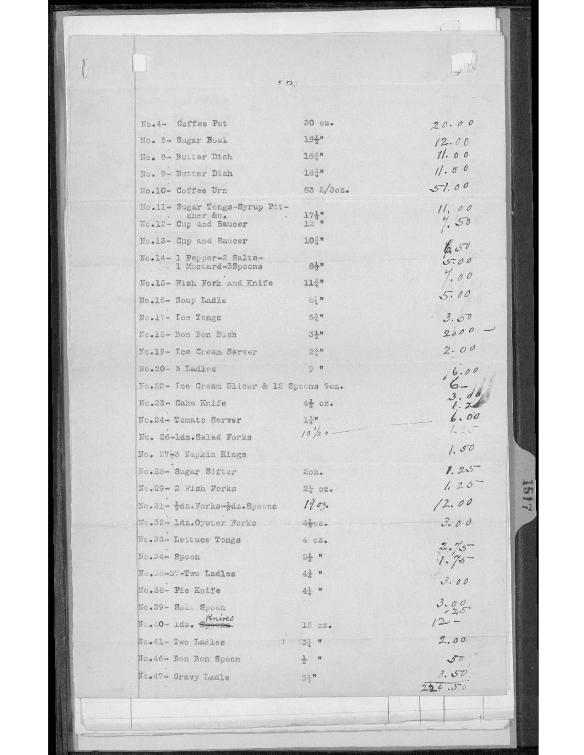

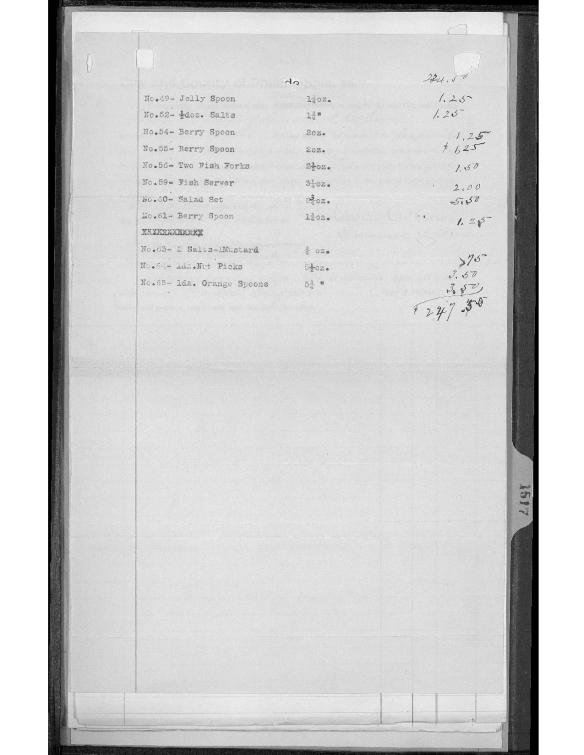

The second inventory was of Frances’ kitchenware and dishware:

The value of these goods was appraised in 1906 as $247.55. In today’s dollars that would be approximately $9000.

The documents do not include any appraisal of any real estate although, as we will see, Frances owned some real estate in Santa Fe.

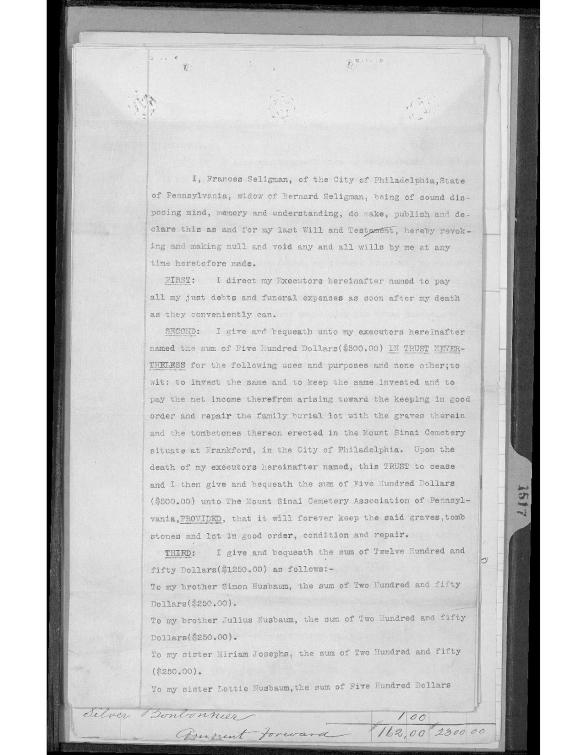

Frances’ will detailed with great specificity where all this personal and other property was to go. Her original will is eight typed pages plus there is a one page handwritten codicil. I loved reading this will because it names so many of the relatives I’ve written about on my blog. It was fascinating to see how inclusive Frances was in deciding who would get portions of her estate. The following images are the pages from the will with my comments about some or all of the provisions on that page.

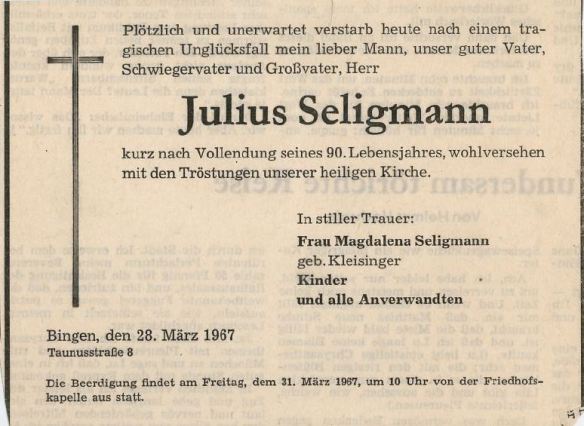

In the Third Clause below, Frances divided $1250 among her four siblings. But Simon, Julius, and Miriam each got $250 whereas Lottie received $500. Did she love Lottie more than the others? Or did Lottie have greater need? Lottie never married, so unlike Miriam who had a husband to support her and Simon and Julius who were men, Lottie may in fact have had greater need.

There is a similar seemingly favorable bias in terms of Frances’ distribution to her three living children, Eva, James, and Arthur. Eva was to receive all of her mother’s linen and wearing apparel. Well, I guess the sons couldn’t wear her clothes. But then in the Fifth Clause above, Frances bequeathed a whole lot of jewelry to Eva: “my diamond bracelet, my diamond star with chain attached thereto, my watch studded with diamonds, one of the large diamonds from my thirteen stone diamond ring, my set of silver containing one dozen knives, one dozen large spoons, one dozen small spoons, one large soup ladle and one dozen silver forks.”

What did James get? “One diamond from my thirteen stone diamond ring and a silver coffee pot.” And Arthur: “the other large diamond from my thirteen stone diamond ring, and a silver coffee pot.”

Wow, did they get shafted or what! Even Emanuel Cohen, my great-grandfather and Eva’s husband, got “the centre diamond in my diamond cluster pin.” And he was married to Eva, who was already getting all those diamonds!

Frances then gave other jewelry items to her daughters-in-law and to her grandchildren. My grandfather John Nusbaum Cohen got “four stones from my diamond cluster pin.”

The will goes on to identify specific pieces of jewelry for other family members—aunts, uncles, nephews, nieces, brothers-in-law, and even August Seligman, the younger brother of Bernard Seligman, a brother who never left Germany. Did August get the “silver knife, fork and spoon marked S.S.”? Perhaps his great-grandson Wolfgang knows. I will have to ask him.

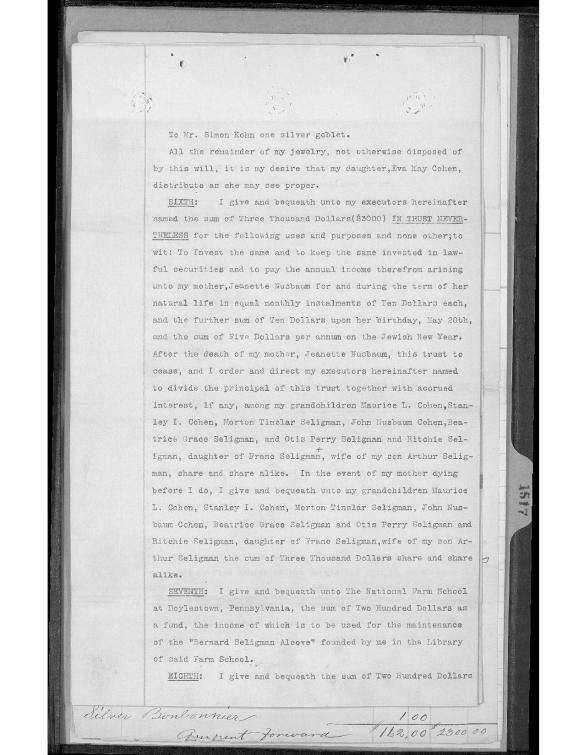

And then at the end of that Fifth Clause below, the will provides, “All the remainder of my jewelry, not otherwise disposed of by this will, it is my desire that my daughter, Eva May Cohen, distribute as she may see proper.”

Before I go on, I need to point out that I do not have one piece of jewelry or anything else that once belonged to Frances Nusbaum Seligman, my great-great-grandmother. Not one thing. Even though all those diamonds were bequeathed to my great-grandmother Eva Seligman Cohen, I have no idea where they went once Eva died. She raised my father and his sister from the time they were quite young when both their parents were hospitalized, yet my father did not have one thing—-not one spoon or even a coffee pot—-that had belonged to his beloved grandmother. I have no idea where it all went. Perhaps it was sold during the Depression. Perhaps the other three grandchildren of Eva Seligman Cohen received it, but that seems unlikely. In any event, it’s gone.

Having cleared the air on that, I am now looking at the Sixth Clause (see above). It provides in part for a $3000 trust for Frances’ mother Jeanette Dreyfus Nusbaum, my three-times great-grandmother, who was still living when Frances drew up this will in 1905. I love that Frances provided for her mother and even specified that she receive ten dollars on her birthday (May 20) and five dollars at the Jewish New Year in addition to the ten dollar regular monthly payments under this provision. It shows me how caring Frances was and also how much being Jewish was still an important part of the family’s life. Jeanette was 87 when the will was executed, and she outlived her daughter Frances, dying on January 12, 1908, at the age of 90.

There are then several bequests to various charitable organizations, and then we come to the Eleventh Clause (below), in which Frances requires that a trust be created from fifty shares of her stock in Seligman Brothers in Santa Fe, the dividends from which were to be paid to “my daughter Eva May Cohen, for and during her natural life, for her sole and separate use, not to be in any way or manner whatever liable to the contracts, debts, or engagements of her husband.” I am so impressed that Frances had the wisdom to set aside money that would be only for her daughter and not under the control of Eva’s husband. How progressive is that!

The provision further provides that Eva’s children would inherit that stock upon her death as well as Eva’s brothers James and Arthur. Sadly, Seligman Brothers itself did not survive long enough to benefit those beneficiaries as it closed for business by 1930.

Nevertheless, once again Frances favored Eva in the will.

The Twelfth Clause refers to a house and lot in Santa Fe to be shared by all three of Frances’ children. (I don’t see that property included in the inventories mentioned above so the estate was worth more than estimated above.) In 1904 when Frances executed this will that was the location of the oldest hotel in Santa Fe, the Exchange Hotel. I have no idea what it was worth at that time, but it certainly added something substantial to the overall value of Frances Nusbaum Seligman’s estate.

Below are the final provisions in the original will.

There is also a handwritten codicil to the will dated February 18, 1905. It includes additional specific bequests of various items of personal property and also provides that $200 was to be given to Congregation Keneseth Israel for the purpose of “placing the names of my husband Bernard Seligman and my own, together with the dates of our respective deaths, upon the memorial tablet on the North-East Wall of the Synagogue.” We all want to be remembered, don’t we?

I wrote to Congregation Keneseth Israel, now located in the suburbs of Philadelphia, asking about my great-great-grandparents’ plaque, and I was quite moved and relieved to learn that it still exists on their memorial wall in their suburban location. Their executive director Brian Rissinger kindly sent me this image of the plaques:

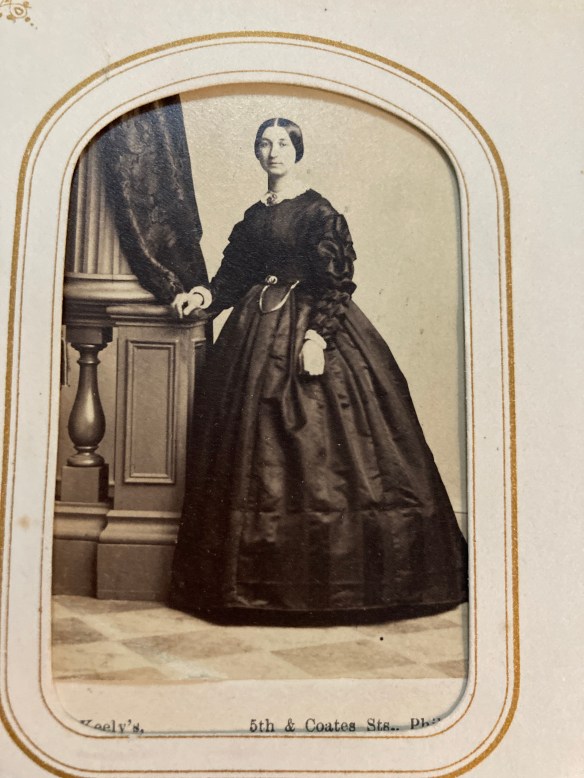

Finding this will was such a gift. It gave me insights into my great-great-grandmother Frances Nusbaum and her relationships with her children, grandchildren, siblings, and others. And it reminded me how extraordinary her life was—-growing up as the daughter of a successful merchant in Philadelphia only to fall in love with a young immigrant from Germany who had lived in Santa Fe. After marrying him and having four children in Philadelphia, she moved with him and their children to Santa Fe, living in what was then a small but growing pioneer town with very few Jews and even fewer Jewish women. And her will demonstrated that she cared deeply about her Jewish identity. She must have been so resilient and so devoted to make that adjustment to life in Santa Fe. I wrote about Frances and Bernard in my family history novel, Santa Fe Love Song for anyone who wants to know more about them..

Frances was described in her obituary in these terms:

“She was a beautiful and accomplished woman, as good as she was beautiful and as beautiful as she was good, and of a most lovable and gentle disposition. She was an exemplary wife, a fond and good mother, and a dutiful and loving daughter. Indeed she was all that is implied in the phrase ‘a thoroughly good and moral woman.’ … She will be especially remembered by the poor people of [Santa Fe], to whom she was particularly kind. Many and many truly charitable deeds have been put to her credit.”

Everything in her will reflected those same qualities.

I was deeply touched by the relationship between Frances and her daughter Eva, my great-grandmother. Frances had lost two daughters; her daughter Florence had died when she was just a month old, and her daughter Minnie had died when she was seventeen. Thus, Eva, her first born child, was her only surviving daughter, and that must have made Frances cherish her even more.

That Eva was deeply loved by her mother also sheds light on the woman she became. In learning about Eva from my father and from my research, I grew to appreciate what a strong and compassionate woman she was. Like her mother Frances, she lost one son as a baby and a second son predeceased her by committing suicide. Like her mother, Eva was uprooted from Philadelphia to Santa Fe, but returned to Philadelphia for college and lived the rest of her life there after marrying my great-grandfather Emanuel Cohen. Being so far from her parents and brothers back in Santa Fe must have been as difficult for her as it had been for her mother to leave her family behind in Philadelphia to move to Santa Fe.

Despite all those losses and difficulties, Eva clearly had a big heart. She took a widowed brother-in-law and his son into her home for many years, she took her parents into her home when they returned to Philadelphia to retire, and, most importantly to me, she took my father and aunt into her home and provided them with comfort, love, and security when their parents were unable to care for them.

The love between Frances and Eva, between mother and daughter, shines through in this will. And I am so grateful to Teresa for alerting me to the full-text search on FamilySearch so that I could find it.

-

All the documents included in this post were located using the full-text search on FamilySearch. They are cited there as follows: Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States records,” images,

FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-D4WP-CQ?

view=fullText : Aug 30, 2025), images 189-206 of 315. ↩