In my last post, I wrote about Erbes-Budesheim, the German town where my Schoenfeld ancestors lived, where my 3x-great-grandmother was born, and where my 4x- and 5x-great-grandparents lived. From the records I was able to obtain, I know that my 4x-great-grandparents Bernhard Schoenfeld and Rosina Goldmann were married and living in Erbes-Budesheim by 1804 when their first child Benedict Baehr was born.

As explained to me by Gerd Braun, the man in Erbes-Budesheim who sent me the documents, when the French took over control of the region, one thing that they did in 1808 was order the Jewish residents to adopt surnames akin to those used by the Christian population. Before that, Jews used patronymics. Thus, before 1808, Bernhard Schoenfeld was named Baer (ben) Salomon[1] and Rosina was Rosina (bat) Benjamin. The two children born before 1808 were named Benedict (ben) Baer and Taubchen (bat) Baer. Taubchen was renamed Eva Schoenfeld after 1808.

Here is the birth record for Benedict. (All the records before 1816 are in French, and my high school French classes came in handy.) The translations for all of the documents below are in italics.

Benedict Baer birth record 1804

Act of birth of Benedict Baer born the 15th of Frimaire[2] at 10 in the morning, the legitimate son of Baer Salomon, merchant, living in Erbesbudesheim, and of Rosine nee Benjamin of Munchweiler. The sex of the child has been recognized as masculine. [Witnesses and signatures]

Benedict died just eight months later.

Benedict Baer death record 1805

Act of death of Benedict Baer, died the 17th of Messidor[3] at 7 in the evening, eight months old, born in Erbesbudesheim and living in Erbesbudesheim. Son of Baer Salomon and Roes nee Benjamin. On the declaration made by Baer Salomon, his father, resident of Erbesbudesheim and a merchant, and Francois Colin, resident of Erbesbudeshem, a barber and a neighbor.

A year later, Taubechen (who became Eva) was born:

Birth record of Taubchen Baer/Eva Schoenfeld 1806

Act of birth: In the year 1806 on the 2d of June in the afternoon appeared before the mayor of Erbesbudesheim… Baehr Salomon, a merchant, 34 years old, living in Erbesbudesheim, No. 66, and presented to us a female child of him and his legal wife Rosine nee Benjamin born the 2d of June at 5 in the morning and also stated that he wanted to give the child the name Taubchen. [Witnesses and signatures.]

The children born after 1808 were given the name Schoenfeld, including my 3-x great-grandmother, Babetta. You will see that on this record, Bernard and Rosine are referred to with surnames.

Babete Schoenfeld birth record 1806

In the year 1810, the 28th of February, at nine in the morning, Bernard Schoenfeld, 37 years old, a merchant, and a resident of Erbesbudesheim,appeared before Andre Cronenberger, Mayor of Erbesbudesheim and presented a female child born the 28th of February in the morning of himself and Rosine nee Goldmann, his wife, and also declared that he wanted to give the child the name of Babet. [Witnesses and signatures]

In addition, I received records for other children of Bernard and Rosina Schoenfeld, ancestors I’d not known about before. The first two are in French, but the last two are in German because they occurred when the region was back under German control. The two in French follow the format and content of those above and evidence the births of a daughter Marianne, born June 29, 1812, and a daughter Rebecque, born July 20, 1814.

Birth record of Marianna Schoenfled 1812

Birth record of Rebecque Schoenfeld 1814

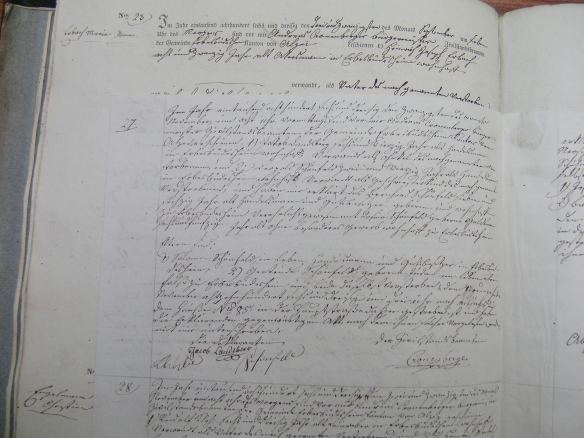

The last two are in German. Thank you to Matthias Steinke for the translations. The first record is for the birth of another daughter, Zibora, in 1818.

Birtn record of Zibora Schoenfeld 1818

In the year 1818, the 23rd of May came to me, the mayor and official for the civil registration of the comunity of Erbesbuedesheim, county of Alzey, Bernhard Schoenfeld, 45 years old, merchant, residing in Erbesbuedesheim, who reported, that at the 22nd of May at 11 o´clock in the night a child of female sex, which he showed me, was born and whom he intends to give the first name Zibora, and which he declared to have fathered with his wife Rosina Goldmann, 35 old, residing in Erbesbuedesheim. The child was born in the Hauptstr. nr. 77. This declaration and presentation happened in presence of the witnesses Johannes Knobloch, 55 years old, farmer, in Erbesbuedesheim residing and Jacob Landesberg, 29 years old, farmer, in Erbesbuedesheim residing, and have the father and the witnesses signed his birth-record and it was read to them. Signatures

The last child of Bernard and Rosine for whom I have a record was their daughter Saara, born in 1820:

Birth Record of Saara Schoenfeld 1820

In the year 1820 the fifteenth of October at twelve o´clock midday came to me, mayor and official for the civil registration of the comunity Erbes-Buedesheim Bernhard Schoenfeld, 51 years old, merchant, residing in Erbes-Buedesheim, who reported, that at the fifteenth October at two o´clock in the morning a child of female sex, whom he showed me, was born and whom he intends to give the name Saara, and he also reported, that he fathered the child with Rosina Goldmann, 41 years old, residing in Erbes-Buedesheim, his legal wife. This declaration and showing happened in presence of the witness Johannes Knobloch, 57 years old, farmer, and Jakob Landsberg, 28 years old, merchant, both residing in Erbes-Buedesheim, and have the father and the witnesses with me this present birth-certificate after it was read to them, signed. Signatures

In the midst of all these births, there was also a death. On February 16, 1813, Salomon Schoenfeld, father of Bernard Schoenfeld, died at age 63 (or is that soixant treize meaning 73?). His occupation was given as “cultivateur,” or cultivator, which I assume means that he was a farmer. The witnesses to his death included Benoit Schoenfeld, his son, age 23, a “propietaire” or owner, but no indication of what he owned. This must have been a younger brother of Bernard since in 1813 Bernard would have been at least 40 years old. (His age seems to vary from birth record to birth record.)

Death Record of Salomon Schoenfeld 1813

There is also a record for the birth of the child of an Isaac Schoenfeld and a Barbe Goldmann who is probably also a family member, though I am not sure what the exact connection was between these Goldmanns and Schoenfelds and Bernhard and Rosina, my 4x great-grandparents. But the number of marriages between a Schoenfeld man and a Goldmann woman are somewhat revealing. Here is a third such marriage, this one between Rebeka (Rebecque) Schoenfeld, the daughter of Bernhard and Rosina, and Salomon Goldmann. Is it any surprise that Ashkenazi Jews come up with thousands of matches when DNA testing is done? We are all interrelated at so many different levels.

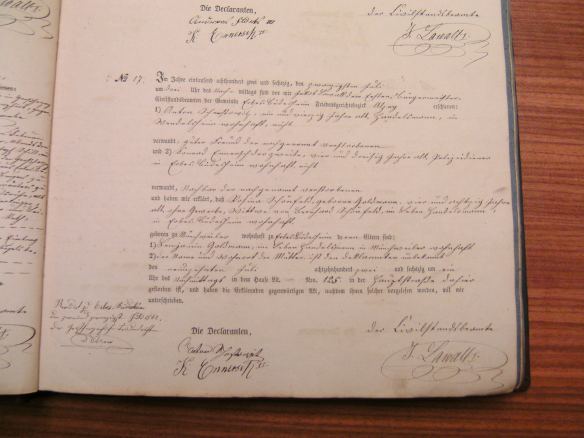

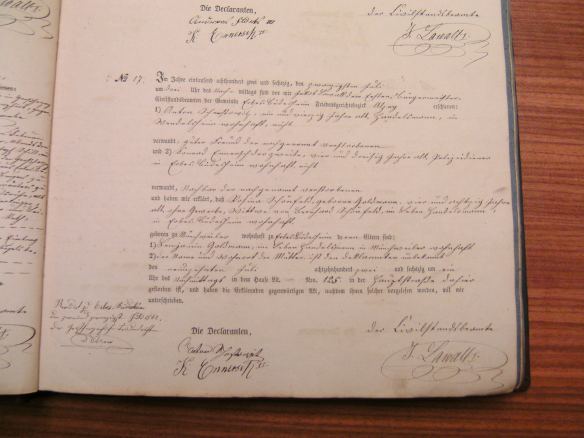

Marriage Record for Rebecque/Rebkah Schoenfeld and Salomon Goldmann

In the year 1834 on the fifteenth October at ten o´clock pre midday came to me, Andreas Cronenberger mayor and official for the civil registration of the comunity Erbes-Buedesheim, county of Alzey:

Salomon Goldmann, 42 years old, merchant, residing in Kirchheimbolanden, Rhein-county, Bavaria, born in …thal, like it was presented to me by a certificate of the district-court Kirchheimbolanden from the 24th of December 1807, which was certified by the district-court in Mainz, the adult son of 1. Joseph Goldmann, 75 years old, during his lifetime a merchant in Kirchheimbolanden, deceased there the 8th of November, 1800 (some parts here were cut off) 2. Friederike Goldmann, widow, nee Goldmann, 62 years old, without profession residing in Kirchheimbolanden and here present and giving her confirmation and who declared to be unable to write.

And on the other hand, Rebeka Schoenfeld (Schönfeld), 20 years old, born in Erbebudesheim in 1814, like I have seen in the present birth-register of the year 1814, without profession, in Erbes-Buedsheim residing.

Minor daughter of 1. Bernhard Schoenfeld, 62 years old, merchant and owner of a manor, in Erbes-Buedesheim residing. 2. Rosina Schoenfeld nee Goldmann, 55 years old, without profession, in Erbes-Buedesheim residing, both are present and giving their confirmation.

The appearing people asked me to do the marriage. The proclamation was published at the main-door of the comunity-building the September 24, 1834 at noon and the second the September 26 at noon in Erbes-Buedesheim and in Kirchheimbolanden the 14th of September the first time and the 21st of September of the same year the second time was made.

Due to the case, that no objections against this marriage appeared, and after reading the sixth chapter of the civil-rights-lawbook which is titled „about the marriage“ I asked them whether they want to marry each other. Both confirmed this question and I declared that Salomon Goldmann, widower from Kirchheimbolanden and the maiden Rebeka Schoenfeld of Erbes-Buedesheim are from now on connected by the matrimony.

About this act this certificate was made in presence of the following witnesses:

Georg Peter Erbach, 54 years old, member of the regional council and manor-owner in Erbes-Buedesheim, a neighbour of the bride, not related. Johannes Klippel, 45 years old, farmer in Erbes-Buedesheim, not related, a neighbour of the bride, Christoph Zopf, 49 years old, farmer in Erbes-Buedesheim, not related, a neighbour of the bride, Johannes Härter, 82 years old, comunity-servant in Erbes-Buedesheim, not related, a neighbour of the bride. After happened reading have all parts this document with me signed. Signatures

I have a couple of observations about this marriage certificate. First, the groom was a widower and 24 years older than the bride. Also, Rebeka was younger than her sister Babete or Babetta, my 3x-great-grandmother, yet married before her, even though this would appear to have been an arranged marriage. Did Babetta object to marrying Salomon? Or did Salomon choose Rebeka over her older sister?

Also, I was struck by the fact that Bernard was described not just as a merchant, as he had been in the records of his children’s births, but as the owner of a manor. Perhaps this explains why my Schoenfeld relatives were living in this small village with almost no Jewish residents. Bernard must have been quite successful to be a manor owner.

Two years after this wedding, Bernard Schoenfeld died.

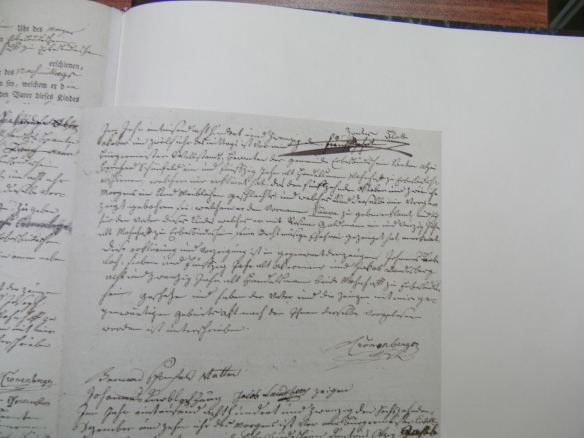

Death record of Bernard Schoenfeld 1836

In the year 1836 November 20th, at eight o´clock pre midday came to me, Andreas Cronenberger, mayor and official for the civil registration of the comunity Erbes-Buedesheim, county of Alzey, 1. the Jakob Landsberg, 46 years old, merchant in Erbes-Buedesheim residing, related as uncle of the below named deceased, and 2. Leopold Schoenfeld, 42 years old, merchant, in Erbes-Buedesheim residing, related as sibling of the below named deceased, and have reported to me that Bernhard Schoenfeld, 67 years old, merchant and manor-owner, born and residing in Erbes-Bueresheim, married to Rosina Schoenfeld, nee Goldmann ,56 years old, without profession, residing in Erbes-Buedesheim. Parents were: Salomon Schoenfeld, during lifetime merchant and manor-owner in Erbes-Buedesheim, 2. Gertrude Schoenfeld nee Judah, during lifetime also residing in Erbes-Buedesheim.

Died November 1836 at three o´clock past midday in house nr 85 in the Hauptstrasse (Mainstreet) here is deceased and have the here present this certificate after it was read to them with me undersigned.

In this record, Bernard’s father Salomon is described as a merchant and manor owner, not a cultivator. I am not sure how to reconcile that with the earlier record of Salomon’s death. The above record also reveals two more relatives: Leopold Schoenfeld, another brother of Bernard, and Jakob Landsberg, an uncle. But Jakob Landsberg was over 20 years younger than Bernard. Perhaps he was a nephew? Leopold Schoenfeld’s headstone appeared in the video I posted in the last post. Here’s a screenshot from that video:

Leopold Schoenfeld headstone

Just a few months after Bernard Schoenfeld died, his daughter Babete, my 3-x great-grandmother, married Moritz Seligmann on February 14, 1837.

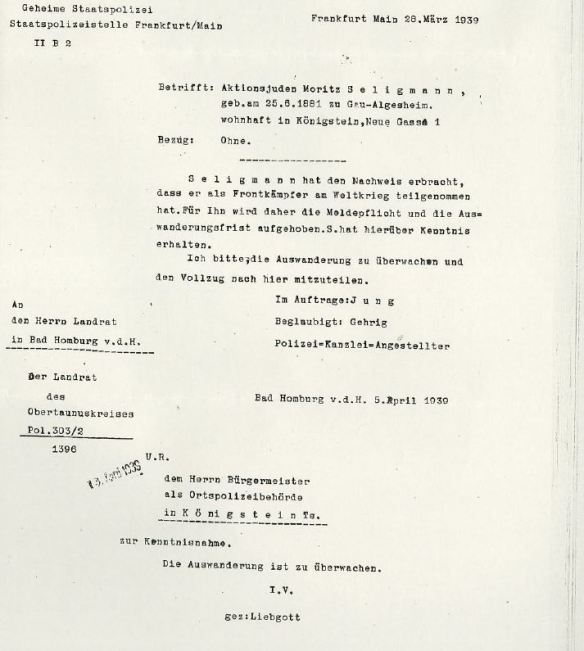

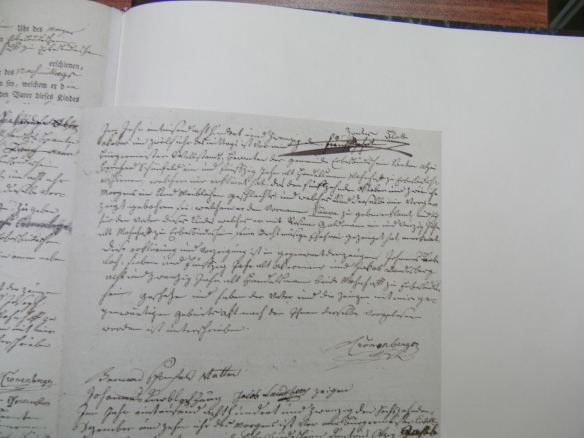

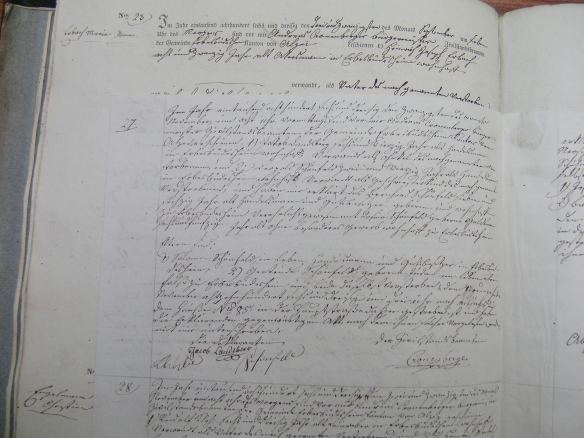

Marriage record of Babete Schoenfeld and Moritz Seligmann 1837

In the year 1837 the 14th of the month February, at three o´clock past midday to me, Peter Cronenberger, mayor and official for the civil registration of the comunity Erbes-Buedesheim, county of Alzey came:

Moritz Seligmann, 38 years old, widower of Eva Seligmann, nee Schoenfeld, deceased in Gaulsheim the 12th of May 1835 as it is written in the death-register of the comunity Gaulsheim of the year 1835, merchant, in Gau Algesheim residing, like it is in the birth-records of the community Gau Algesheim to find, adult son of 1. Jacob Seligmann, 63 years old, merchant, in Gaulsheim residing, 2. Martha Seligmann nee Mayer, 63 years old, in Gaulsheim residing, both not present, but giving their permission to this marriage according a notary-certificate of the notary Wieger in Gaulsheim from the 6th of February, 1837,

and on the other hand, Babete Schoenfeld, 26 years old, without profession, in Erbes-Buedesheim residing, born the February 28, 1810, like it is stated in the birth-register of the comunity Erbes-Buedesheim of the year 1810, adult daughter of 1. Bernhard Schoenfeld, during lifetime merchant, in Erbes-Buedesheim residing, deceased 19th of November 1836, as it is stated in the death-register of the comunity Erbes-Buedesheim, 2. Rosina Schoenfeld, nee Goldmann , 56 years old, in Erbes-Buedesheim residing, last named here present and consenting to the marriage. ….

Due to the case, that no objections against this marriage appeared, and after reading the sixth chapter of the civil-rights-lawbook which is titled ‘about the marriage,“ I asked them whether they want to marry each other. Both confirmed this question and I declared that Moritz Seligmann, merchant in Gau Algesheim residing and Babete Schoenfeld, without profession in Erbes-Buedesheim residing, are from now on legally connected by the matrimony.

About this act I made this certificate in the presence of the following witnesses: [Witnesses and signatures]

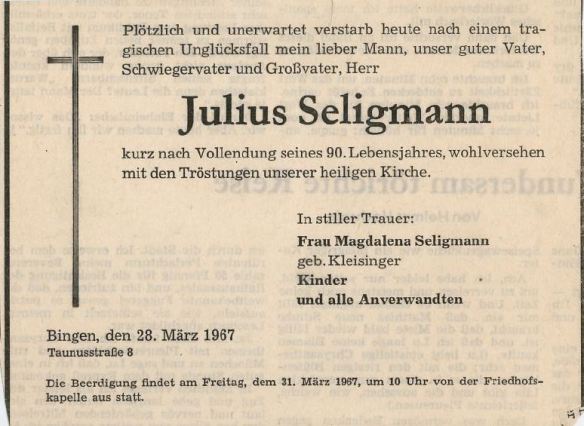

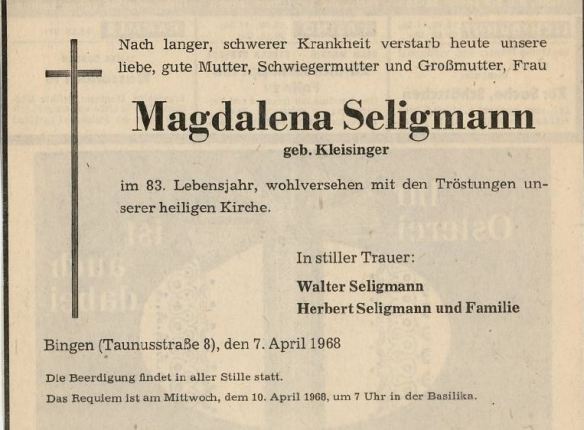

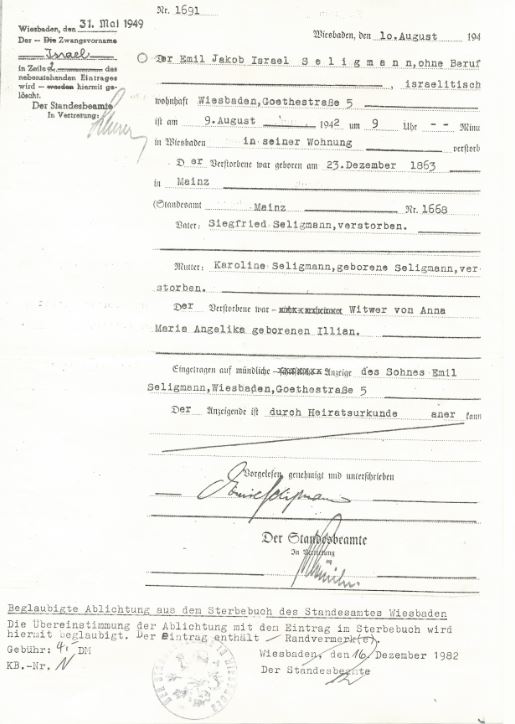

This marriage record answered a question that I had had about the two sisters both marrying Moritz Seligmann. According to this record, Eva Schoenfeld had died on May 12, 1835. Eva died in the aftermath of giving birth to her fourth child, Benjamin, who was born on May 10, 1835.

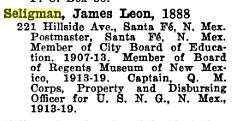

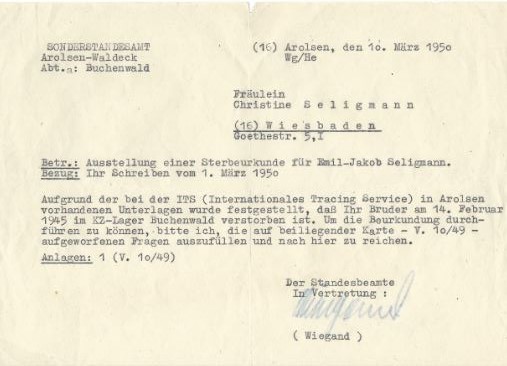

Her sister Babetta (as it was later spelled) became the instant mother of Eva’s four children, who then ranged in age from Benjamin, not yet two years old, to eight year old Sigmund, who would be the first to come to the US and settle in Santa Fe. Babetta not only had these four children to care for; she must also have become pregnant almost immediately after the wedding because my great-great-grandfather Bernard Seligman, obviously named for Babetta’s father Bernard Schoenfeld who had died the year before, was born on November 23, 1837, just nine months and nine days after the marriage.

The last record I received from Erbes-Budesheim was the death record for Rosina Goldmann Schoenfeld, dated July 19, 1862. She was 84 years old. She was my 4-x great-grandmother. All I know about her is where she was born, her father’s name, her husband’s name, and the names of her children and some of her grandchildren. I know that she lost one child at eight months old, an adult daughter in the aftermath of childbirth, and her husband almost thirty years before she died. It’s not a lot, but it is remarkable to me that I know even that much about a woman who was born in the 18th century in Germany.

Death record of Rosina Goldmann Schoenfeld 1862

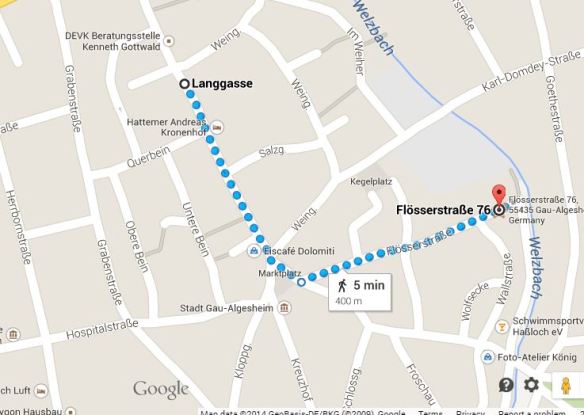

So what have I learned about my Schoenfeld ancestors and their lives in Erbes-Budesheim from all these documents? First, they must have been one of only a very few Jewish families in Erbes-Budesheim if the total Jewish population was just 23 people. Second, they must have been fairly comfortable living in that small town, living as merchants and manor owners. But there was no future for their family in the town. Bernard Schoenfeld and Rosina Goldmann had only daughters who survived to adulthood. To find marriage partners for their daughters, Bernard and Rosina had to look outside of Erbes-Budesheim. Their 20 year old daughter Rebeka Schoenfeld married a 44 year old widower from a town in Bavaria, about ten miles from Erbes-Budesheim. Their daughter Eva married Moritz Seligmann and moved to Gau-Algesheim. Then their daughter Babetta, my 3-x great-grandmother, married Moritz after her sister died. These young women must have had no choice but to marry and move away from Erbes-Budesheim. No wonder the town’s Jewish population never grew and eventually declined and disappeared.

But the cemetery still exists, and Erbes-Budesheim is one more town to add to my list of ancestral towns I’d like to visit one day.

[1] Gerd Braun did not use the Hebrew terms “ben” or “bat” for son or daughter of, but simply referred to them as, for example, Baehr Salomon. I am assuming, however, based on Jewish practice, that the second name would have been the father’s first name. Thus, Baehr Salomon is really Baehr son of (ben) Salomon.

[2] According to Wikipedia, Frimaire “was the third month in the French Republican Calendar. The month was named after the French word frimas, which means frost. Frimaire was the third month of the autumn quarter (mois d’automne). It started between November 21 and November 23. It ended between December 20 and December 22. It follows the Brumaire and precedes the Nivôse.” Benedict was thus born about December 6.

[3] Messidor in the French Republic Calendar was equivalent to June 19 to July 18. The 17th would be equivalent to July 6.