Today is my grandmother Gussie Brotman Goldschlager’s birthday; she was born on this day in 1895. And so it is very appropriate that on this day, which also is the third anniversary of this blog, I return to my Brotman family story. This is the story of the mystery cousins I discovered last fall—the Goldfarbs.

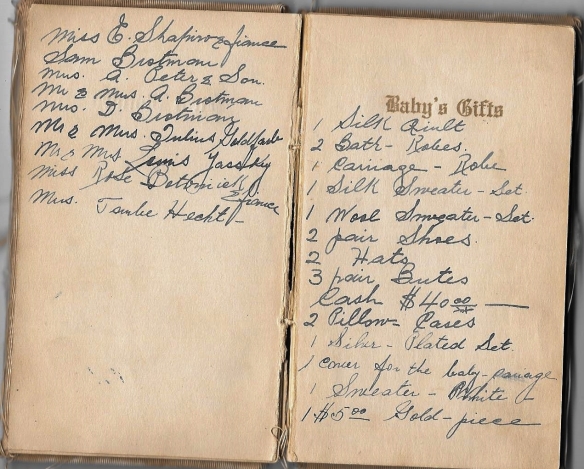

Back on December 7, 2015, I wrote about my aunt’s baby book from 1917, and I mentioned that on the list of those who came to see my aunt as a newborn were a couple named Mr. and Mrs. Julius Goldfarb. When I asked my mother if she knew who they were, she vaguely recalled that they were somehow cousins of my grandmother, but she wasn’t sure whether the actual cousin was Julius or his wife, whose name she thought might have been Ida.

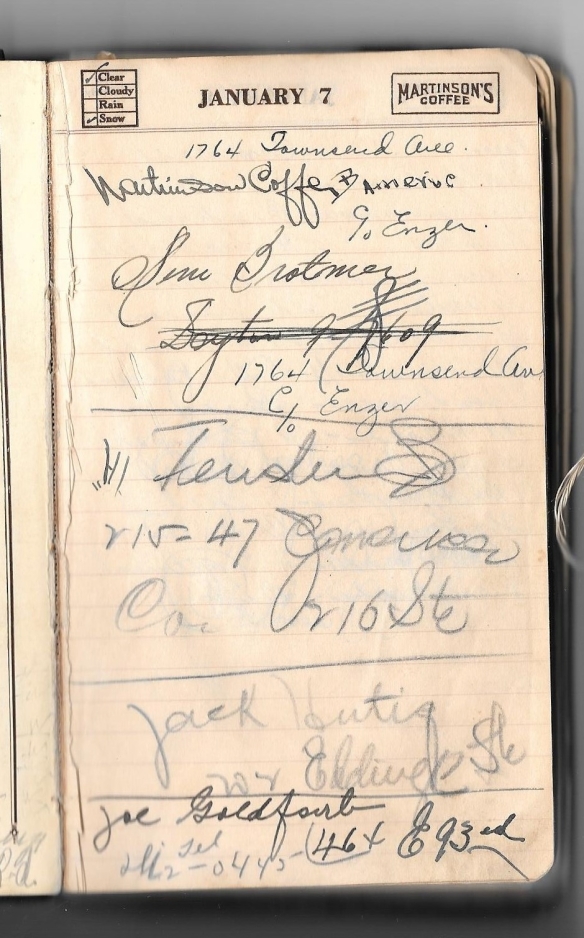

I also wrote back in December about my grandfather’s pocket calendar and notebook and all the wonderful information and insights I found there. Among those bits of information were addresses for two other people named Goldfarb: S. Goldfarb, who lived at 577 Williams Avenue, and two entries for Joe Goldfarb, one at 464 East 93rd Street and one at 191 Amboy Street. I assumed these were relatives connected to Julius, but had no idea how.

With those limited hints, I started researching, and I found quite a bit. In fact, I connected with two of the descendants of Julius and Ida Goldfarb, and I fully intended to write about the Goldfarbs sooner, but somehow the Schoenthals took over my blog, and poor cousin Julius was shelved for over ten months. Now it’s time to return to this story and reveal what I learned from these tidbits of information.

First, I searched for Julius and Ida Goldfarb because I had two names to work with and because Julius Goldfarb seemed like it would be less common than Joe Goldfarb. I easily found Julius and Ida and their children on the 1940, 1930, and 1920 census reports; all three reports had them living in Jersey City, New Jersey. In 1920, Julius was working in a liquor business; in 1930 he was the proprietor of a real estate business, but in 1940 he was again in the liquor business, now working on his own account.

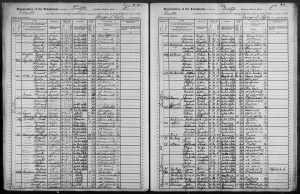

Julius Goldfarb and family 1920 US census

lines 70-73

Year: 1920; Census Place: Jersey City Ward 3, Hudson, New Jersey; Roll: T625_1043; Page: 17B; Enumeration District: 135; Image: 1104

The 1920 census said that Julius was born in Austria and was 33 (so born in about 1887); the 1930 census reports his age as 42 and birthplace as Poland.

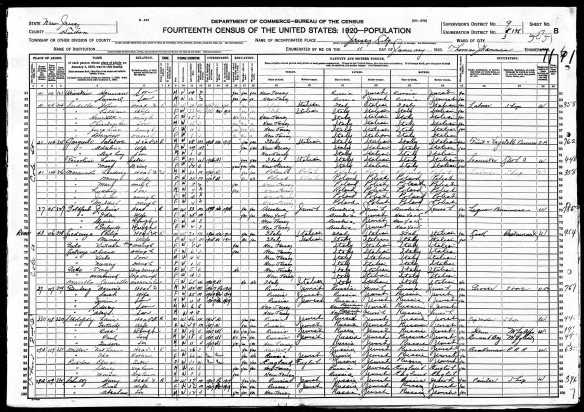

Julius Goldfarb and family 1930 US census, lines 40-45

Year: 1930; Census Place: Jersey City, Hudson, New Jersey; Roll: 1352; Page: 29A; Enumeration District: 0075; Image: 209.0; FHL microfilm: 2341087

On the 1940 census he is 52 and reports his birthplace as Austria. Julius and Ida had four daughters: Sylvia (1915), Gertrude (1917), Ethel (1923), and Evelyn (1925).

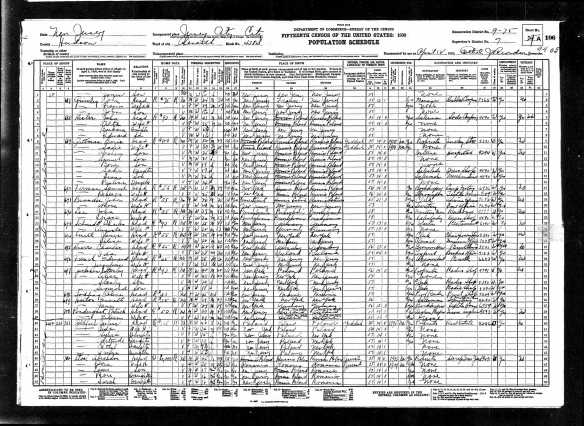

Julius Goldfarb and family 1940 census lines 13-17

Year: 1940; Census Place: Jersey City, Hudson, New Jersey; Roll: T627_2406; Page: 7A; Enumeration District: 24-197

All of this was very interesting, but it didn’t help me figure out if this was the right Julius Goldfarb or how he was related to my grandmother. Or was it Ida who was the relative? So I continued searching.

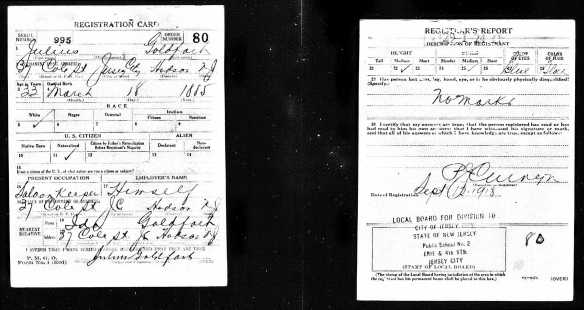

Julius’ World War I draft registration contained no new information, except the fact that his liquor business in 1917 was a saloon and that he and his family lived at the same address as the saloon: 27 Cole Street. The draft registration also provided me with a more precise birthdate for Julius, March 18, 1885.

Julius Goldfarb World War I draft registration

Registration State: New Jersey; Registration County: Hudson; Roll: 1712213; Draft Board: 10

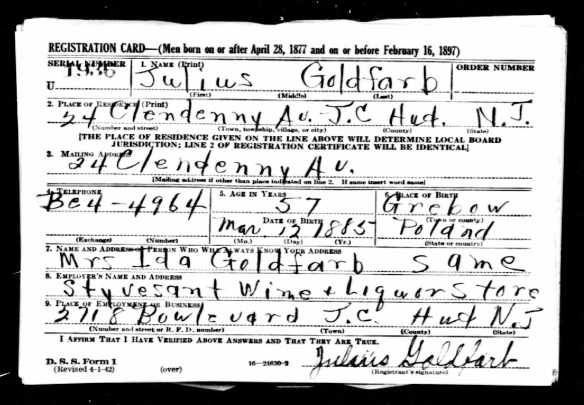

Then things started to get more interesting. I located the World War II draft registration for Julius, and although it had a different birthday, March 12, 1885, instead of March 18, I knew this was the right person, given that the address was the same as the address on the 1940 census for Julius as was the occupation (liquor store) and his wife’s name (Ida). But the big revelation here was Julius’ birthplace—Grebow, Poland, the same place that my great-uncles Abraham and David Brotman had listed as their residence on the ship manifest when then immigrated to the US. My heart skipped a beat. It definitely looked more and more possible that Julius was a cousin.

Julius Goldfarb World War II draft registration

The National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; Draft Registration Cards for Fourth Registration for New Jersey, 04/27/1942 – 04/27/1942; NAI Number: 2555983; Record Group Title: Records of the Selective Service System; Record Group Number: 147

So I searched then for a marriage record for Julius and Ida, and on FamilySearch I found the index listing for it, and now I was truly excited. According to the index on FamilySearch, Julius Goldfarb’s mother was named Sarah Brothman. I’d seen my great-grandfather’s name spelled that way instead of Brotman (and sometimes Brodman), and it seemed more and more likely that Julius Goldfarb was my relative, probably through my great-grandfather’s side of the family.

The index listing also included Ida’s birth name—Hecht. I recalled from my aunt’s baby book that there was a visitor named Mrs. Taube Hecht (see the last name listed on the image above). Now I knew that that was Ida’s mother.

But more importantly, I now knew the names of Julius Goldfarb’s parents, Sam and Sarah, and that enabled me to search for them and find additional records.

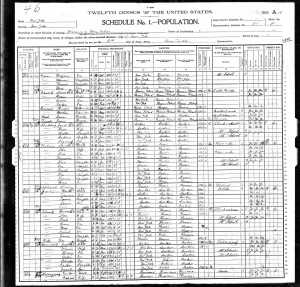

On the 1910 census, Sam and Sarah Goldfarb were living on Avenue C in New York City with six children, including Julius, who was then 25. The others were Morris (23), Bessie (18), Joseph (12), Leo (11), and Rosie (9). Joe and Leo were born in New Jersey and Rosie in New York, but the rest of the family were listed as born in Austria. Sam was working as a tailor in a coat factory, Julius as a conductor for a car company (I assume a streetcar company), and Morris as a cutter in a neckwear factory.

From this census record, I now knew that Joe Goldfarb, who was listed twice in my grandfather’s list of addresses, was a brother of Julius and that he was born in about 1898. The 1910 census also revealed when Sam and Sarah had immigrated. Sam had arrived in 1892, Sarah and the European born children in 1896.

Sam Goldfarb and family 1910 US census, lines 8-17

Year: 1910; Census Place: Manhattan Ward 11, New York, New York; Roll: T624_1012; Page: 17A; Enumeration District: 0259; FHL microfilm: 1375025

Knowing the names of the other children of Sam and Sarah Goldfarb helped me locate them on other census records. The 1915 New York census record proved quite revealing. Sam and Sarah were still living at 131 Avenue C in New York City with Morris, Bessie, Joseph, Leo, and Rose (Julius was now married), and Sam was still working as a tailor, as was Morris. When I looked down the page from where Rose Goldfarb is listed at the top of the right hand side of the page, I saw a very familiar name—Hyman Brotman, my grandmother’s brother Hymie. Hyman and his wife Sophie (spelled Soffie here) and their three sons were living at the same address, in the same building, as the Goldfarbs.

Sam Goldfarb and family 1915 NY census

New York State Archives; Albany, New York; State Population Census Schedules, 1915; Election District: 18; Assembly District: 06; City: New York; County: New York; Page: 84

And then right below the Brotman family was the Hecht family—Jacob and Tillie Hecht and their children. I assume these were the parents of Ida Hecht Goldfarb, Sam Goldfarb’s wife. (Tillie is often an alternative name for Taube.) They also were living at 131 Avenue C in the same building as Hyman Brotman and his family and Sarah and Sam Goldfarb. The coincidences were clearly not just coincidences.

And it only got better. I found Sam and Sarah Goldfarb on the 1905 New York census, living with seven children—Julius, Morris, Bessie, Joseph, Leo, and Rose, plus another daughter, Gussie, who was seventeen, two years younger than Morris and two years older than Bessie.

Sam Goldfarb and family 1905 NY census

New York State Archives; Albany, New York; State Population Census Schedules, 1905; Election District: A.D. 12 E.D. 06; City: Manhattan; County: New York; Page: 32

I assumed that this newly discovered daughter named Gussie had married between the 1905 NY census and the 1910 US census since she was not living with the family in 1910, and my search revealed that she had married Max Katz on April 12, 1910. I found her marriage on FamilySearch indexed as Josi Gossi Goldfarb, daughter of Sam Goldfarb and “Sarah Brohmen.” Another piece of the puzzle tying Sarah Goldfarb to my great-grandfather.

But what was even more exciting about the 1905 New York census was what it revealed about where Sam and Sarah Goldfarb and their children were living: 85 Ridge Street in New York City. Why was that exciting? Because my great-grandmother Bessie Brod Brotman was living across the street at 84 Ridge Street in 1905 with my grandmother Gussie and her siblings, Tillie, Frieda, and Sam. There seemed to be no denying the fact that Sarah Goldfarb was somehow related to my grandmother’s family.

(My great-grandmother’s name is badly butchered here as Pearl Brauchman, but there’s no question that this is Bessie Brotman and her children, Tilly, Gussie, Frieda, and Sam; when Bessie married Philip Moskowitz, her second husband, in 1908, her address was 84 Ridge Street.)

I also now understood why Julius and Joe Goldfarb would have been listed in the baby book and the address list. In 1905 when she was ten years old, my grandmother was living right across the street from Julius and Joe Goldfarb and their siblings. Joe was just a year or two younger, and like my grandmother, he was the first American born child of his parents. Of course, Joe Goldfarb would be listed in the address book. Twice, in fact. Of course, Julius and Ida would have come to see my grandparents’ new baby in 1917.

There was still one prior census to find: the 1900 US census. The Goldfarbs were a little harder to find on this one because Sam was listed as Solomon here, and several of the other names don’t quite match. Although Sarah is listed as Sarah and Bessie as Bessie, there are two sons listed as Joseph; one, I assume, was Julius, given the approximate age. Morris was listed as Moses, Leo is Lewis, and Gussie as … Kate? Despite these discrepancies, I am quite certain that these are the right Goldfarbs. The immigration years are consistent with the 1910 census; Sam (Solomon) is a tailor. The parents and older children were born in Austria, and the ages are close if not precisely the same.

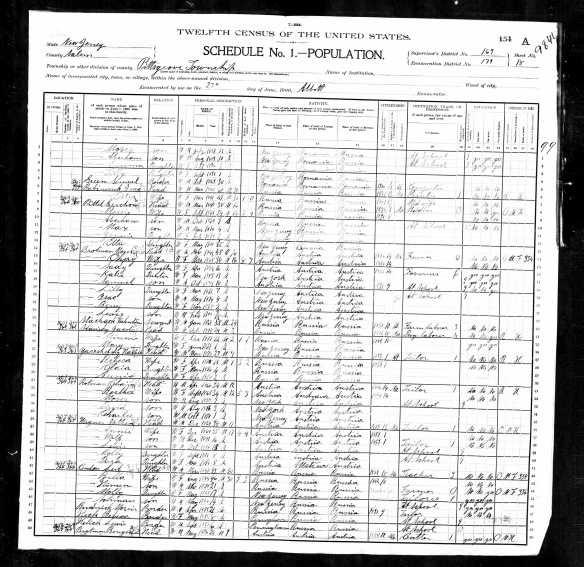

Sam Goldfarb and family 1900 US census

Year: 1900; Census Place: Pittsgrove, Salem, New Jersey; Roll: 993; Page: 17B; Enumeration District: 0179; FHL microfilm: 1240993

Again, what is particularly interesting here is where they were living: in Pittsgrove, New Jersey, where Moses Brotman and his extended family were living in 1900. In fact, Moses Brotman and his family are listed on the very next page of the census report in 1900. And Moses Brotman was the brother of my great-grandfather Joseph Brotman. One more piece of evidence that Sarah was a Brotman and related to me through my great-grandfather Joseph Brotman.

Moses Brotman 1900 census Year: 1900; Census Place: Pittsgrove, Salem, New Jersey; Roll: 993; Page: 18A; Enumeration District: 0179; FHL microfilm: 1240993

I had one more type of document to search for before moving forward and finding more recent records for the Goldfarb family, and those were ship manifests for the Goldfarbs. Although I’ve not yet been able to locate one for Sam Goldfarb, I did find one for Sarah and the children who were born in Europe, Julius, Morris, Gussie, and Bessie.

Sarah Goldfarb and children on ship manifest 1896

The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; Series Title: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; NAI Number: 4492386; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; Record Group Number: 85; Series: T840; Roll: 25

Once again the names don’t match exactly. Sarah is Surah, a Yiddish version of Sarah. Julius is Joel— Julius must have been the Americanized version of the Hebrew name Joel. Morris was Moische—again a Yiddish name they changed in America. Gussie was originally Gitel—as was the case with my grandmother Gussie. And Bessie was originally Pesie. The manifest indicates that they were all detained, and I need to find out more about that. It also says that they were going to Surah’s husband, Shlomo Goldfarb. Shlomo is a Yiddish version of Solomon. My guess is that Shlomo became “Sam” as the family Americanized their names. (I also think the enumerator in 1900 heard Gitel as “Kate.”)

And the icing on the cake is that the manifest lists their last residence as Grembow—or more likely, Grebow as Julius listed it on his draft registration almost fifty years later.

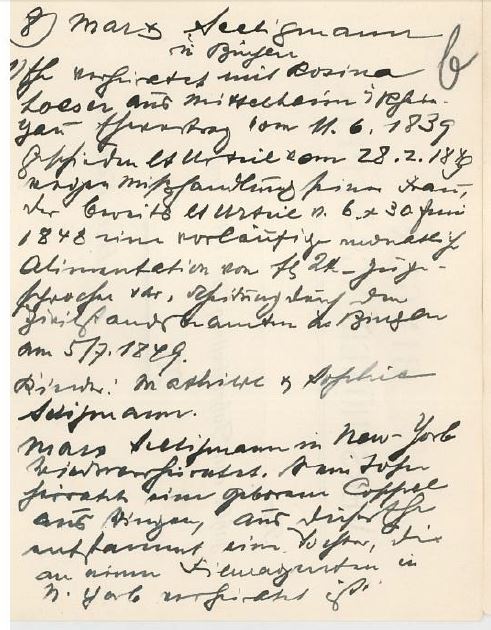

So these were my cousins. I was sure of it. But was Sarah Brothman/Brohmen Goldfarb my great-grandfather’s sister? How could I determine the answer to that question? I needed to order some actual records, search more deeply. More in my next post.