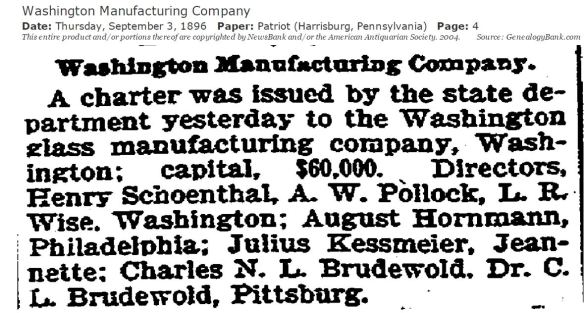

When I read my great-great-uncle Henry Schoenthal’s diary and learned that his little sister Malchen (later, Amalie, then Amelia, but I will call her Amalie throughout) was the first of his siblings to express an interest in following him from Germany to the US, I was intrigued. She was only twenty years old and not yet married. Who was this adventurous young woman?

Amalie Schoenthal arrived in Pennsylvania in September, 1867, and in 1870, she was living in Pittsburgh with her aunt Fanny Schoenthal Goldmith and her family and working as a domestic. In 1872, she married Elias Wolfe, the cattle drover, with whom she had six children between 1873 and 1885: Maurice, Florence (usually referred to as Flora), Lee (named for Amalie’s father Levi), Ira, Henrietta (or Etta, named for Amalie’s mother Henriette), and Herbert. Although Amalie’s life was likely very traditional for a married woman with six children, some of her children seemed to have inherited her adventurous spirit. Unlike most of the children and grandchildren of her older sister Hannah who stayed in Pittsburgh and the surrounding area for generations, most of the children of Amalie and Elias Wolfe ventured to places quite distant from Pittsburgh.

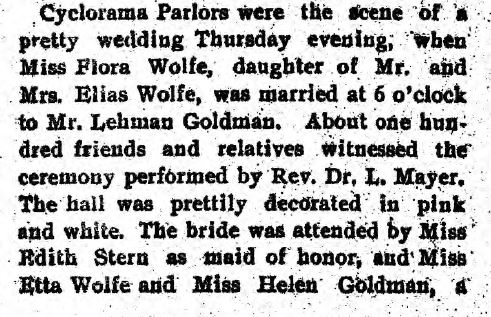

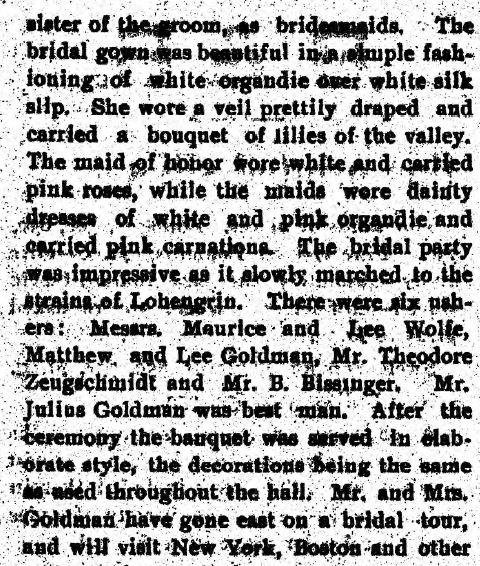

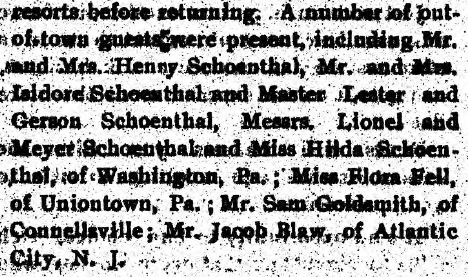

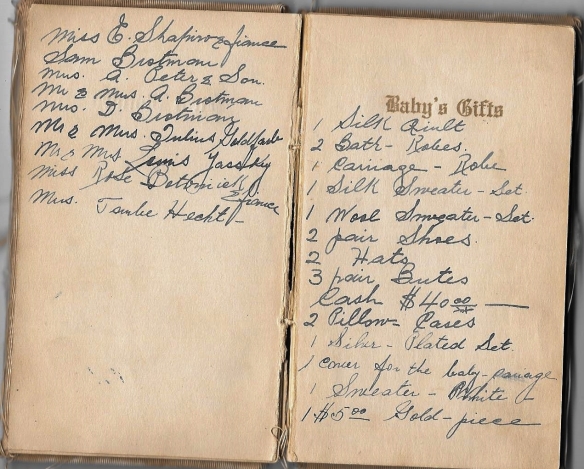

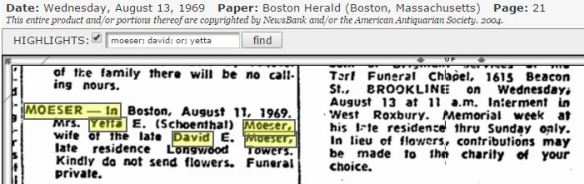

In 1899, Flora Wolfe, then 24 years old, was the first of the children of Amalie and Elias to marry. She married Lehman Goldman on June 1, 1899, as described here:

Jewish Criterion, June 2, 1899, pp.8-9

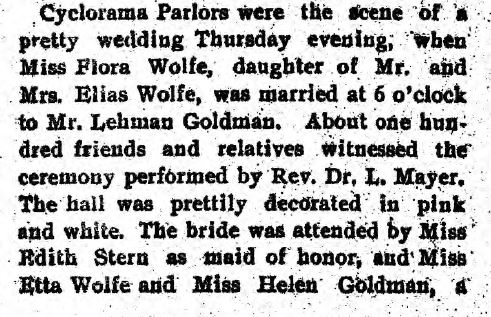

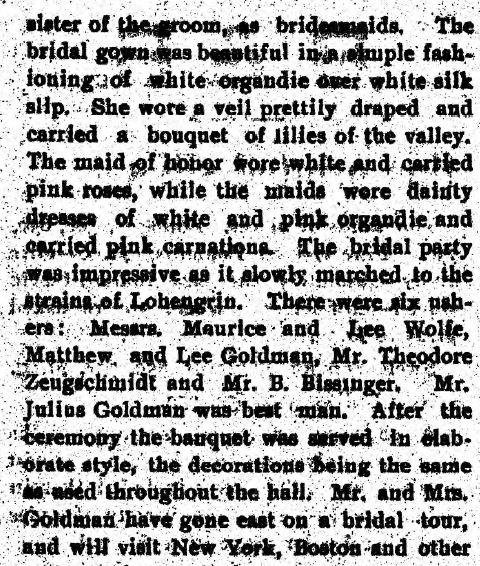

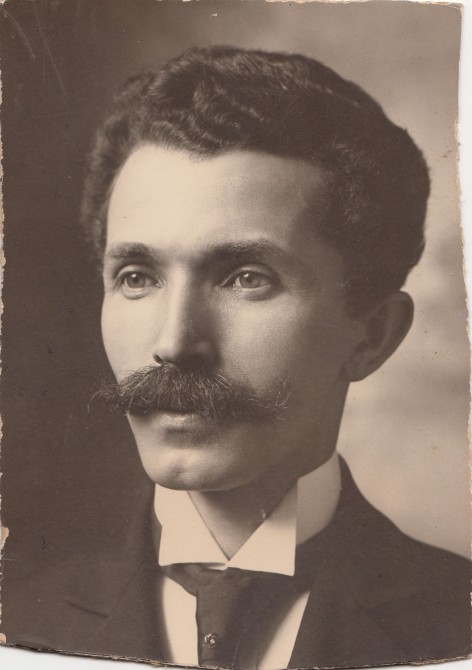

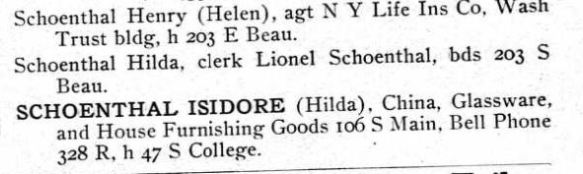

From the description of the wedding, it would seem that Elias Wolfe must have been doing quite well in his business as a cattle drover. A fancy wedding attended by over a hundred people would probably have been considered quite large in those times. Flora’s maid of honor was her first cousin, Edith Stern, daughter of Hannah Schoenthal Stern. Among the many guests, the last paragraph lists my great-grandparents, Isidore and Hilda (Katzenstein) Schoenthal, and their sons, my great-uncles Lester and Gerson, who would have been ten and seven years old at the time, respectively.

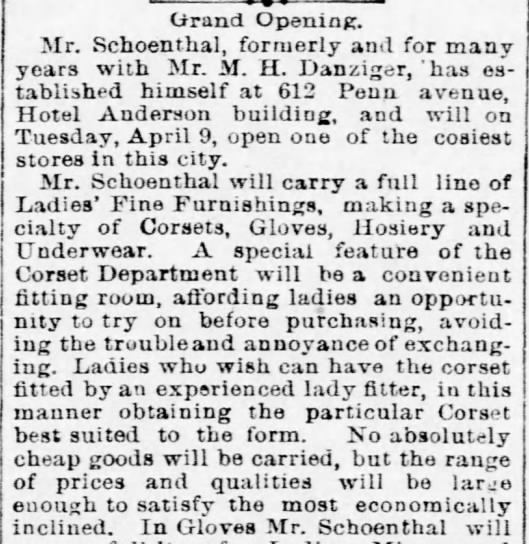

Flora’s groom, Lehman (sometimes spelled Leman) Goldman, was born in Baltimore in 1876, as was his father, Samuel Goldman, who was working as an insurance agent in 1900, according to the census. After marrying, Flora and Lehman were living with Lehman’s family in Pittsburgh, and Lehman was working as a traveling salesman in the “furnishing goods” business. I assume that that is another term for dry goods or clothing.

Flora and Lehman had four children in the first nine years of their marriage: Kenneth LeRoy (1901), Helen (1903), Donald (1905), and Marjorie (1907).

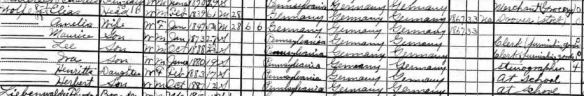

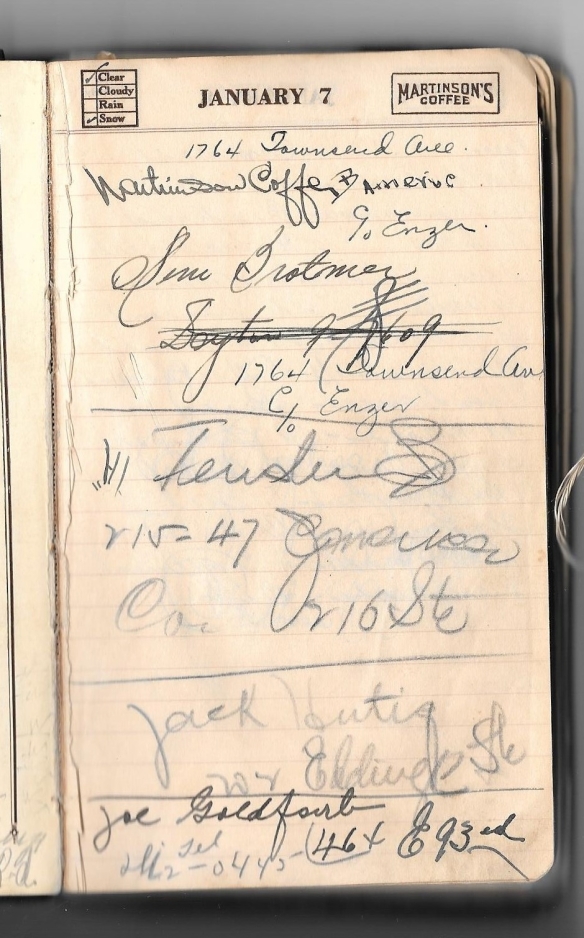

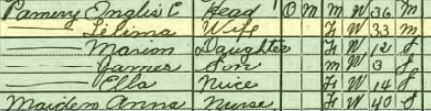

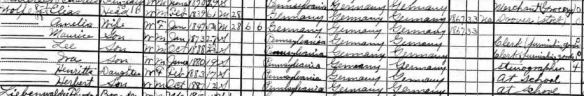

Flora’s sister and four brothers were still living at home with their parents Amalie (now called Amelia) and Elias Wolfe in 1900. Elias was still a drover. Maurice, now 27, and Lee, now 22, were clerks in a furnishings store. Ira was nineteen and working as a stenographer. The two youngest children, Henrietta, seventeen, and Herbert, twelve, were still in school.

Elias Wolfe and family, 1900 census

Year: 1900; Census Place: Allegheny Ward 2, Allegheny, Pennsylvania; Roll: 1355; Page: 14B; Enumeration District: 0018; FHL microfilm: 1241355

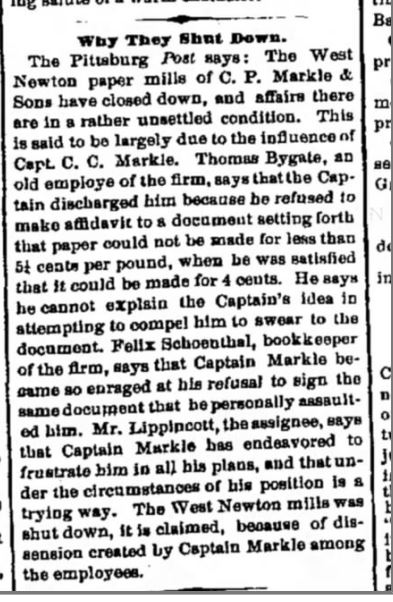

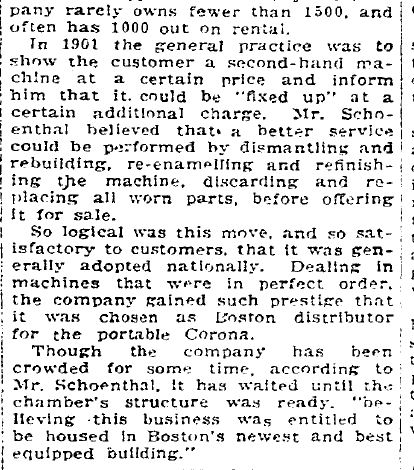

Lee must have married shortly after 1900 (although I cannot find any record or news story to confirm it) because he and his wife Wilhelmina (Minnie) Heisch had a son named Lloyd on February 25, 1902, and a daughter named Ruth in 1905. Minnie’s parents, John Heisch and Christine Kress, were born in Germany, and John was a carpenter. Although I found newspaper announcements of engagements and marriages for Minnie’s siblings, I did not find one for Minnie and Lee nor did I find any mention of the marriage in the Jewish Criterion. According to the entry in the 1908 Pittsburgh city directory, Lee was in the paper bag business.

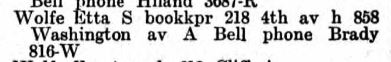

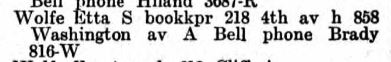

His brother Maurice, the oldest son, was living with his parents in 1908 and working as a salesman. Their sister Etta was working as a bookkeeper and also living at home.

![Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/wolfes-in-1908-pitt-directory.jpg?w=584)

Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

By 1910 and perhaps even earlier, Ira Wolfe had left Pennsylvania and moved to

San Francisco. He was 28 years old, working as a cashier for a lamp company, and lodging in someone’s home, according to the 1910 census. Herbert, the youngest child of Amalie and Elias Wolfe had also moved away by 1910; Herbert was 25 and had moved to Detroit where in 1910 he was working as a machinist and in 1911 as a sign writer. Thus, by 1910, the two youngest sons of Amalie and Elias had left for far off places. I can’t help but wonder what drove them to move away from the place where their extended family was living. Did they inherit their mother’s adventurous spirit? Or was it something else?

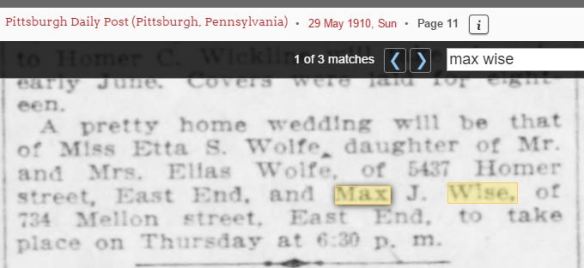

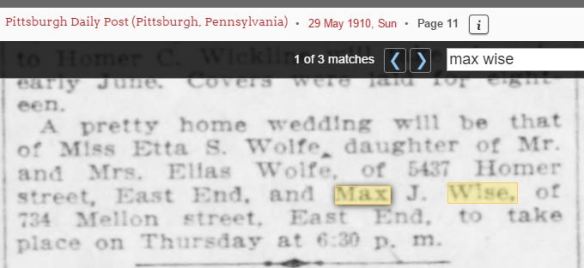

All the other Wolfes were still in Pittsburgh in 1910. Etta was living with her parents at the time of the census in April, but she married Maximillian Joseph Wise on June 2, 1910. Max was a German immigrant; although I cannot find him on the 1900 census, there was a Max Wise listed on the 1910 census who was living in Pittsburgh on Mellon Street, the same address given in the marriage announcement in the Pittsburgh Post Gazette.

Max Wise was a traveling salesman residing as a lodger in the residence of others at the time of the 1910 census.

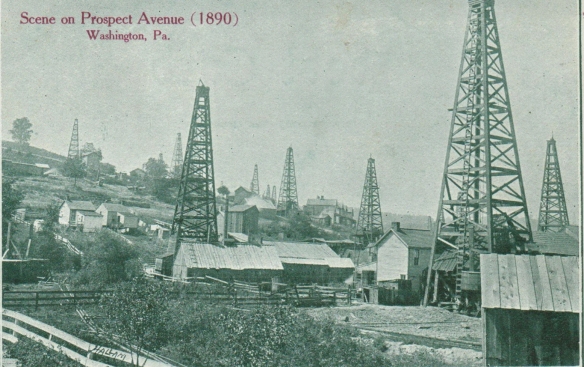

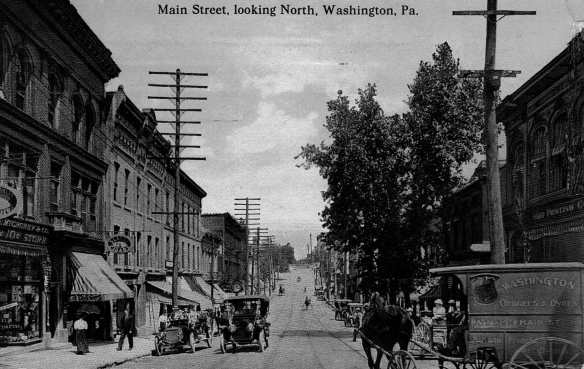

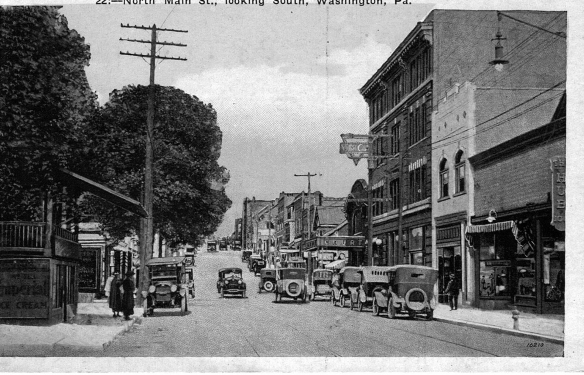

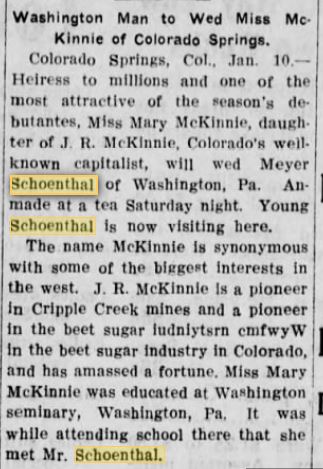

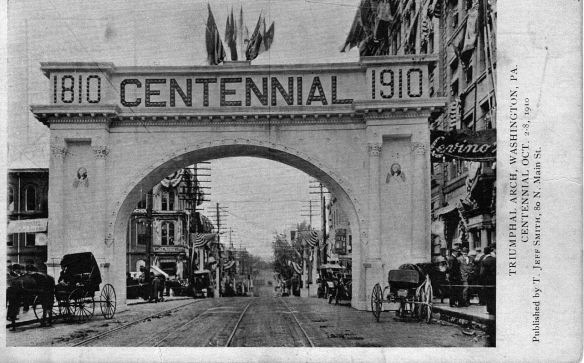

I cannot find Maurice Wolfe on the 1910 census, but he is listed as living in Canonsburg in both the 1909 and 1911 directories for Washington, Pennsylvania, selling men’s furnishings. His brother Lee was still living in Pittsburgh with his wife Minnie and their two children, Lloyd and Ruth; Lee was then a wrapping paper salesman.

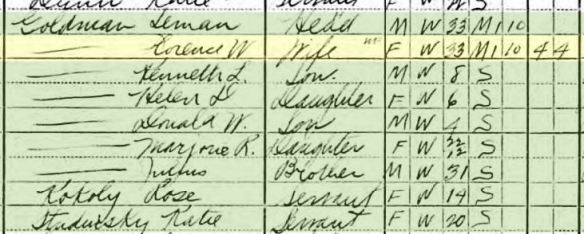

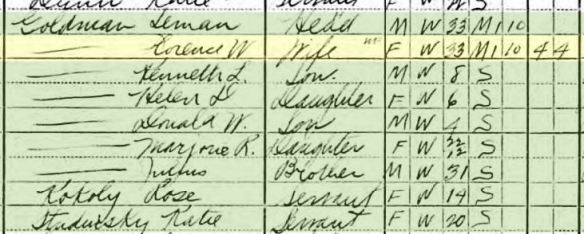

As for Flora (Florence, here), at the time of the 1910 census she and her husband Lehman Goldman were also still living in Pittsburgh where Lehman was a clothing merchant. Their four children were eight, six, four, and just about two years old when the census was taken on April 15, 1910.

Year: 1910; Census Place: Pittsburgh Ward 11, Allegheny, Pennsylvania; Roll: T624_1302; Page: 2A; Enumeration District: 0416; FHL microfilm: 1375315

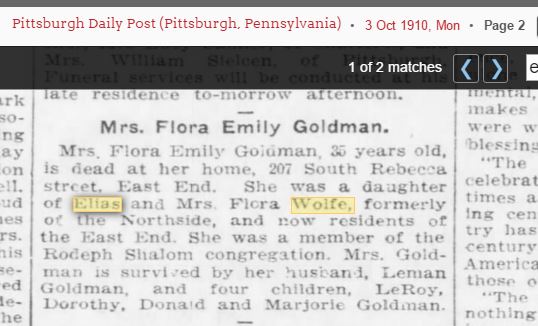

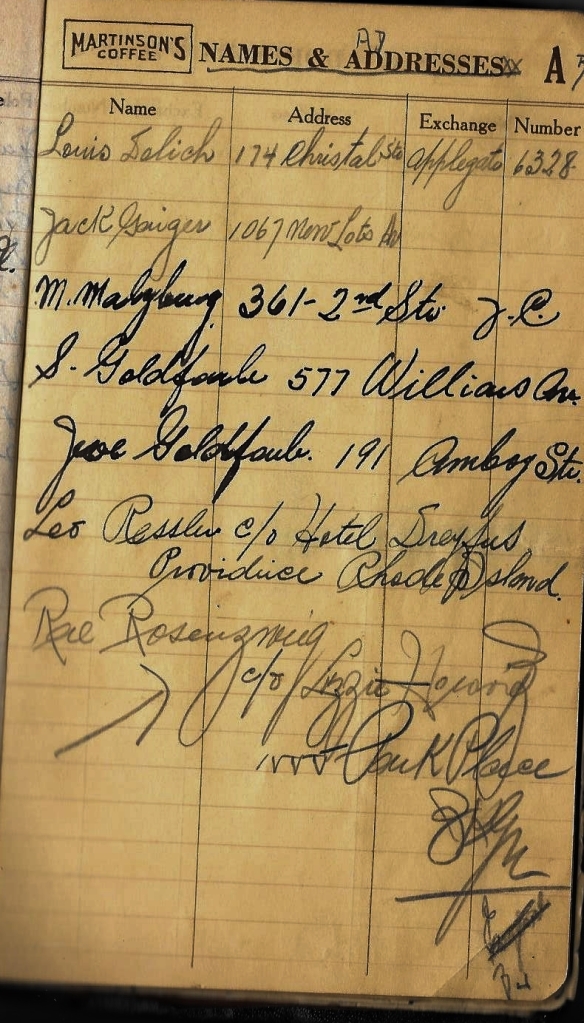

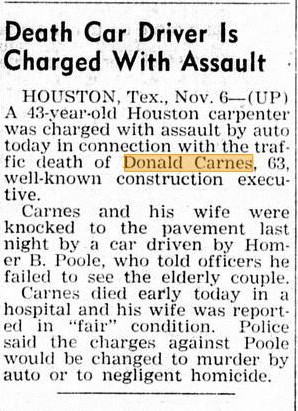

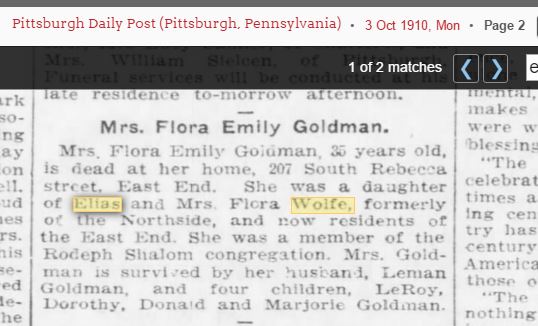

Just five months later the Wolfe/Goldman families suffered a terrible loss. Flora Wolfe Goldman, only 35 years old, died on September 30, 1910, from puerperal fever, also known as childbed fever.

![Flora Wolfe death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/flora-wolfe-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=533)

Flora Wolfe death certificate

Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Pittsburgh Daily Post, October 3, 1910, p. 2

According to Medicinenet.com, puerperal fever is:

Fever due to an infection after childbirth, usually of the placental site within the uterus. If the infection involves the bloodstream, it constitutes puerperal sepsis. Childbed fever was once a common cause of death for women of childbearing age, but it is now comparatively rare in the developed world due to improved sanitary practices in midwifery and obstetrics. Also known as childbirth fever and puerperal fever.

Since there is no record of another child born to Flora and Lehman, I assume that either the baby was stillborn or died shortly thereafter or that Flora had miscarried. Flora left behind her 34 year old husband and four very young children. Lehman remarried three years later on March 8, 1913; his second wife was Helene Hoffa, and they would have four more children together between 1914 and 1923.

Six months after Flora died, on March 3, 1911, Etta and Max Wise had their first child, a daughter whom they named Florence Emily, undoubtedly for Etta’s sister. A second child, a boy named Irving, was born the following year on October 12, 1912. In 1913, Etta and Max Wise relocated to Middletown, Ohio, where he opened a clothing store, as evidenced by the obituary written years later when Max Wise died, seen below.

I was curious about Middletown, Ohio and what drew Max and Etta to relocate there. Middletown is located roughly halfway between Cinncinati, Ohio, and Dayton, Ohio, and is about 280 miles west of Pittsburgh. According to the Middletown Historical Society website, the town, which started as an agricultural community, experienced tremendous growth in the 19th and early 20th century due to industrialization:

During the 1800’s and early 1900s Middletown became this bustling municipality due to the growth of industry. Many entrepreneurs developed their businesses and with the addition of ARMCO (now AK Steel) founded by George M. Verity, and Sorg Paper Company founded by Paul J. Sorg.

As reported on Wikipedia, the population of Middletown surged in these years, going from about 3,000 people in 1870 to over 9,000 by 1900 and to more than 23,000 by 1920. Max Wise must have seen it as a place of great opportunity; as they say on the old commercial for Barney’s clothing store in New York City, everyone needs clothes.

But were there Jews there? From the American Jewish Archives website, I found this information about the Jewish community in Middletown when Max and Etta Wise moved there:

In 1903, ten Orthodox Jewish families rented a small room on Clinton Street in which to hold services. Under the leadership of new Russian immigrant, Mr. Schomer, they rented a single Torah and created a makeshift Ark. As the Orthodox community grew, the rented shul on Clinton Street became too small for weekly Shabbat services, and in 1915, the community bought a structure on First Avenue, across from the public library. Rabbi Gilsey assumed the pulpit, and a regular religious school was formed. Three years later, in 1918, the shul was incorporated under the laws of the State of Ohio under the name “Anshe Sholom Yehudah Congregation.” By 1920 there were approximately thirty-five families in the congregation, all of whom spoke mainly Yiddish.

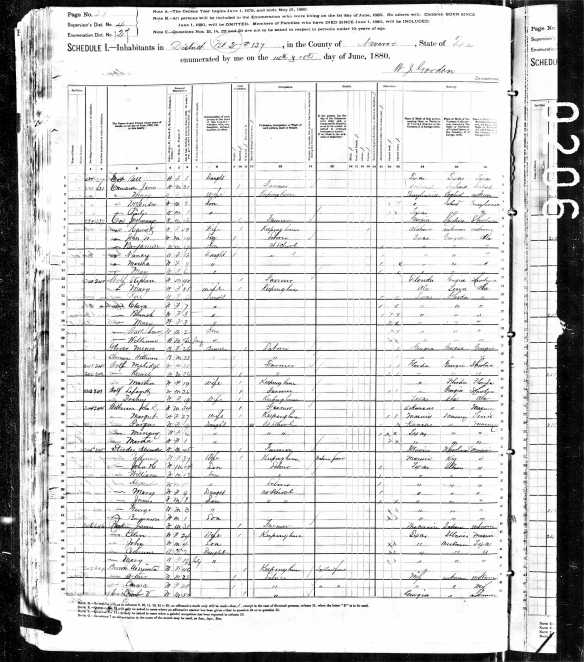

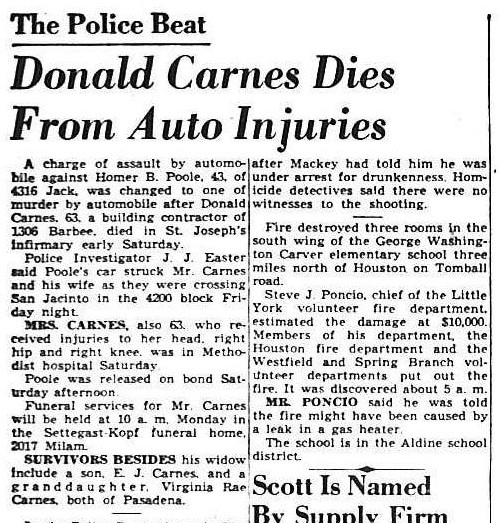

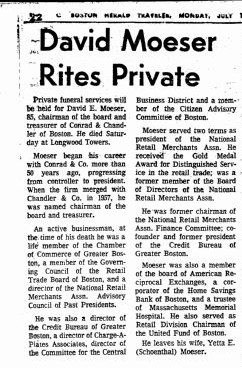

The tragic death of Flora Wolfe Goldman in 1910 was not the only loss that the Wolfe family would suffer during the decade of the 1910s. On December 27, 1913, Elias Wolfe died at age 74 from heart disease.

![Elias Wolfe death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/elias-wolfe-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=544)

Elias Wolfe death certificate

Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Sometime after Elias died, Amalie Schoenthal Wolfe moved to Middletown, Ohio, as she is listed in the Middletown city directory for 1917. Amalie obviously wanted to be closer to her only surviving daughter and her Ohio grandchildren.

Etta and Max Wise had four more sons after moving to Ohio: Richard Elias (1915), Max, Jr. (1917), Robert (1919), and Warren Harding Wise, born on September 19, 1920. I guess we know who Max and Etta (if she voted since the 19th amendment had just been ratified on August 19, 1920) voted for in the 1920 Presidential election—the native son candidate from Ohio, Warren Harding. I wonder how little Warren Harding Wise felt when he learned that his namesake was involved in the Teapot Dome scandal as well as other scandals, which were revealed in the years after Harding’s untimely death in office in 1923.

English: Warren G. Harding, by Harris & Ewing. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

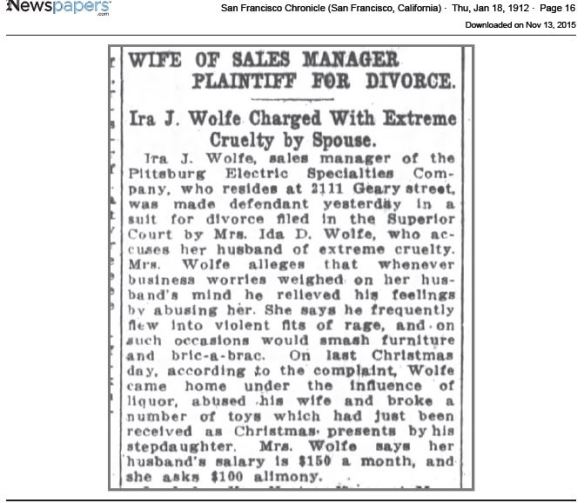

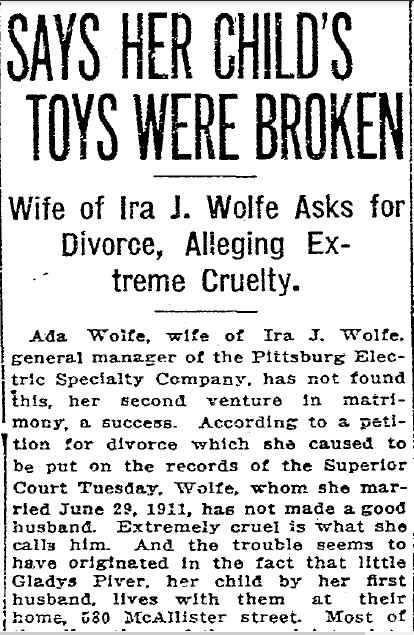

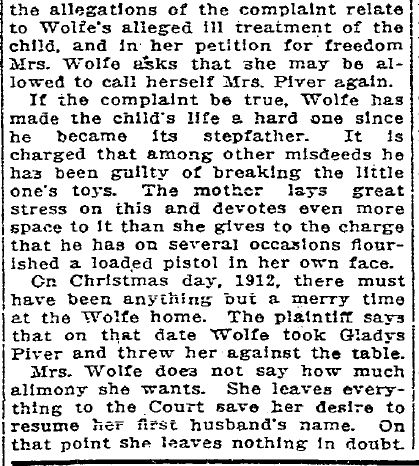

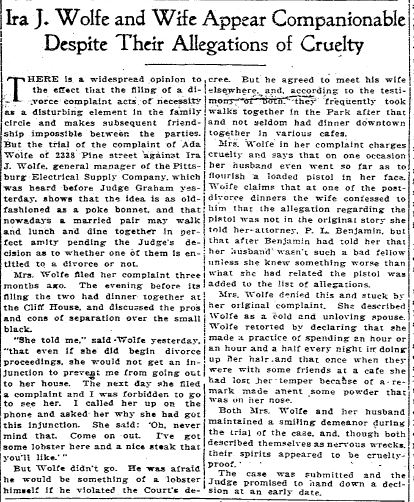

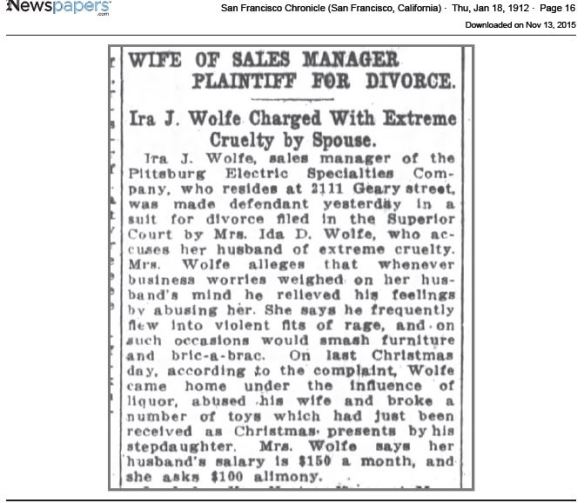

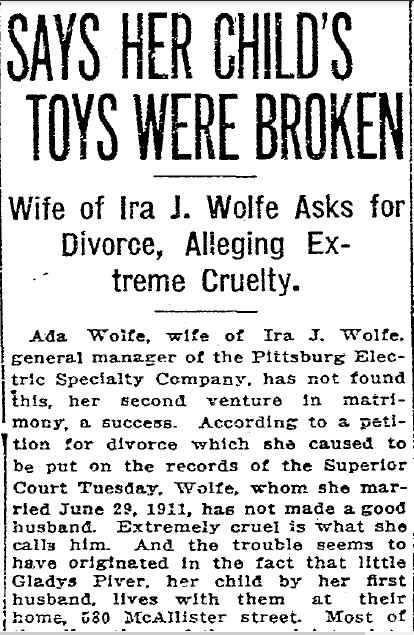

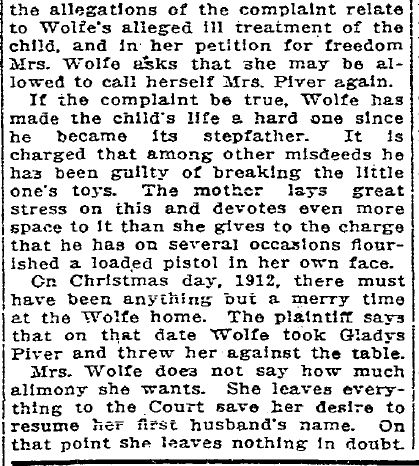

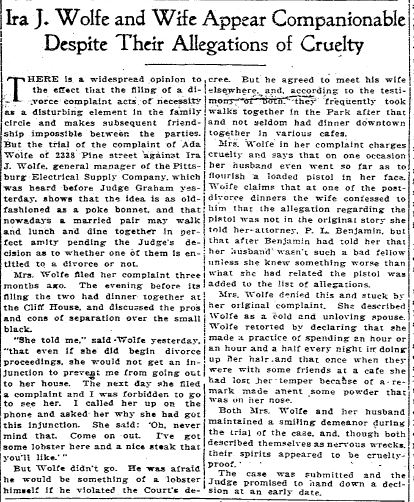

Meanwhile, out in California, Ira Wolfe was having his own troubles. On June 29, 1911, he married Ada Piver in San Francisco. Just over six months later in January, 1912, Ada sued him for divorce, claiming “extreme cruelty,” as detailed in these two news articles.

San Francisco Chronicle, January 18, 1912, p. 16

San Francisco Chronicle, May 15, 1913, p. 10

And if we think that social media and tabloids today have undermined all attempts at maintaining some privacy and dignity, this news article indicates that the public’s taste for gossip has always been a way of selling newspapers:

There’s no way of knowing the truth of Ada’s allegations (and I could find no follow-up story describing the court’s ruling in the case). Assuming there was some truth to her descriptions of Ira’s temper, drinking, and violent nature, perhaps it is not surprising that he had moved so far from his home in Pittsburgh.

Ira’s younger brother Herbert, still living in Detroit, married Elsa Repp on June 24, 1916. Elsa was a Detroit native, the daughter of John and Amelia Repp, who were also both American-born. In 1910, John Repp was working as a metal polisher, and Elsa was working as a box maker in a laboratory.

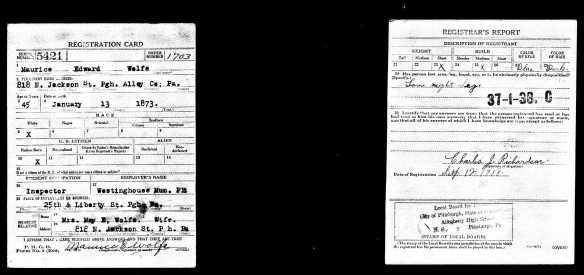

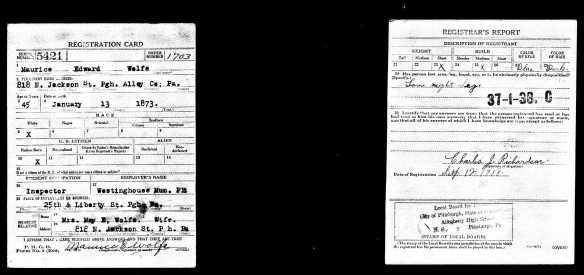

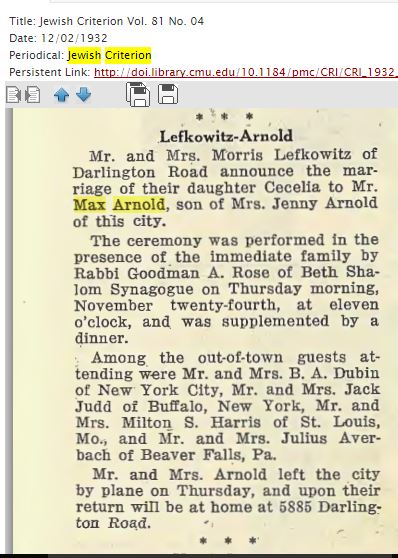

Back in the Pittsburgh area, only two of Amalie and Elias Wolfe’s children remained. Maurice Wolfe had married by 1917 according to his World War I draft registration. I’ve not been able to find anything about his wife’s background; all I know is that her first name was May and that she was born around 1880 in New York, according to the 1920 census record. In 1917, Maurice and May were living in Pittsburgh, and Maurice, who was lame in one leg, was working as an inspector for Westinghouse. As far as I can tell, they did not have any children.

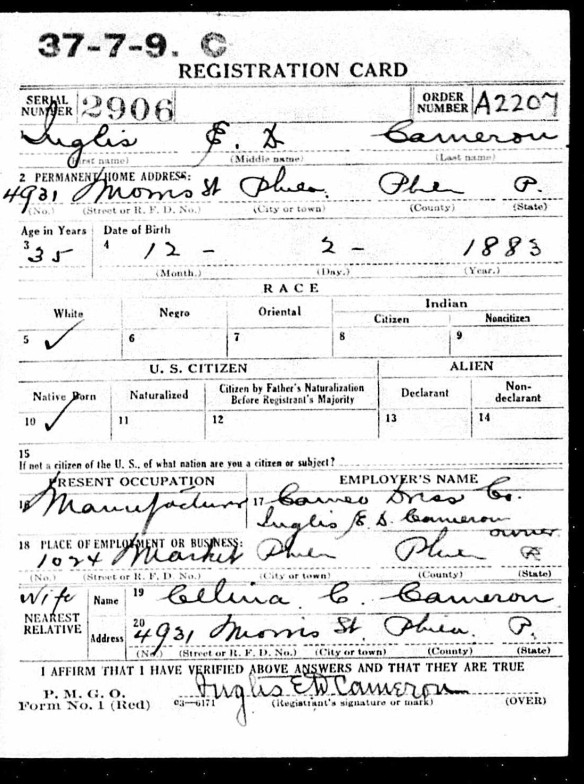

Maurice Wolfe World War I draft registration

Registration State: Pennsylvania; Registration County: Allegheny; Roll: 1909278; Draft Board: 18

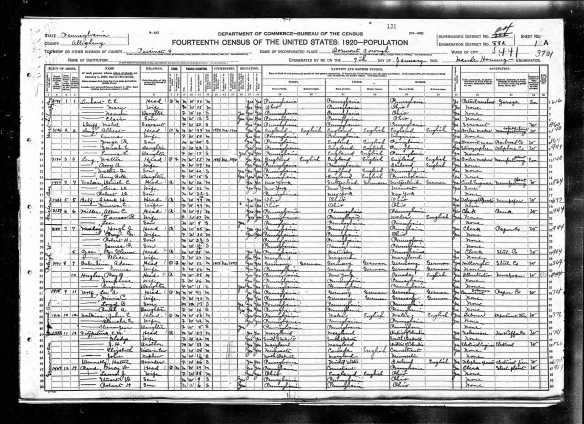

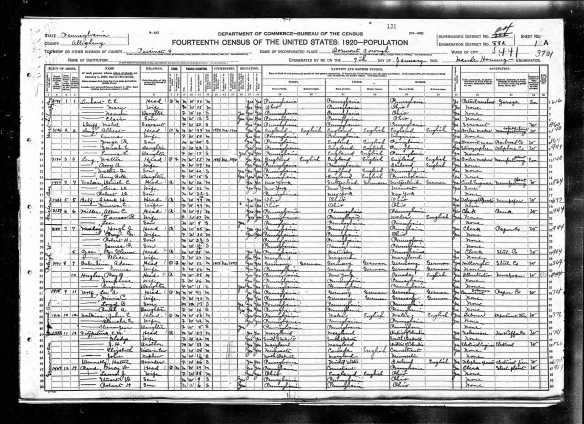

By 1917, Lee Wolfe and his wife Minnie had moved to Dormont, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Pittsburgh about four miles south. Lee was the local manager of the Interstate Folding Box Company. On the 1920 census, Lee, Minnie, and their two children, now teenagers, were still living in Dormont, and Lee was still working for a paper company as a commercial salesman.

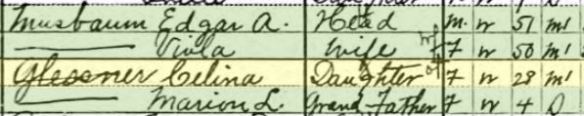

Lee Wolfe and family, 1920 census

Year: 1920; Census Place: Dormont, Allegheny, Pennsylvania; Roll: T625_1511; Page: 1A; Enumeration District: 882; Image: 267

Lee’s brother Maurice was also still in Pittsburgh in 1920, working as a government clerk, but by 1923 he had relocated to Middletown, Ohio, where his mother and his sister Etta were living. I cannot find Maurice on the 1930 census, but he was listed in the Middletown directory for that year. On the 1940 census, he was still in Middletown, working as a salesman, and divorced. Although I can’t be certain, I assume his marriage ended before he left Pittsburgh, but since I have no records for his wife May other than Maurice’s draft registration and the 1920 census, I can’t be sure.

In 1920, Max and Etta and their children continued to live in Middletown where Max was the proprietor of a clothing store. Herbert Wolfe and his wife Elsa were still living in Detroit where Herbert was now working as an installer for the telephone company according to the 1920 census.

Although Ira Wolfe was listed as a salesman in the 1917 San Francisco directory, I cannot find a World War I draft registration for him nor can I find him on the 1920 census. The last possible record I have for him is a listing on the Chicago, Illinois marriage index showing an Ira J. Wolfe marrying a woman named Agnes Resa on July 17, 1920. I did find Agnes on the 1920 census, taken before she married. She was thirty years old, born in Illinois, and living with her mother and brother in Chicago. Agnes was working as a comptometer for the railroad. What is a comptometer, I wondered? Apparently it was not itself an occupation, but a machine—a very early form of what today we would call an adding machine or a calculator. I assume that Agnes operated a comptometer for the railroad.

English: Comptometer – model E Français : Comptomètre – modèle E (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Thus, as of 1923, of the five surviving children of Amalie Schoenthal Wolfe, only Lee Wolfe was still living in Pittsburgh. Maurice and Etta were in Middletown, Ohio; Herbert was in Detroit; Ira was in Chicago. And Flora Wolfe Goldman’s children were living in Atlantic City, where Lehman and his family had moved by 1920.

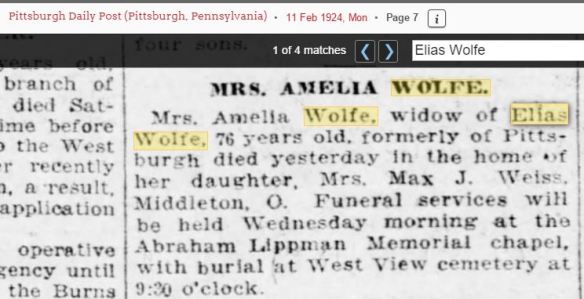

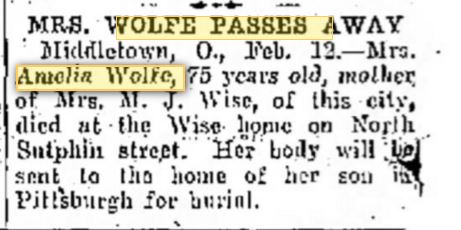

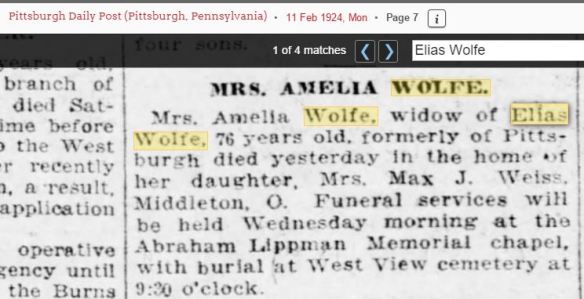

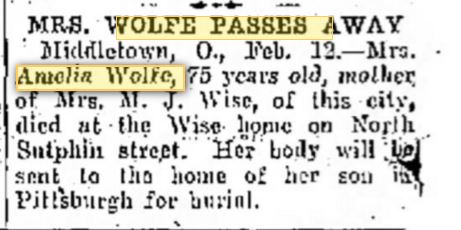

Their mother Amalie/Amelia Schoenthal Wolfe was living in Middletown when she died on February 10, 1924.

Hamilton (Ohio) Evening Journal. February 12, 1924, p. 2

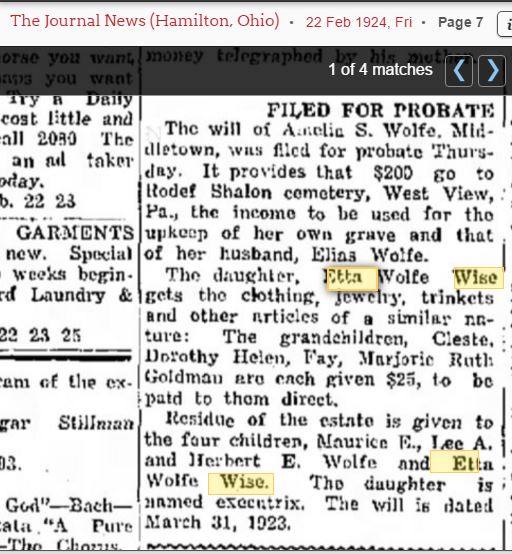

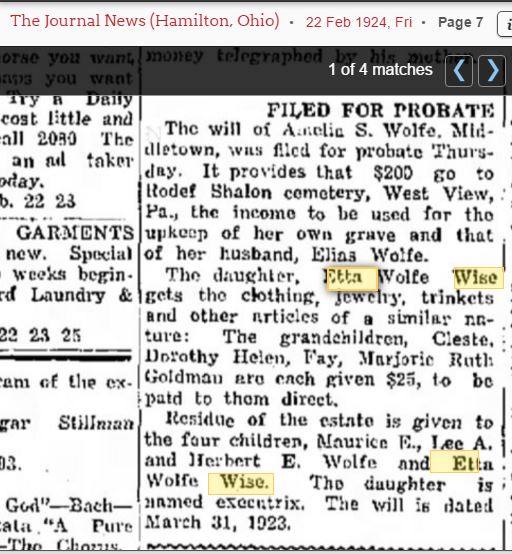

Just ten days later, her will was filed for probate:

I found this very interesting. I am not surprised that Amalie (or Amelia) left her personal property to her only surviving daughter Etta; after all, she had been living with her for many years. But I did find it surprising that she named her daughter Etta, not one of her sons, as the one to execute her will, in an era where men primarily took on such roles.

In addition, Amalie left $25 to each of her Goldman granddaughters—including Fay and Celeste, who were not even her blood relatives, but born to Lehman Goldman and his second wife Helen. Why not any of her grandsons? I understand why she only left the money to the Goldman grandchildren; since she was leaving the remainder of her estate to her surviving children, Flora’s children needed to be taken care of separately. But why not the boys? I’d like to think that Amalie was protecting the women in the family—making her daughter the executrix and only leaving money to her granddaughters. Perhaps she thought that the boys would be more able to take care of themselves in a world where women were still very dependent on men for support. I would like to think that Amalie, that adventurous young woman who had been eager to move to America , was somewhat of a feminist, treating her daughter and granddaughters favorably in her will to encourage their own independence.

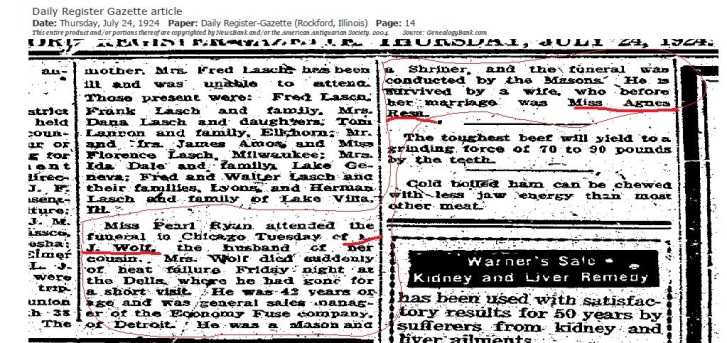

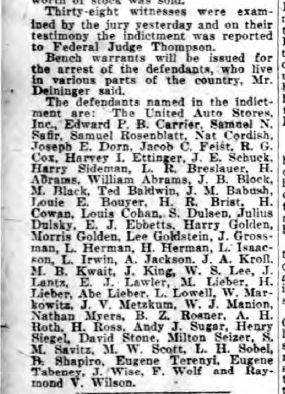

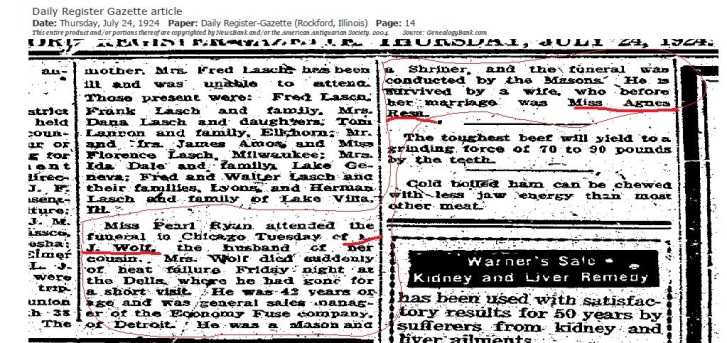

I also noticed that she did not include her son Ira as one of her five surviving children in her will. When I saw that, I assumed that Ira had been disowned or had died by the time of Amalie’s death. Then I found this news article on page 14 of the Daily Register-Gazette of Rockford, Illinois, dated July 24, 1924, five months after Amalie died:

This is clearly the same Ira J. Wolfe who married Agnes Resa on July 20, 1917, in Chicago. Can I be certain that this was Ira J. Wolfe, the son of Amalie and Elias Wolfe? According to the 1900 census, their son Ira J. Wolfe was born in June 1880, so he would have been 44, not 42, in July, 1924. Close enough? According to this article, he had been a general sales manager for a fuse company in Detroit; my Ira J. Wolfe had been a salesman for Pittsburgh Electric Company in San Francisco, so in the same field of electrical products. My Ira had a brother, Herbert, living in Detroit and then working for the phone company. Is this enough circumstantial evidence to support my assumption that the Ira J. Wolfe who married Agnes Resa and died in July, 1924, was the son of Amalie Schoenthal Wolfe? If so, he was still living when his mother Amalie died and thus was intentionally excluded from her will.

The 1930 census records for the surviving Wolfe siblings show that not much changed between 1920 and 1930. Lee was still in the paper business in Pittsburgh; his two children were now in their 20s. Lloyd, 28, was still living at home and working as a gas station attendant. His sister Ruth, 25, was also living at home and not employed.

Max and Etta were still in Middletown, Ohio, living with all of their children, who now ranged in age from nine to nineteen; Max still owned a clothing store. Etta’s brother Maurice was also still living in Middletown, as noted above. Herbert and Elsa continued to live in Detroit, where Herbert was a car salesman now. They had had a child in 1925.

As for the children of Flora Wolfe Goldman, by 1930 they were adults. Kenneth LeRoy (known as LeRoy K.) Goldman, Flora’s oldest child, was still living with his father and stepmother and half-siblings in 1930, working as a men’s clothing salesman. His sister Helen Goldman had married Bertie Kenneth Paget in 1926 and was living with him and their two year old daughter in Queens, New York, in 1930. Bertie was in the publishing business. Donald Goldman was living in Atlantic City in 1930 and was married to Marguerite Simpson; their daughter was born in 1931. Marjorie Goldman married John Lynn in 1929, and in 1930 they were living in Philadelphia where John was an insurance salesman. They would have two children in the 1930s.

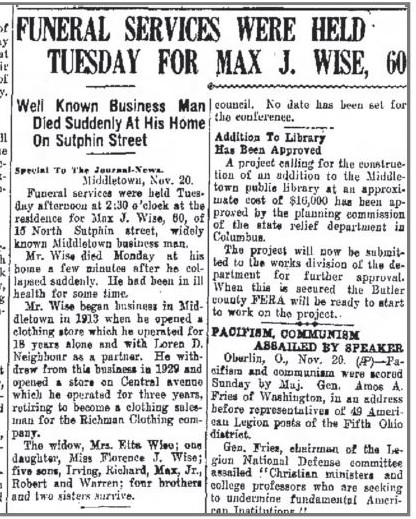

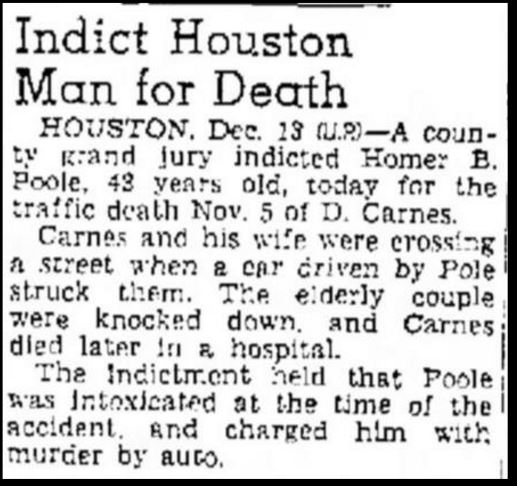

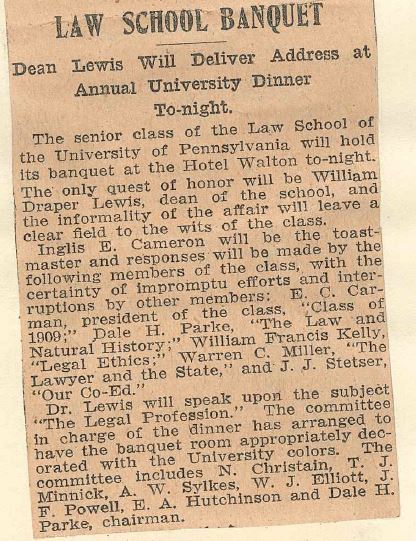

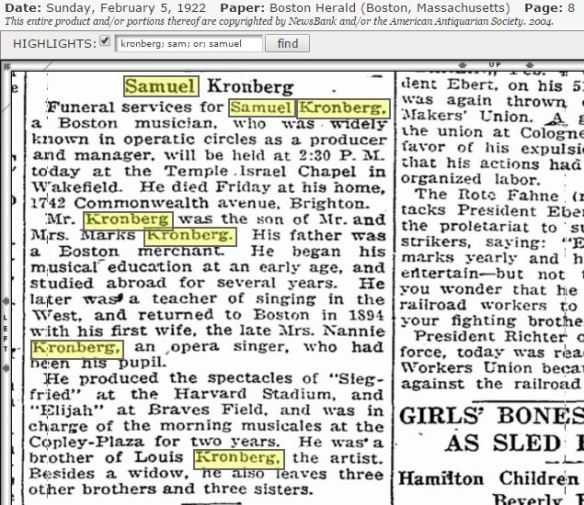

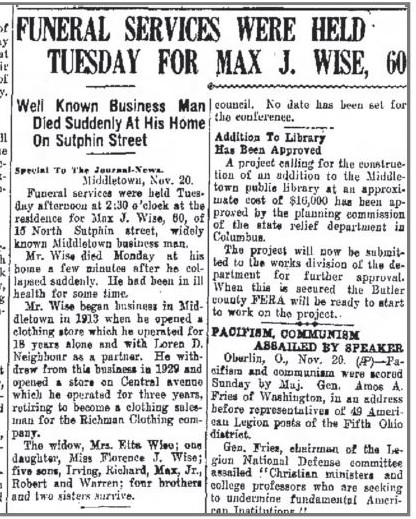

On November 19, 1934, Max Wise died at age 60:

Obituary for Max J. Wise,

The Journal News (Hamilton, Ohio) , November 20, 1934 p 2.

According to the obituary, Max had been in poor health, but died rather suddenly. He was survived by Etta, who was 50 years old, and his six children, who ranged from fourteen to 23 when they lost their father.

The 1940 census found all the remaining Wolfe siblings in the same locations as 1930: Maurice was in Middletown working as a salesman. Etta was also in Middletown with five of her six children still living with her; they all were now in their 20s, except Warren, who was 19. Only Irving had moved out; he was married and living in Miamisburg, Ohio, less than fifteen miles from Middletown. Lee Wolfe was still in Pittsburgh, still selling paper, and living with his wife and his two children, who were now in their 30s. Herbert continued to live with his wife and child in Detroit where he was the sales manager for the Detroit Auto Club. Thus, although the Wolfe siblings other than Lee had spread quite far from Pittsburgh, once they settled elsewhere, they stayed put.

Maurice Wolfe died in Middletown, Ohio, in 1941. His brother Herbert died in Detroit in 1951. Etta Wolfe Wise died in Middletown in 1957. Lee Wolfe lived to be almost 100 years old, dying in 1975 in the Pittsburgh area where he had lived his entire life.

Today we take for granted that our children will move away from the town where they were raised and that we will have to travel to see them. I sometimes wish for the “olden days” when children and grandchildren grew up in the same place where they were raised and multiple generations lived close by—whether it was a shtetl in Poland, a small town in Germany, or the Lower East Side of New York. I am sure I have romanticized the notion far beyond the reality. Nevertheless, it certainly was the general rule at least until after World War II that in many families, family members tended to stay put. My Cohen and Nussbaum relatives stayed for the most part in Philadelphia; my Brotman and Goldschlager relatives stayed in the greater NYC area.

The children of Amalie Schoenthal Wolfe seemed to be ahead of their times, moving far from home and from each other. I don’t know what motivated them all to move apart, but I’d like to think that it was the same spirit of adventure that led their mother Amalie, when she was still Malchen Schoenthal, to be the first sibling to express a desire to leave Sielen, Germany, and move to the United States to join her big brother Henry.

![Ancestry.com. Texas, Death Certificates, 1903–1982 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013. Original data: Texas Department of State Health Services. Texas Death Certificates, 1903–1982. iArchives, Orem, Utah.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/donald-carnes-death-certificate.jpg?w=584&h=477)

![Charles Cameron death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/charles-cameron-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=575)

![Title : New York, New York, City Directory, 1925 Source Information Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1989 [database on-line].](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/inglis-cameron-1925-nyc-directory.jpg?w=584)

![Ancestry.com. Texas, Death Certificates, 1903–1982 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/celina-nusbaum-carnes-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=481)

![Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/wolfes-in-1908-pitt-directory.jpg?w=584)

![Flora Wolfe death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/flora-wolfe-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=533)

![Elias Wolfe death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/elias-wolfe-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=544)

![Hannah Schoenthal Stern death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/hannah-schoenthal-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=548)

![Max Arnold, Sr. death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/max-arnold-sr-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=552)

![Jennie Stern Arnold death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/jennie-arnold-death-certificate.jpg?w=584&h=439)

![Louis W. Stern death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/louis-stern-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=436)

![Ancestry.com. U.S., School Yearbooks, 1880-2012 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/henry-schoenthal-ad-in-1892-w-and-j-yearbook.jpg?w=584&h=818)

![Duncan and Miller ruby pitcher By Nomoreforme at English Wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/georgian_ruby_pitcher_duncan.jpg?w=584&h=438)

![Washginton County Courthouse By Canadian2006 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/1024px-washington_county_courthouse_pennsylvania.jpg?w=584&h=438)

![1903 directory for Washington, PA Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/schoenthals-1903-directory-2.jpg?w=584)

![1905 directory for Washington, PA Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/schoenthals-in-1905-directory.jpg?w=584)

![Pittsburgh 1874 By Otto Krebs [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/1024px-pittsburgh_1874_otto_krebs.jpg?w=584&h=319)