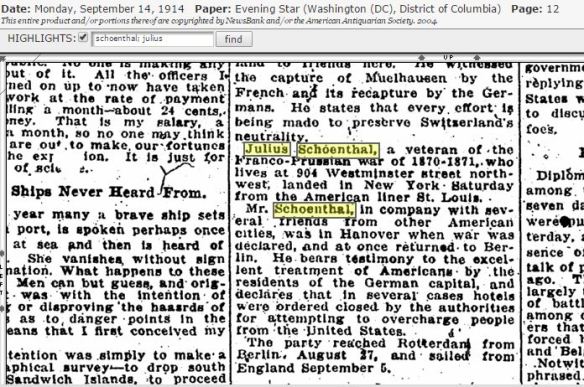

This was a major find, a discovery that has greatly inspired me and uplifted me.

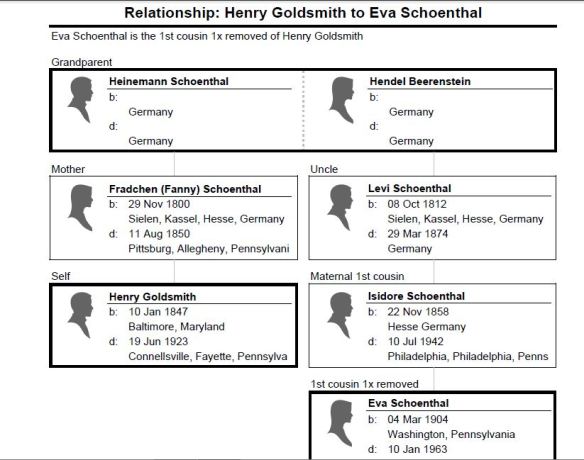

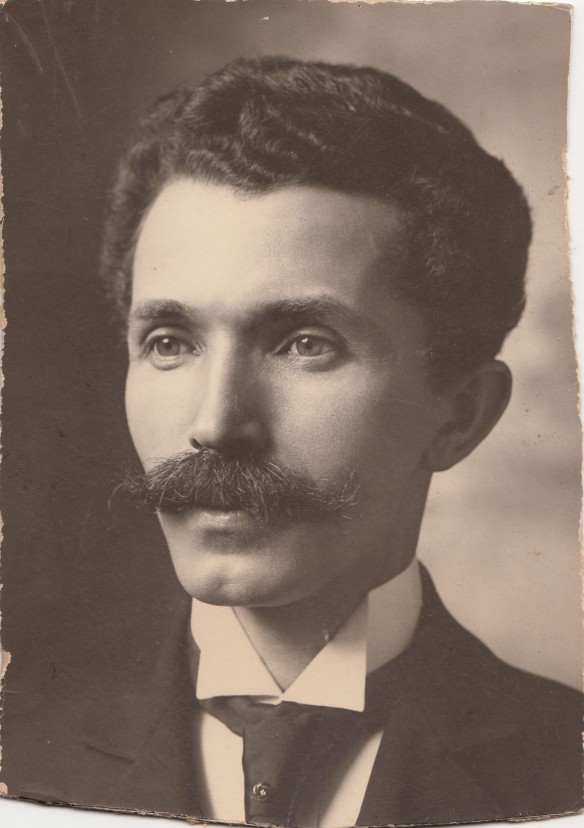

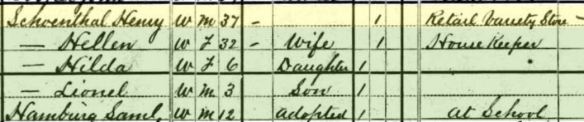

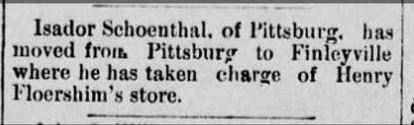

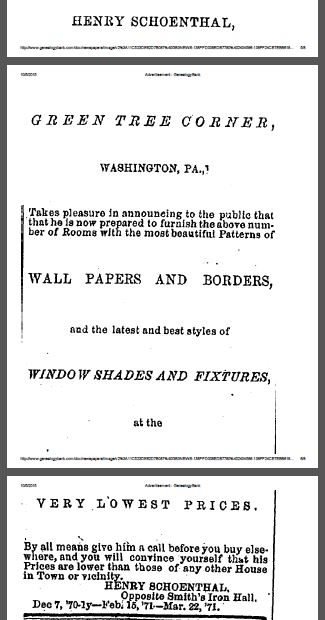

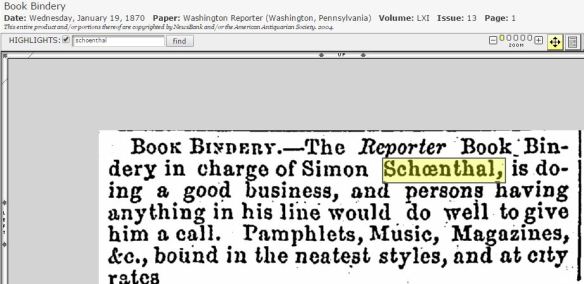

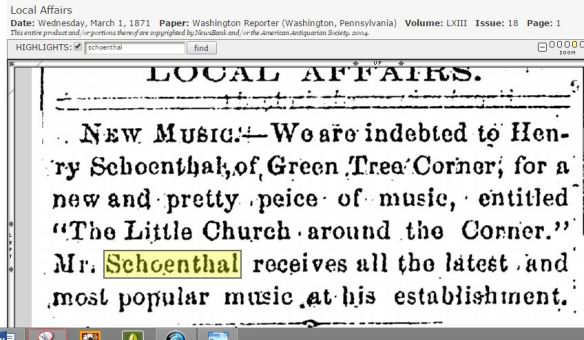

I’ve been researching the Schoenthals in depth for quite a while now, and I’ve been so fortunate to find as much as I have about the family both in German and American records. As I was preparing a post about Henry and Isidore, my great-grandfather, I decided to see if I could find a picture of Henry. After all, he was a prominent man in Washington, Pennsylvania for many years. There had to be a picture of him in a newspaper or archive somewhere. So I tried Google.

Unfortunately, I didn’t find a photograph of Henry. But what I found was amazing and did in fact give me a better picture of Henry. The Jacob Radosh Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, Ohio, had four entries for Schoenthal in its collection: three labeled Henry Schoenthal, one Hilda Schoenthal. They were titled as papers, a biography, a diary, and a sermon. I saw this the other evening and was excited, but had no idea how I could see these papers without going to Cincinnati. So the next morning I called the Marcus Center and spoke to an extremely helpful man there named Joe. Joe explained that they would scan all the pages of the documents for me for 25 cents a page and email them to me. There were forty pages in total, and so in less than hour and for only ten dollars, I had the four files in my email.

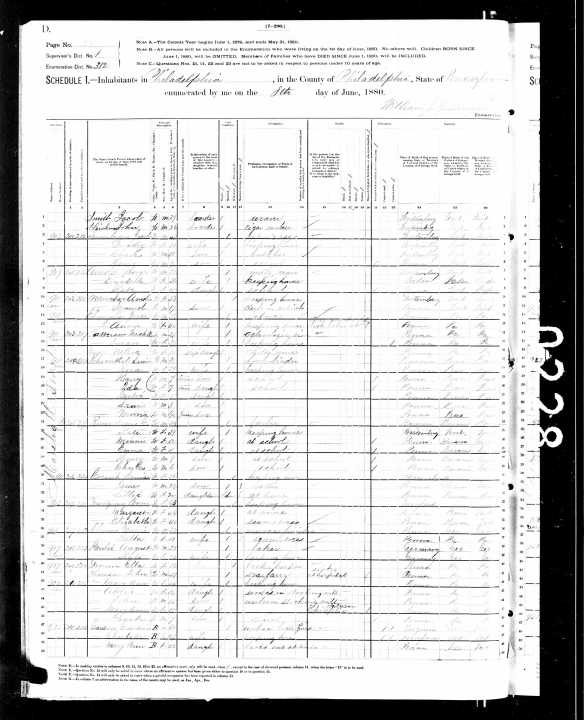

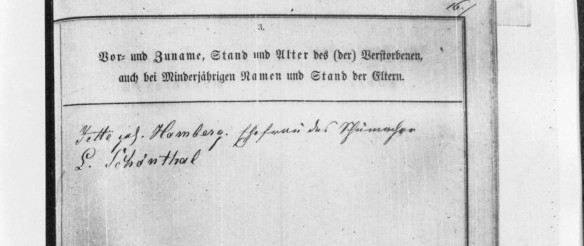

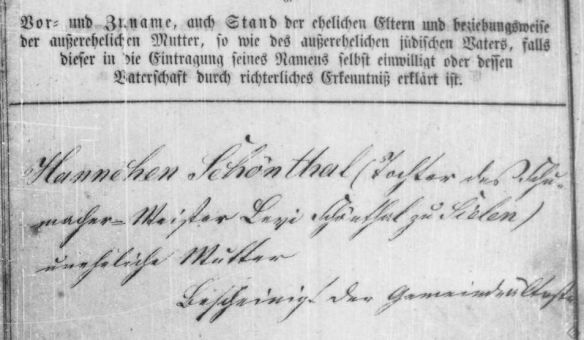

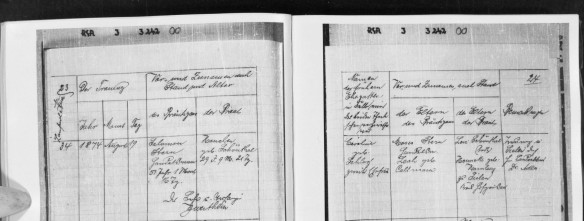

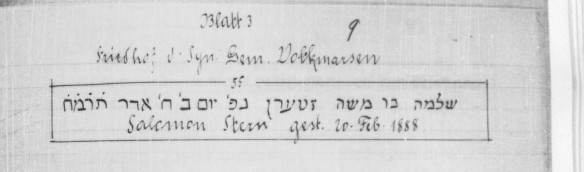

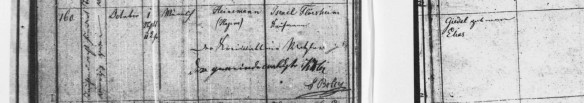

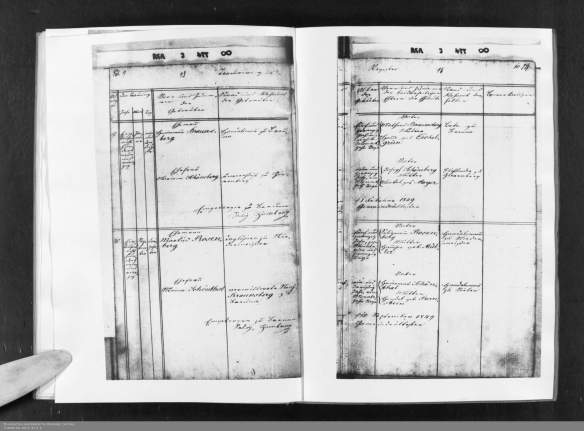

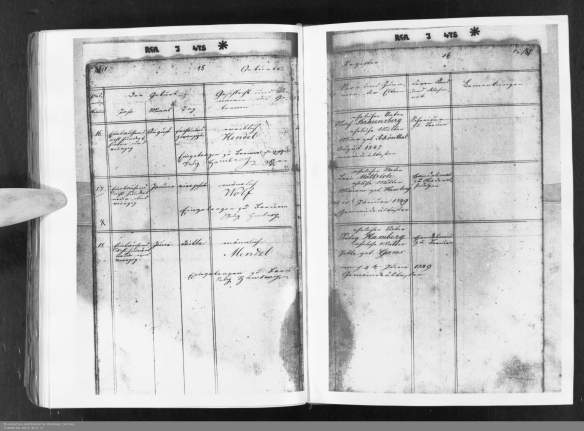

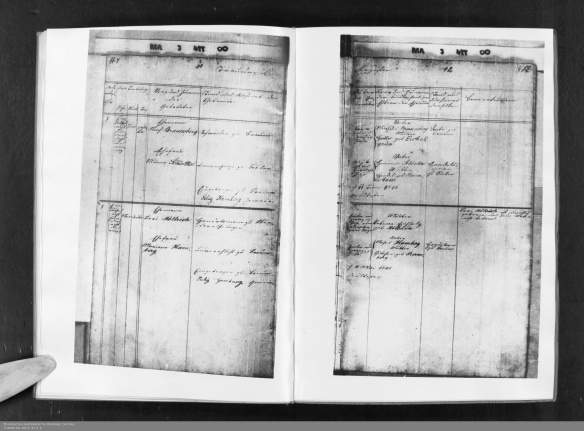

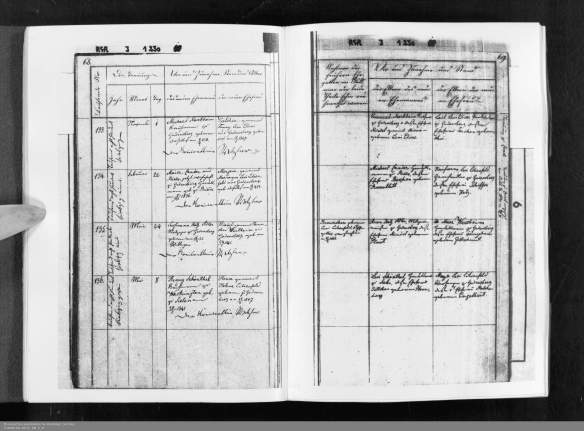

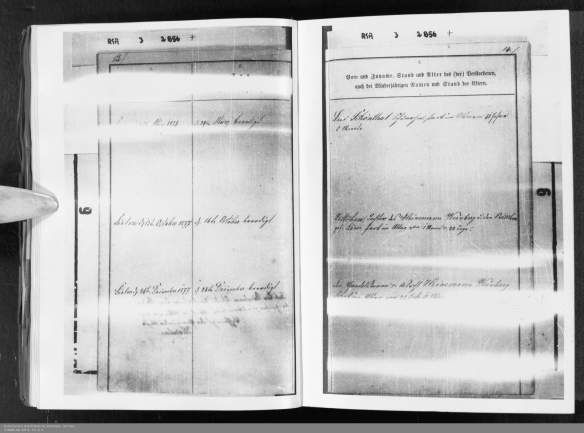

The folder of Henry’s papers, which date from 1863 to 1866, are in German. I am going to have to find someone to help me translate them. But here’s one that confirms Henry’s (then Heinemann) birth date and place and his father’s name; I think it is a certificate of his training to be a Jewish teacher at the seminary in Cassel, Germany:

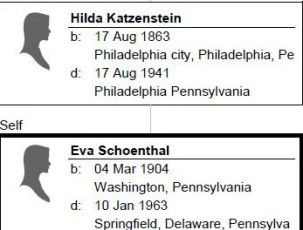

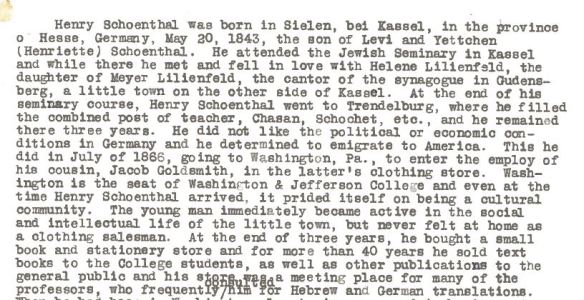

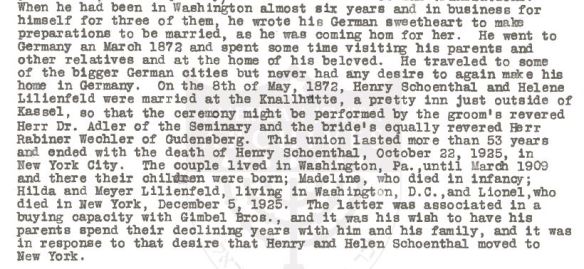

The biography is a one page biography of Henry Schoenthal written by his daughter Hilda in 1952. Although much of it was information I already knew, it adds another dimension to this man, making him come to life for me. I want to look first at the first section of that biography because it will provide greater background to the diary and to the sermon, the remaining two files I received.

Hilda Schoenthal, Biography of Henry Schoenthal dated January 16, 1952. Available at the Marcus Center, Cincinnati, Ohio

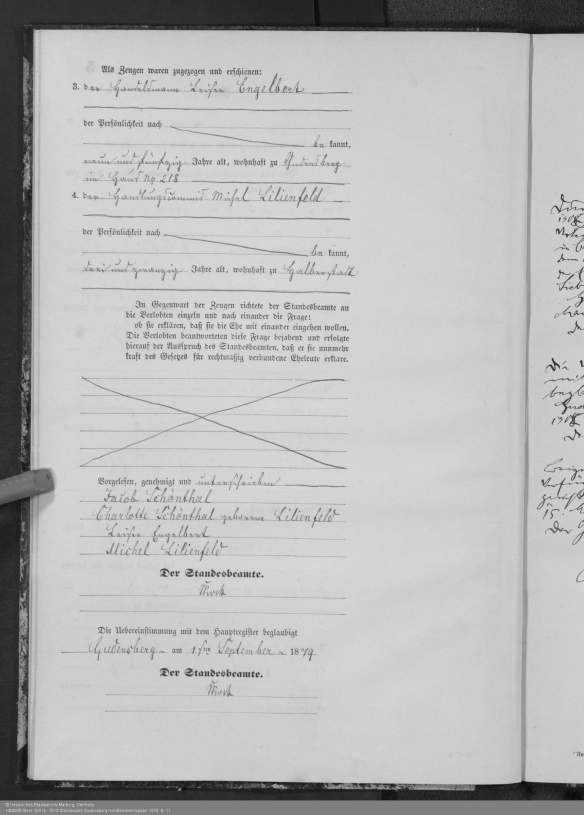

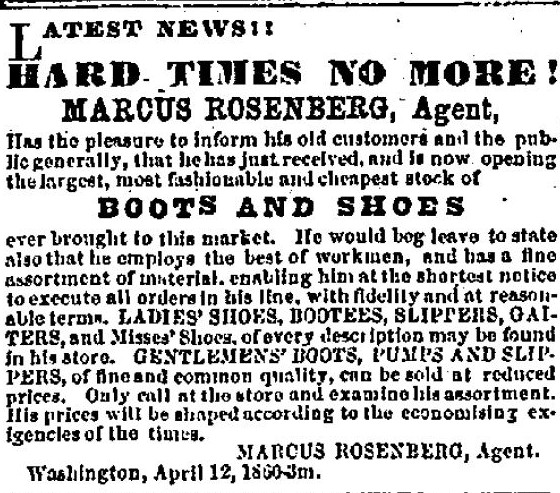

Again, although I knew most of the facts reported here, it was wonderful to read it in words written by Henry’s own daughter. I didn’t know how he met his wife or that her father, Meyer Lilienfeld, was a cantor. And I did not know that Henry was a shochet (kosher butcher) and a chazzan (cantor) as well as a teacher back in Germany. I wish Hilda had expanded on the political and economic conditions that drove her father to emigrate. And I found it interesting that Washington was considered somewhat of a center of culture and intellectual activity because of the presence of Washington and Jefferson College in the town. It also gave me a sense of Henry as someone interested in the life of the mind—someone who preferred selling books to students than selling clothing.

Western side of McMillan Hall on the campus of Washington & Jefferson College in Washington, Pa. .. Built in 1793, it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (Wikipedia)

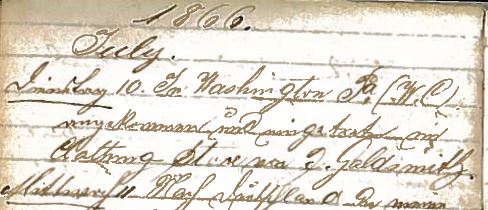

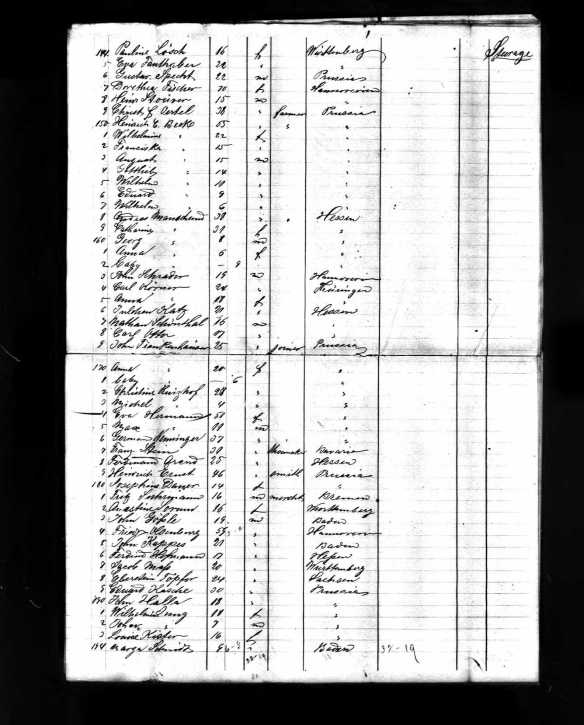

The diary, which starts in 1866 when Henry arrived in America, starts out in German, but after the first several pages, Henry began to write in English and to use script which I can read. Reading those pages was very moving, and I will share some of them below. Thanks to my friend Matthias Steinke, I was able to get the initial pages translated into English.

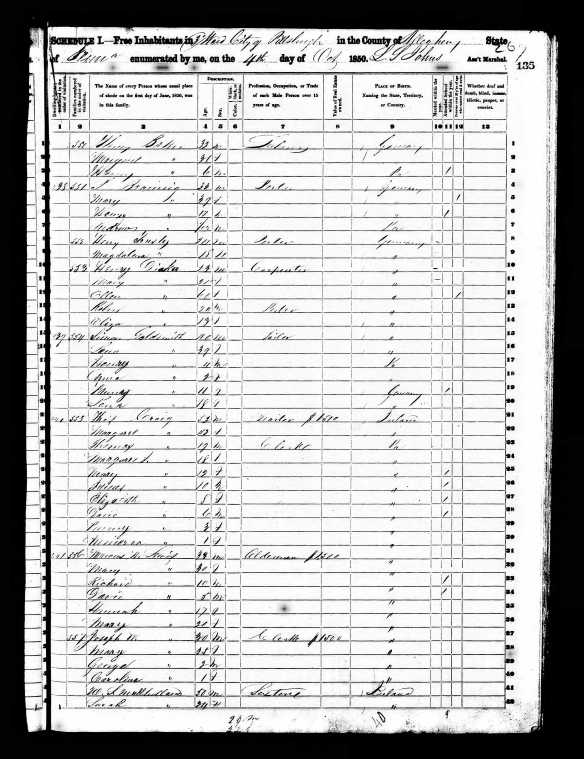

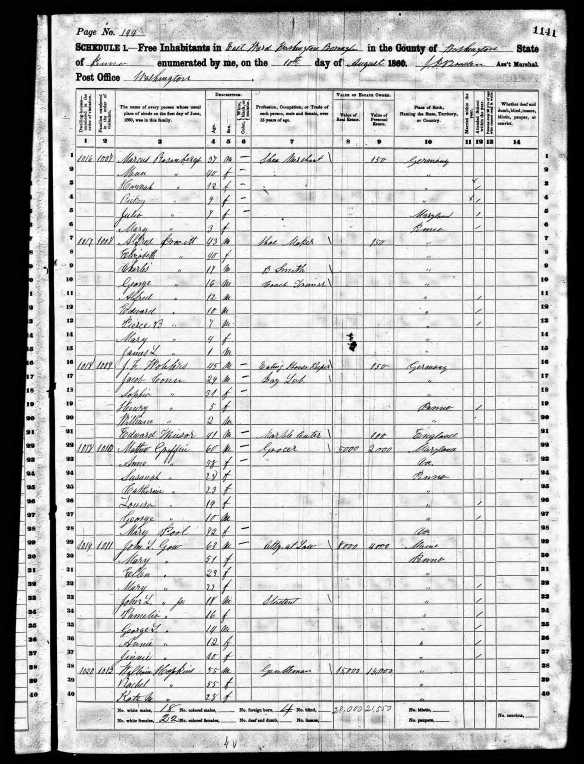

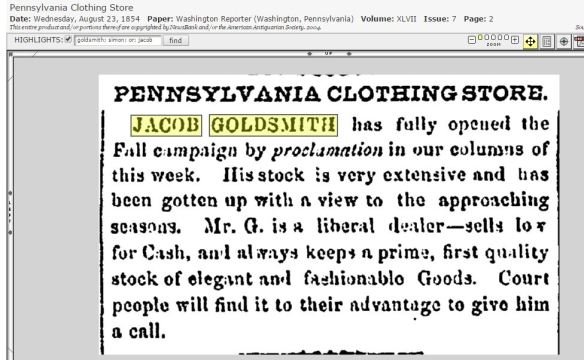

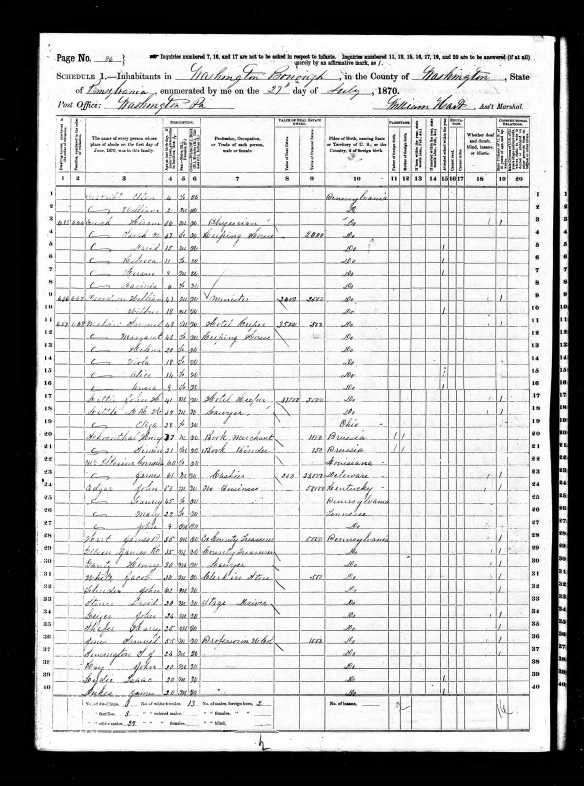

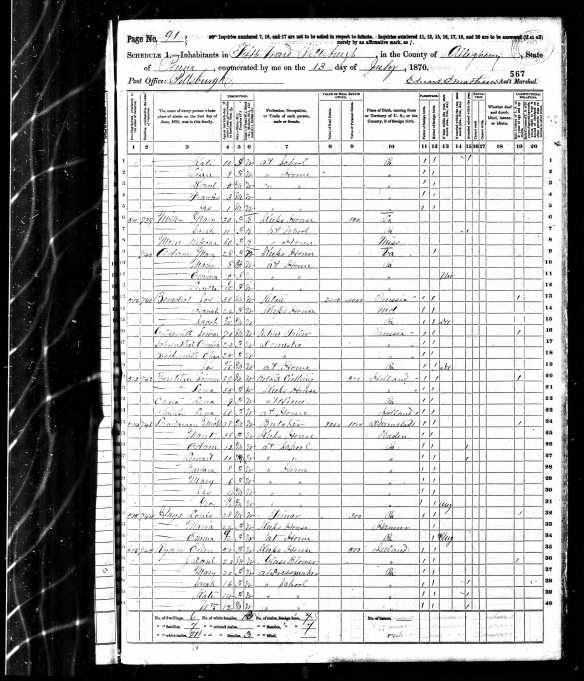

The diary begins on July 10, 1866, just a few weeks after Henry had arrived in New York, and says that he had just arrived in Washington, PA, and was working for his cousin Jacob Goldsmith in his clothing store (for some reason “clothing store” is written in English).

By the next day he had written to his parents and sent them three gold dollars. He did not receive his first letter from his parents until August 9th and immediately responded, sending them ten dollars in “greenbacks.” On August 16th, he described a visit from the Democratic candidate for governor of Pennsylvania, Hiester Clymer, and the fanfare surrounding that. Then there is a long entry about the some criminal activities going on in the town. Most of the pages in German report on his correspondence with various people back home.

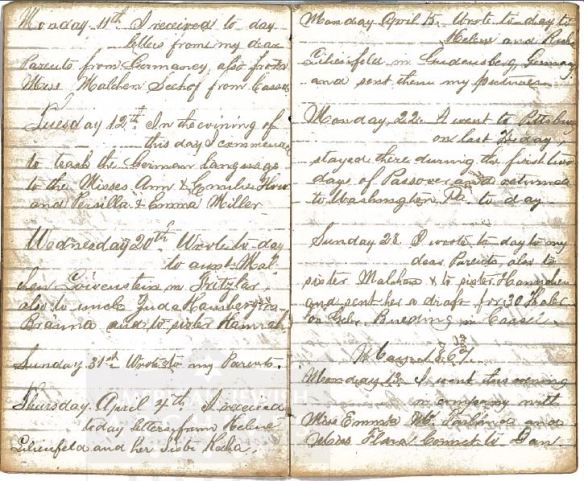

By January 1867, Henry was writing in fluent English. Just six months in the US, and he was already comfortable with and even preferring to write in English. I was impressed. Much of what he continued to write about was his correspondence— naming those to whom he had written and those who had written to him. This page, with several entries dated in April, 1867, I found particularly interesting.

On Tuesday, April 12, 1867, Henry mentioned that he was beginning to give German lessons to some residents of the town. On these pages, he also mentioned writing letters not only to his “dear parents” and sending them money, but also writing to his uncle Juda Hamberg from Breuna, who was his mother’s older brother, and to Helene and Recha Lilienfeld. Helene would later become his wife, and there are numerous mentions of correspondence between Henry and the two Lilienfeld sisters. On this page he also mentioned that he sent the Lilienfeld sisters his pictures. I sure wish I could see a copy of those pictures.

Of greatest interest to me on this page, however, is Henry’s comment on Monday, April 22, that he went to Pittsburgh “last Friday and stayed there for the first two days of Passover.” I was touched that Henry was making an effort to hold on to his traditions and heritage while alone without his parents and siblings nearby. Of his family members already in the US in 1867, the only one likely to have been in Pittsburgh was Simon Goldsmith, widower of Fanny Schoenthal and thus Henry’s uncle by marriage.

Although Henry may have had his heart set on Helene (also called Helen) Lilienfeld, he was not sitting home. He mentioned at the bottom of this page that in May 1867 he went to a show with a Miss Emma ? and a Mrs. Flora Conner (?) and did not get home until half past eleven.

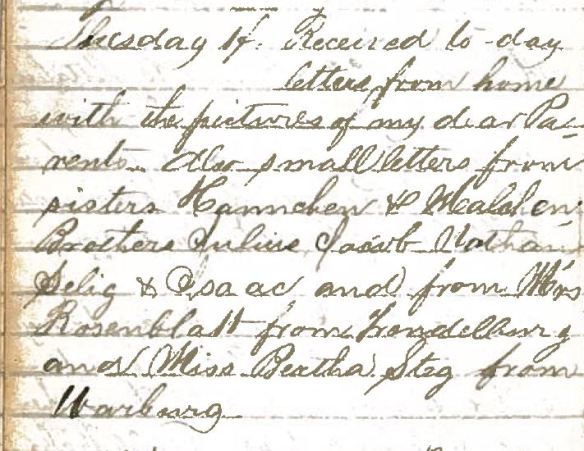

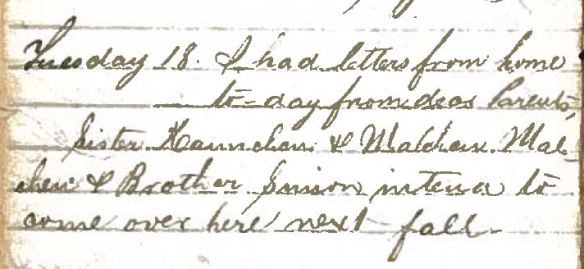

One of my favorite diary entries also is dated in May 1867:

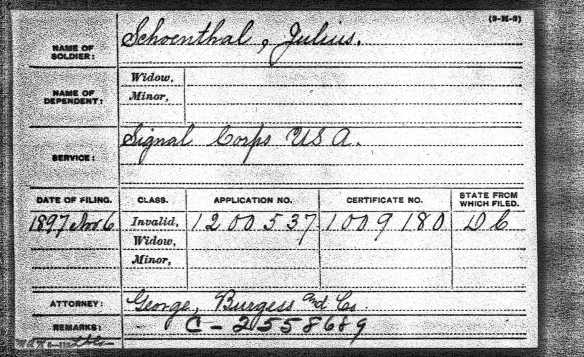

Why do I like this entry? Because it mentions my great-grandfather and by his original name, Isaac. Henry referred to all his siblings by their original names. Malchen was Amalie, Hannchen was Hannah. Selig became Felix. I also liked that Julius was listed, confirming once again that Julius Schoenthal was a sibling. I imagine Henry writing all those names and looking at the pictures his “dear parents” had sent to him and being somewhat homesick.

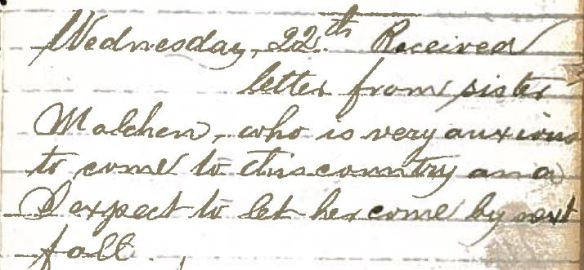

But there was some news to alleviate that homesickness. He mentioned on the next page that Malchen wanted to come to the United States. He said that she was “anxious to come to this country and I expect to let her come by next fall.” This seems to suggest that the decision was up to Henry, not his parents or his sister Malchen. Was this about money? Henry often mentioned sending money home to his family.

But on June 18, Henry wrote that his sister Malchen and brother Simon “intend to come over here next fall,” so perhaps he really did not have control over their decisions to emigrate.

Although Henry was continuing to correspond with “dear Helene” and her sister, he was also exchanging pictures with a Miss Therese Libenfeld in Frankfort and teaching German to several young women in Washington.

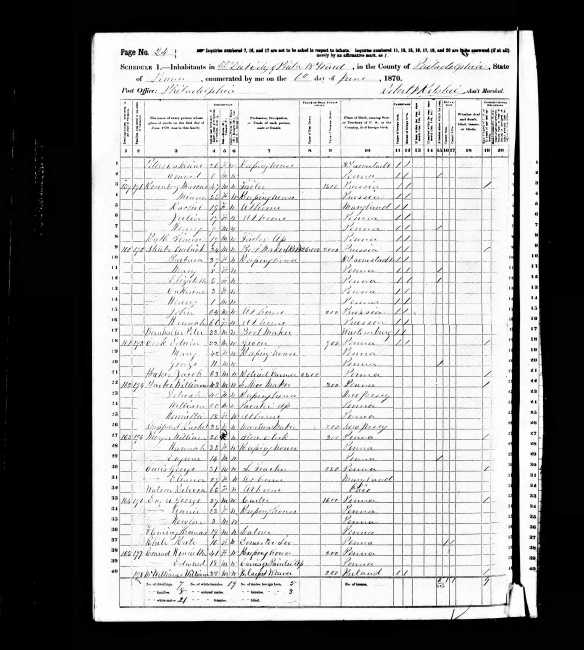

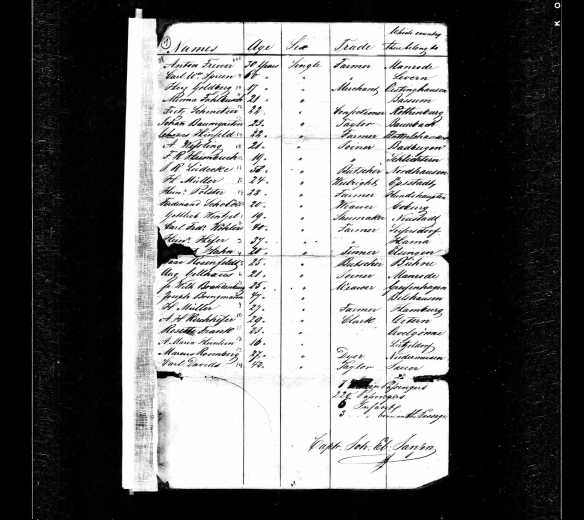

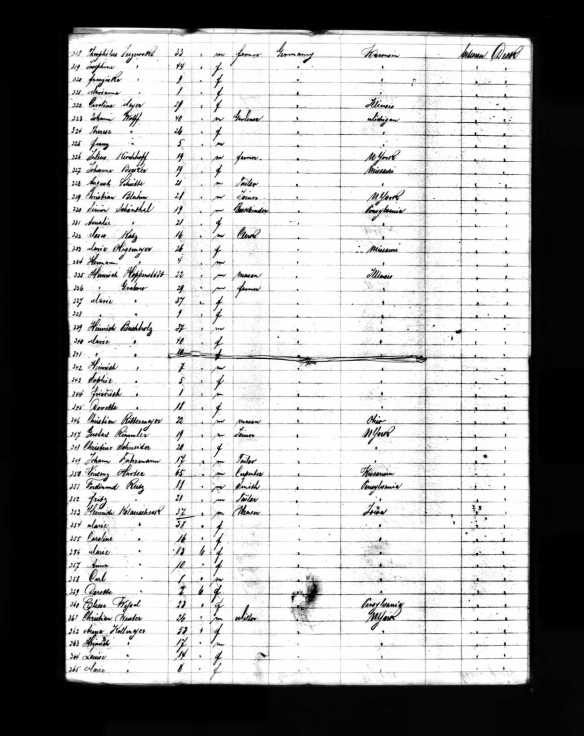

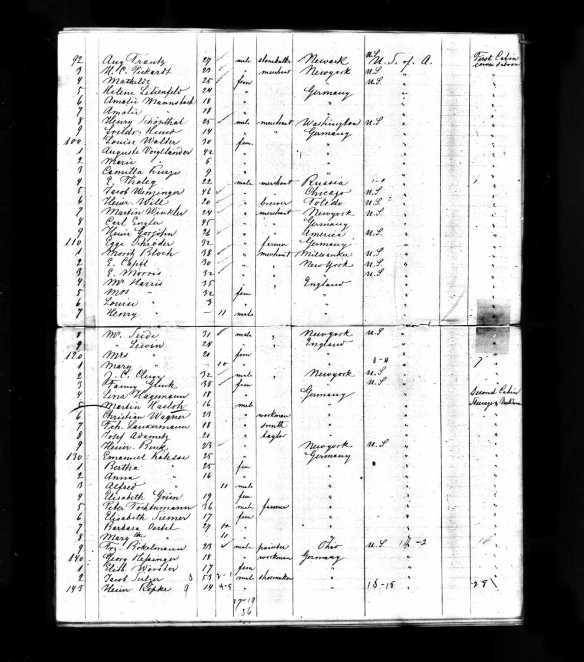

On September 9, 1867, Henry reported that he had received a letter from his parents informing him that his brother and sister, Simon and Malchen, had left Bremen on August 17 to sail on the ship SS Watchen. This is consistent with the ship manifest I found for Simon and Amalie, which has them arriving in New York on September 23, 1867. The only inconsistency is that the ship manifest record states that the ship was named Wagen, not Watchen. Close enough.

After that the diary peters out with very few entries between September 1867 and February 1868, the date of the last entry. My guess is that Henry was busy with his siblings, helping them to adjust to the new country, and perhaps less in need of keeping track of his correspondence.

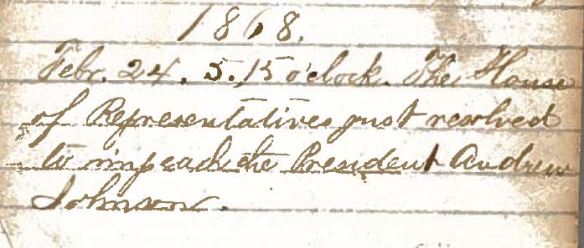

The very last entry, dated February 24, 1868, records a piece of US history. Henry wrote: “The House of Representatives just resolved to impeach President Andrew Johnson.” Unfortunately Henry expressed no opinion or reaction to this occurrence. Was it upsetting to him? How did he feel about American democracy? I wish I knew.

I loved reading the diary. Although it is not terribly intimate or revealing in its content, I can imagine this young man in his early 20s sitting down to keep track of everyone from back home with whom he corresponded. The fact that the diary ends shortly after the arrival of his sister and brother make me think that the diary’s purpose had at that point been served. Henry now had some of his family with him and no longer needed the ritual of the diary to help him feel connected.

Returning to Hilda’s biography of her father and her description of his life after 1868:

I found Hilda’s final paragraph particularly interesting:

This was not the image I had of Henry from the documents I’d found or even the newspaper articles. Henry wasn’t just a successful businessperson. He was a committed Jew working hard to create and maintain a Jewish community in this small town in western Pennsylvania. He was still a teacher many years after leaving Trendelburg, Germany, a man interested in books and students and Jewish traditions. Now I see a whole new dimension to this man who was my great-great-uncle.

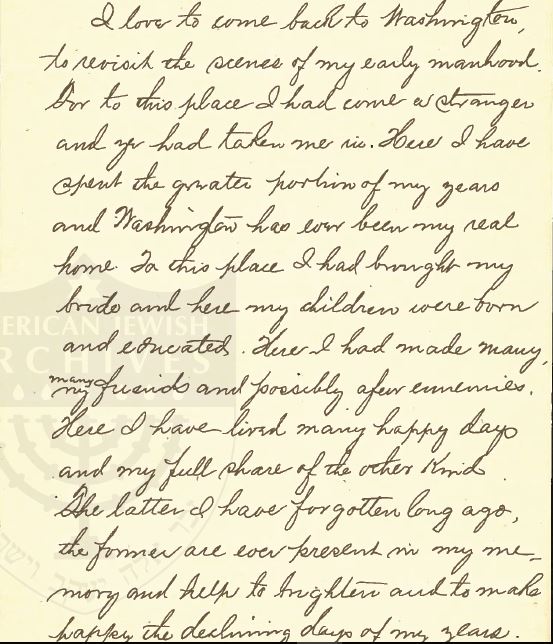

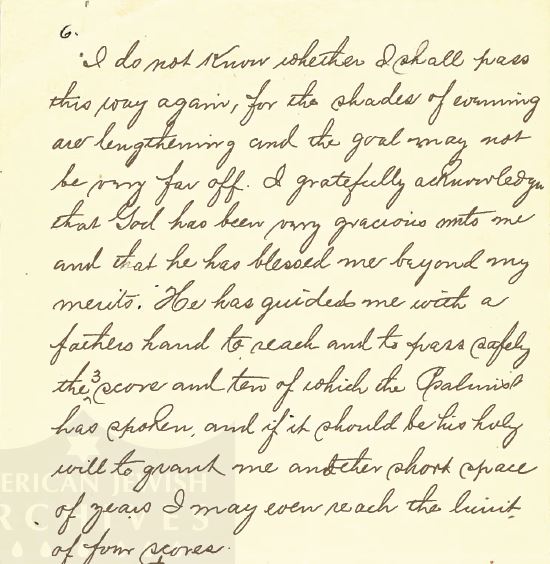

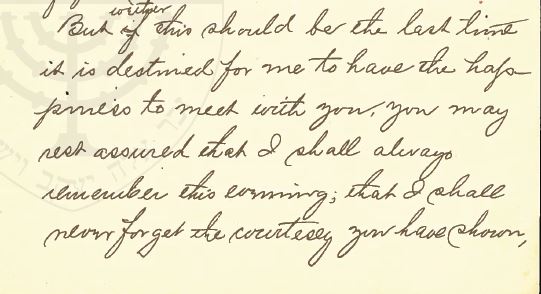

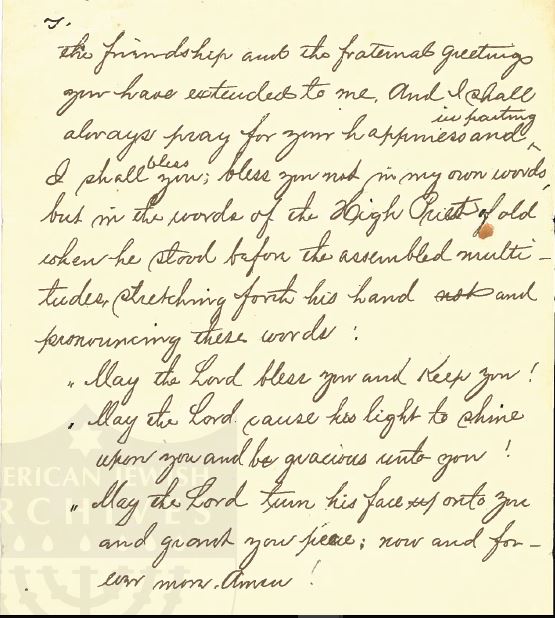

The remaining file that I obtained from the Marcus Center was the so-called sermon. For me, this was the most exciting document of all. The sermon was written by Henry in 1912, three years after he had moved away from Washington to live near his son Lionel in New York City, as mentioned by Hilda. Henry was by this time almost 70 years old. From what I can infer, the sermon or speech was to a fraternal organization in Washington given on the occasion of Henry’s return to Washington for a visit. I will quote the portions I found most touching and most revealing:

He wrote:

I love to come back to Washington to revisit the scenes of my early manhood. For to this place I had come a stranger and you had taken me in. Here I have spent the greater portion of my years and Washington has been my real home. To this place I had brought my bride and here my children were born and educated. Here I made many, many friends and possibly a few enemies. Here I have lived many happy days and my full share of the other kind. The latter I have forgotten long ago, the former are ever present in my memory and help to brighten and to make happy the declining days of my years.

I do not know whether I shall pass this way again, for the shades of evening are lengthening and the goal may not be very far off. I gratefully acknowledge that God has been very gracious unto me and that he has blessed me beyond my merits. He has guided me with a father’s hand to reach and to pass safely the 3 score and ten of which the Psalmist has spoken, and if it should be his holy will to grant me another short space of years, I may even reach the limit of four scores.

But whether this should be the last time it is destined for me to have the happiness to meet with you, you may rest assured that I shall always remember this evening, that I shall never forget the courtesy you have shown, the friendship and the fraternal feelings you have extended to me. And I shall always pray for your happiness and in parting I shall bless you, bless you not in my own words, but the in the words of the High Priest of old when he stood before the assembled multitudes stretching forth his hand and pronouncing the words:

May the Lord bless you and keep you!

May the Lord cause his light to shine upon you and be gracious unto you!

May the Lord turn his face unto you and grant you peace, now and forever more. Amen!

I admit that my eyes well up with tears every time I read and re-read these words. I am moved by so much of what he said here: his attachment to Washington, PA, as his home, a place that had welcomed a very young man in 1866 and given him a safe place to settle and work. He mentioned good times and bad, but overall his memories of this place are filled with love for the people he knew there. I feel his love for this place and for the people and his joy in being there and the sadness he feels in leaving it and perhaps not being able to return another time. We all have those feelings about places we have lived–whether it is a childhood home, a college campus, a first apartment. We move on, but a piece of our heart remains behind.

I am also moved by the beauty of his writing. It’s hard to believe that English was not his first language, as with my cousin Lotte. Henry’s writing is so poetic, so evocative. I read it with wonder.

And then Henry closed with the traditional priestly blessing read even today in Jewish prayer services and used as a blessing on many occasions in Jewish life. A blessing we said to our own daughters on Friday nights when they were children. A blessing that Jews have said and shared for centuries. I am moved knowing that my ancestor shared in this tradition as well.

Henry had left the seminary, but that experience had never left him. He remained, as his daughter said, committed to his heritage and proud of it. He remained a religious man.

Finding these papers was another one of many highlights in my continuing search for the story of my ancestors. They inspire me to keep looking for more and to keep telling the stories. Henry Schoenthal wanted history and traditions to continue, and I want his story to live on as well.

![Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/jennie-stern-death-certificate-jpg.jpg?w=584&h=439)

![Robert Steel Kann death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/robert-kann-death-cert.jpg?w=584&h=541)

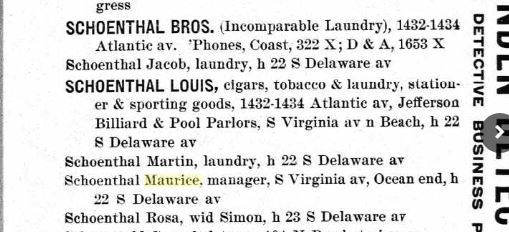

![Title : Washington, District of Columbia, City Directory, 1914 Source Information Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/schoenthals-in-1914-dc-directory.jpg?w=584)

![By Snapshots Of The Past (Parade Place and Kaufhaus Karlsruhe Baden Germany) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/parade_place_and_kaufhaus_mannheim_baden_germany.jpg?w=584)

![By Annaivanova (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/1024px-bechstein_576_grand_piano_franz_liszt_-_klavier.jpg?w=584&h=330)

![Irma Rosenfeld and daughter passport photo 1924 Ancestry.com. U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007. Original data: Selected Passports. National Archives, Washington, D.C.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/irma-rosenfeld-and-daughter-helen.jpg?w=313&h=213)

![p2 Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/doris-wiener-ship-manifest-p-2.jpg?w=709&h=267)

![By Zol87 from Chicago, Illinois, USA (Michael Reese Hospital) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/1024px-michael_reese_hospital_02.jpg?w=584&h=438)

![Washington, PA 1897 By Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler & James B. Moyer [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/old_fairgrounds_washington_pa_1897.png?w=584)

![Passenger manifest for Simon Goldschmidt, Fanny Schoenthal and Eva Goldschmidt Ancestry.com. Baltimore, Passenger Lists, 1820-1964 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006. Original data: Selected Passenger and Crew Lists and Manifests. National Archives, Washington, D.C.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/passenger-manifest-for-simon-goldschmidt-fanny-schoenthal-and-eva-goldschmidt.jpg?w=584&h=542)