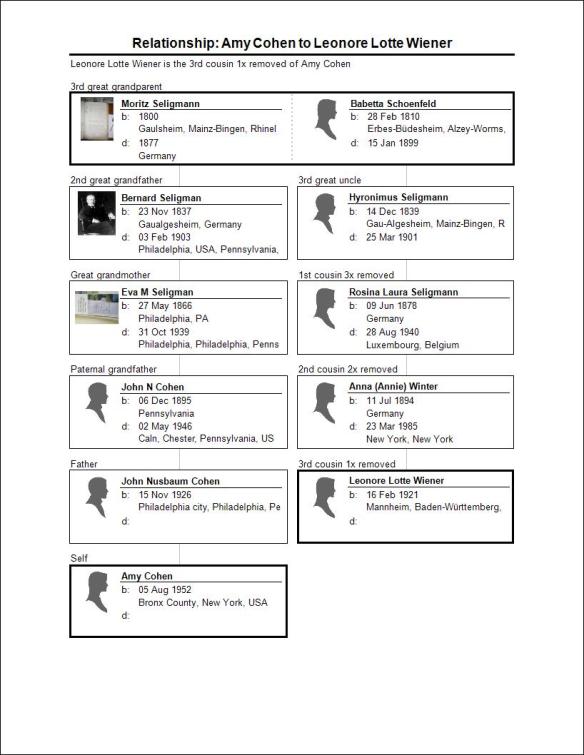

It has been a true blessing to connect with my cousin Lotte. Lotte is the daughter of Joseph and Anna (nee Winter) Wiener. Her mother Anna was the daughter of Rosina Laura Seligmann. Laura was the daughter of Hieronymous Seligmann, brother of my great-great-grandfather Bernard and son of Moritz and Babetta Seligmann, my three-times great-grandparents. Thus, Lotte is my third cousin, once removed. Her story is a remarkable story.

Lotte was born in Mannheim, Germany, in 1921, and she left Germany with her parents in the late 1930s to escape Hitler and the Nazis. Her education in Germany was cut short as a result, yet she came to the United States and successfully completed a nursing program in New York City shortly after immigrating. But I cannot do Lotte’s story justice. Fortunately, I do not have to because Lotte shared with me her memoirs and much of her other writing as well as some anecdotes she shared by email. With Lotte’s permission, I am going to share some excerpts from her own writing and some of those anecdotes.

I am also including a link to her memoirs for anyone who wants to read them in their entirety. You won’t be disappointed. Lotte’s writing is poetic, evocative, and very moving. This post will cover Lotte’s early life in Germany; subsequent posts will cover her life once Hitler came to power and then Lotte’s early years adjusting to life in the United States. (To read Lotte’s memoirs in their entirety, click on My Story Lotte Wiener Furst. Copyright Lotte Wiener Furst 2015. Not to be reproduced in whole or in part without permission of the author.)

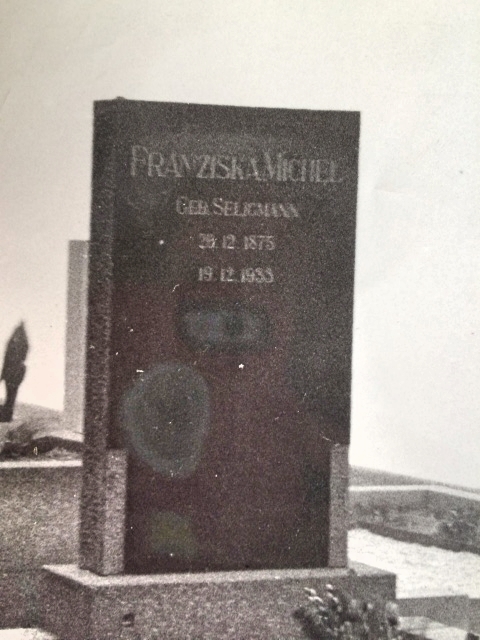

Lotte described her maternal grandparents Samuel Oskar Winter and Rosalind Laura Seligmann in these words:

My grandfather, born in Hülchrath, Westphalia, founded and owned a large dry-goods store. He had served his apprenticeship in a similar but larger store in Düsseldorf, having had to leave school at age fourteen because his mother was impoverished. He had a sister who never married, and a brother who later lived in Saarbrücken with his wife and two daughters, where he died quite young of syphilis. My grandfather was small of stature, but had a formidable mind and a keen, dry sense of humor. For quite a few years he served as a trustee of the local synagogue although he was not particularly observant.

My maternal grandmother was one of five siblings. Her family owned a vineyard in Gau-Algesheim, near Bingen, a place where my mother spent part of her childhood and which she always remembered very fondly. My grandmother also had left school at the age of fourteen in order to take care of her mother who was dying of tuberculosis, and to whom she had promised to always fast on Yom Kippur, and to observe Passover, promises she kept very faithfully. She loved poetry and could recite beautifully many of the sometimes very lengthy poems by the beloved German poets Goethe and Schiller. While my mother was growing up, my grandmother kept the books and otherwise assisted in the store. Keeping house was the task of Tante Yettchen, her spinster sister-in-law.

Laura Seligmann Winter with two of her sisters, Bettina Seligmann Arnfeld and Johanna Seligmann Bielefeld

Courtesy of Lotte Furst

Samuel and Laura Winter had two children, Lotte’s mother Anna and her uncle Ernst. Ernst was killed fighting for the Kaiser’s army in World War I:

My mother had one brother, Ernst, one year her junior. At the beginning of World War I he enlisted in the German army along with all of his classmates, much to the horror of his parents. He was killed six weeks later in the first Marne battle. My grandparents never recovered from the shock. I never saw my grandmother in anything but grey or black clothing. My uncle’s room was left untouched, and I was never allowed to enter it. My grandfather lost all his drive for maintaining the business, gave up his large store and became a partner in a much smaller one which was now mostly run by my grandmother’s brother, Uncle Jack, a very distinguished-looking but not very capable gentleman.

(“Uncle Jack” was Laura’s older brother Jacob, about whom I wrote here.)

How painful it must have been for Samuel and Laura to lose their son and then have the country he fought for betray them less than twenty years later.

As for Lotte’s mother Anna or Aennie, she was afforded a fine education as the daughter of a successful merchant:

My mother’s higher education consisted of a year or two in a finishing school, followed by some time in England where one of my grandmother’s uncles had established his residence. Her stay there was cut short, however, because this uncle, who owned several hotels and was very wealthy, made some unsolicited advances, and she fled in terror. The time spent in England provided her with an excellent chance to learn the language, which turned out to be quite an asset later on. She also was an accomplished pianist. Actually she aspired to become a concert pianist or at least a teacher of piano, but my grandparents felt that to be entirely inappropriate for a young lady of good bourgois upbringing. Their denial made her very unhappy but was mitigated somewhat when she received a beautiful black Bechstein grand piano as a wedding gift.

The uncle in England referred to above was, of course, James Seligman, born Jakob Seligmann, the younger brother of Hieronymous and Bernard Seligmann, the same James Seligman whose estate created quite a ripple of activity in the family and provided me with all those Westminster Bank family trees. Lotte also shared with me her own memories of James Seligman. According to Lotte, “[James] owned one or several hotels in Scotland/England. He lived in one of them. Together with his wife Hedy he visited his family on the continent once. She was a big and very pompous woman. After her death he visited the family again to distribute her belongings. Everybody went out of the way to serve him fancy dinners. My mother hired a caterer and we had “omelet surprise” for dessert. My grandmother Laura made a very simple home-cooked meal which he found the best he’d had. “

James married Claire, his second wife, shortly after his first wife Hedy died. Claire had been his nurse. When James died, Claire had the right to the income from his estate for her life; when she died, the principal was distributed to the various heirs found by the Westminster Bank. According to Lotte, her mother’s estate received $200 in 1985. I guess I can’t cry too much over the fact that the Westminster Bank failed to find my father and my aunt while doing their investigation since it seems their inheritance would have been about $100 each, if that much.

My heart went out to Lotte’s mother Anna Winter, a young girl with dreams of being a concert pianist, whose dreams were thwarted by society’s limited ideas of what a woman could be back in those times. Anna married Joseph Wiener in December, 1915. Joseph was in the Germany army at the time and was a doctor; after completing his service during World War I, he and Anna and their first daughter Doris moved to Mannheim where he established his medical practice. Lotte was born there a few years later during the years of the Weimar Republic.

Lotte’s description of her childhood home creates a vivid picture:

We lived on the second floor of a six story apartment building. There were two units on each floor. Our living quarters occupied one of these units while my father’s office and the maids’ quarters were situated in the other half. The office consisted of my father’s consultation room and a large waiting area where 20 – 30 chairs were lined up along the four walls, together with a coat rack and a spittoon. Doris and I shared one of the two family bedrooms, while the maids had to sleep in a very small and primitively furnished room, I am ashamed to say. They were not allowed to use our toilet, I am ashamed to say. … In addition to the maids, we had a part-time nanny and, for a few years at least, a part-time chauffeur who was mostly busy driving my father who had to make innumerable house calls. In 1923 or 1924 my parents had bought their first car, a black Benz, which unfortunately came to a sad ending when the chauffeur “borrowed” it for a joy ride and totally crashed it. The car was replaced by a green Buick, the driver was fired, and my father did his own navigating from then on.

****

Originally we had separate stoves in the various rooms, one of them a real pot-belly stove called “Der Amerikaner”. But in approximately 1928 my parents obtained permission to remodel our two apartments, and central heating was installed. The furnace, placed in the kitchen, had a large flat surface on which to keep pots of hot water and to make baked apples at times. It also provided a lot of soot. The noise of one of our maids stoking the fire early in the morning usually woke us up.

The living room featured three wall-to-ceiling bookcase units, separated by two bay windows. There was a wealth of information in those books, and my parents placed no restrictions on our choice of reading material. I devoured almost everything: fiction, classics, history, you name it. But I certainly did not retain most of the material I read. Other furniture included three caned armchairs, a round coffee table with marble top, a green velvet-upholstered sofa, and a large oak desk.

A doorway, equipped with a curtain, led to the dining room half a small step above. For a while Doris and I used this setting to put on some improvised shows. The oak dining room table was large and massive. Other than for dining we used it as an improvised ping-pong table when extended. Of course the proportions were not right, and the ball would bounce off when it hit the extension crack in the middle.

… My parents’ bedroom had mahogany furniture and yellow wallpaper with green and red intertwined garlands. I would stare at them at the times when I was allowed to lie on Mutti’s bed when I was sick, and I thought they were ugly. Doris’ and my bedroom was not so fancy. It was equipped only with two iron beds, a dresser, a night stand, and a clothes closet.

Between the bedrooms was a bathroom, used only for bathing. We had a separate toilet a little further down the hall and next to the kitchen which featured to a stove, oven, furnace, table and two chairs and an icebox, later replaced by a Frigidaire which was usually kept locked.

![By Snapshots Of The Past (Parade Place and Kaufhaus Karlsruhe Baden Germany) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/parade_place_and_kaufhaus_mannheim_baden_germany.jpg?w=584)

Mannheim, Germany By Snapshots Of The Past (Parade Place and Kaufhaus Karlsruhe Baden Germany) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

My father (Vati) was a very busy general practitioner. He had long office hours and also made numerous house calls every day, frequently to people who lived on the fourth, fifth or sixth floor of walk-up apartments. Elevators were non-existent in the working-class neighborhood where we lived. But he was always home for lunch, the main meal of the day, which was served at 1 PM. Breakfast was not a family affair – Doris and I had rolls with butter and jelly, delivered fresh every morning from the bakery across th street, and a cup of tea before leaving for school which started at 8 AM. During morning recess we had a “second breakfast” consisting of a sandwich which we brought from home. The light evening meal was served at about 7 PM.

My mother (Mutti) attended to the household: instructing, supervising and hiring and firing the maid(s), and doing the marketing which in itself was a very complicated job. Because many of the nearby merchants were my father’s patients, she had to keep track of with which grocer, which butcher, which baker she had done business last in order to keep all of them happy. Butchers were especially difficult. There were some who had the best and most aged beef, suitable for roasts, and some who carried a poorer quality and therefore were only good for meat that had to be boiled or braised. Sausage came from other sources: regular, ordinary sausage was bought at a nearby store, but kosher sausage with its distinctively different taste came from a Jewish butcher who lived quite a distance away. Vati frequently questioned where the meat came from, and Mutti, quite peeved, would answer “from the fish store”.

In addition to the household chores, Mutti kept my father’s books. At the beginning of each calendar quarter she had to add up all the patients’ slips pertaining to their insurance coverage, and submit them to the local health insurance office and to the few private insurance companies involved. Since Bismarck’s time in the 1880’s Germany had compulsory and comprehensive health insurance laws covering most of the working population. Self-employed and professional people took out their own private insurance. During those busy quarterly events Mutti was extremely nervous and tense. We knew better than asking her any silly questions.

After lunch, Vati usually took a short nap on the living-room sofa, followed, at least in the early years, by a cigar which I helped him light. He then resumed his afternoon office hours while I went back to school or to my music lessons or other activities. At some time during the afternoon I did my homework, never too much of a chore, and practiced my violin music for which I did not need any coaxing because I enjoyed it.

Lotte and her sister spent school vacations visiting Anna’s parents Laura (Seligmann) and Samuel Winter in Neunkirchen:

My grandparents’ (Oma and Opa’s) house had four stories: a large basement with a fruit cellar, a downstairs “salon” and formal dining room with a large veranda which was hardly ever used, another floor with the actual living quarters (living room, bedroom, bathroom and kitchen), and three more bedrooms above that. The rooms were rather small, however. A rarely used dumb waiter connected the kitchen with the downstairs dining room. A mostly unkempt and unplanted backyard, except for some large clumps of rhubarb, was also featured. The house overlooked a large and frequently used soccer field.

There was not very much to do at the house. I usually accompanied Opa to the store where he spent most of his time. The salesladies and the office help all were very nice. They gave me odds and ends of fancy yarns, remnants of cloth, and various sundries. The secretary let me use the typewriter where, one index finger at a time, I would compose never to be published letters and poems.

Oma meanwhile would be busy with her household chores. Once a week she attended meetings at a housewives’ club, and I would come with her whenever I was visiting. I believe they did some charitable work, but all I know for sure is that they gossiped a lot and always had a big “Kaffeeklatsch”. Every time they saw me, some of these ladies would ask whether I remembered who they were, followed by “my, how you have grown”. The club was the only outside activity Oma allowed herself.

![By Daniel Arnold (Photo taken by Daniel Arnold) [CC BY-SA 2.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/de/deed.en), GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/1024px-neunkirchen-am-brand-erleinhofer-tor.jpeg?w=584&h=437)

Town Gate, Neunkirchen By Daniel Arnold (Photo taken by Daniel Arnold) [CC BY-SA 2.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/de/deed.en), GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

My grandmother, Oma, was a fairly short, fairly plump woman. Her body, always dressed in rather shapeless grey clothes and bulging a bit in the center, did not seem to have any remarkable form of its own. But her oval face was kind and full of expression. Severely myopic, she had protuberant grey eyes. To help her poor eyesight, she used a lorgnette for reading. I don’t recall her ever wearing glasses. She also suffered from rheumatic heart disease, the result of rheumatic fever early in life, which incapacitated her a lot and finally contributed to her death.

To maintain her wavy, well-coiffured hairdo, Oma allowed herself the only luxury I was aware of. Once or twice a month she used the services of a hairdresser who came to her home to wash and set her hair, embellished by the use of a hot iron. She probably coordinated those appointments with the meeting dates of the “Hausfrauenverein” ( housewives’ club), a gathering of mostly Jewish old – or so it seemed to me – women who fairly fell over me when Oma took me along during my visits, exclaiming how I had grown and wondering if I still remembered their names. Whether the club members did anything socially worthwhile I do not know. I suppose they did. But I do know that they gossiped a lot while enjoying afternoon coffee and cake.

Oma’s most remarkable talent was her gift to recite poetry. With only a grade-school education, she had managed to memorize a great many of the famous German poems written in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, noticeably poems by Goethe, her hero, and also by Schiller. A glorified picture of Goethe adorned a wall in her kitchen, leading, to her bemusement, to a question by her milkman who wondered if that handsome man had been her father.

For more on Lotte’s grandparents and their home, read MY GRANDPARENTS HOUSE by Lotte (Copyright Lotte Wiener Furst 2015. Not to be reproduced in whole or in part without permission of the author.)

Lotte, an exceptional student, also wrote about her early school experiences:

From first through fourth grade I attended the Hildaschule, the public school for girls in the district where I lived and about three blocks from our apartment. My first impression of the first grade classroom was that it smelled bad and was very noisy, featuring an enrollment of about 40 anxious little girls. The teacher was very strict – a real no-nonsense person by the name of Mrs. Seltenreich. The slightest kind of misdemeanor was usually punished by a sharp blow with a cane on the poor kid’s outstretched fingers. It required a great deal of courage to oblige her. I must admit that I never was in that predicament since I was a very good little girl. But I had one great shortcoming: From the very beginning my handwriting was very poor. I never earned anything better than a “3″ (on a scale of 1-5) in that course. Later, when we started to write with ink, I did not produce one paper without a smudge or an inkblot. I never could shake that weakness, and only with the advent of the computer did I learn to produce more or less perfect papers without any visible corrections.

Mrs. Seltenreich was replaced by Fräulein Unger from second to fourth grade. She was a very kind, stout elderly lady who really loved teaching, trying some innovative methods, thus commanding respect without the cruelty shown by her predecessor. I had one girlfriend at that time but did not spend much time with her. Once I accompanied her to the Catholic church across the street from the school, and she showed me how to make the sign of the cross and how to kneel, which I did because I did not know any better. When I told my mother, she instructed me never to do that again. I, however, knew hardly anything about my own religion except for the fact that I was Jewish and therefore different.

School hours were during the morning. In the afternoon I usually went to a park with my nanny during the early school years. There I mostly played by myself or perhaps with one other child, sheltered kid that I was. In school we also had to attend an outdoor playtime session once a week. I did not like it too much because I did not know the games which most of the girls had played frequently. I was rather ignorant in social skills and did not participate very well.

In fourth grade I befriended a girl by the name of Johanna who lived on a river boat which made periodic stops in Mannheim, traveling up the Rhine from Holland. During those stops she attended my school. I proudly presented her to the handicrafts instructor (embroidery, crocheting and knitting were compulsory and part of the curriculum), only to be asked if she was also a Yid (which she was not). My mother was infuriated when I told her about this, so much so that she went to the School Board to complain. After all, we were living in Germany during the time of the democratic Weimar Republic. Discrimination supposedly was not allowed. I never found out if the teacher was reprimanded.

Reading this made me realize how drastically German society changed once Hitler came to power. Here was Lotte’s mother, a Jewish woman, daring to complain about an anti-Semitic remark made by a teacher. Just a few years later such anti-Semitism was the official law of the land.

After her early years in the girls’ school, Lotte was one of a small number of girls who were admitted to the almost all-male Karl-Friedrich Gymnasium, where she had to work extra hard and even box some of the boys in order to prove herself and win approval from her teachers. Lotte also spent many hours in the nearby art museum. She loved music and was exposed to music throughout her childhood. She started taking violin lessons when she was eight years old and had the same teacher for nine years until she and her family emigrated.

Although her grandmother Laura always fasted on Yom Kippur and observed Passover, as she had promised her mother, Lotte grew up with very little exposure to Judasim. She wrote:

Prior to the Nazi rise to power I had a very cursory knowledge of the fact that I was Jewish. My parents were totally non‑religious. They agreed with Karl Marx that religion was “the opiate of the masses”. My father even resigned from the Jewish community since he did not see why he should pay the obligatory cultural tax. In school I was listed as “without religious affiliation.” None of the Jewish holidays were observed at our house.

But Lotte’s grandparents and other relatives of her grandmother Laura did provide her with some knowledge and experience with Jewish rituals and holidays:

But at my grandparent’s house I learned a little more about Jewish customs. My grandmother fasted on Yom Kippur. They only ate matzot during Passover. Best of all, they had a blue and white KKL (Jewish National Fund) box on their living room chest. Only pennies were inside, as I found out when I tried to fish out the money with a crochet hook (I always replaced the money, I only did it because 1 was utterly bored and had nothing else to do). But I do remember the outline of Palestine on the box, and I learned that it was the Jewish homeland far away.

![Gilabrand at en.wikipedia [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/kkl_tin.jpg?w=584)

Gilabrand at en.wikipedia [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)%5D, from Wikimedia Commons

Lotte told me that the bar mitzvah boy was Heinz Goldmann, son of Anna Seligmann and Hugo Goldmann. Anna was the daughter of August Seligmann, my three-times great-uncle. Anna, Hugo, and their children were all killed in the Holocaust.

Overall, Lotte’s description of her childhood suggests that she had a very happy and comfortable childhood: a childhood free of economic or other struggles, a loving family, vacations and trips, school and art and music, and grandparents whom she adored. All of this would come to what must have been a shocking, heart-wrenching, and tragic end as Lotte entered adolescence and Hitler came to power.

![y Sg647112c (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/256px-table_of_consanguinity_showing_degrees_of_relationship.png?w=584)

![By Citynoise (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/coefficient_of_relatedness.png?w=584)