Will you help me solve a mystery?

The next page in Milton Goldsmith’s family album was devoted to his stepmother, Francis (sometimes spelled Frances) Spanier Goldsmith. But his story about her background and childhood left me with quite a mystery.

Milton was fifteen when his father remarried, and from this tribute to Francis, it is clear that he was extremely fond of and grateful to her.

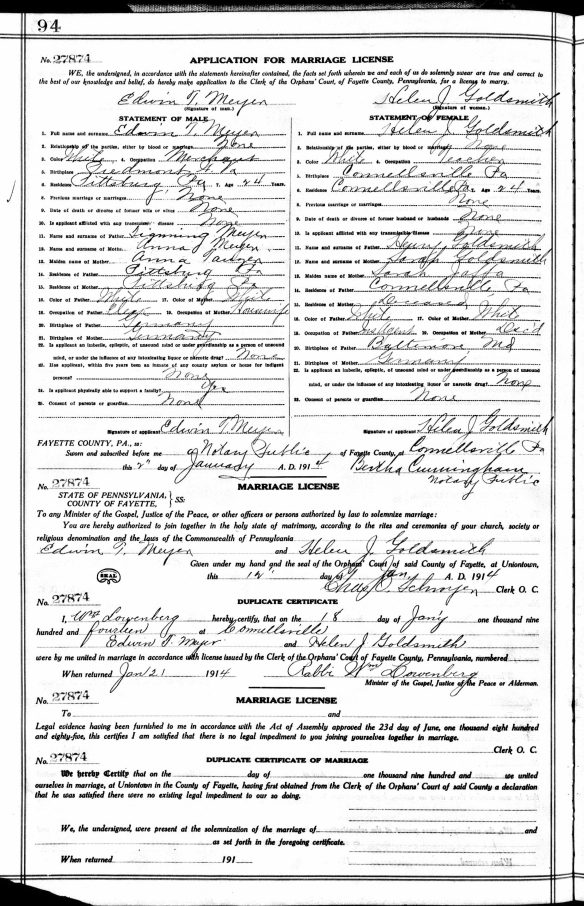

Francis Spanier Goldsmith, the second wife of Father, Abraham Goldsmith, was born in Germany in 1854. Left an orphan at an early age, she was brought up in the home of Rabbi Krimke of Hanover, Germany. At the age of 20 she came to America, and having an Uncle, Louis Spanier, living in Washington, D.C. she went there for a while but soon settled in Baltimore, and became friends with our cousins, the Siegmunds. It was there that father met her, having been introduced by Mr. S. Father had been a widower for two years with five young children to bring up, and was looking for a wife, a lady with no relatives. He fell in love with Miss Spanier, proposed after two days and married within two months. She was 22 and he past forty. She was an attractive girl, dark-eyed, brunette, speaking a cultivated German but very little English;- of an amiable disposition. Father’s greatest mistake was to keep the parents of his first wife in the house. This naturally led to friction. A brother, Julius Spanier soon came in our home and lived there for a while. Later a sister, Rose, came from Hanover and also lived with us for several years. She eventually married and lived in Birmingham, Ala, where her brother also made his home. Within a year the oldest son, Alfred was born, and within five years there came Bertha, Alice and Louis. The later years of father’s life were embittered by sickness, loss of money and finally a stroke, rendering him helpless. He suffered for 12 years before he passed away in 1902. During that time Francis was an untireing [sic] nurse and faithful companion. She died of a stroke in Philada, 1908.

[handwritten underneath] She was distantly related to Heinrich Heine.]

I found this essay heartwarming, but also sad. Francis was orphaned, married a man with five children who was more than twenty years older than she was, had to put up with his first wife’s parents, raise five stepchildren plus four of her own, and tend to Abraham when he suffered financial and medical problems. What a hard life! But how much of Milton’s essay was true?

When I first wrote about Francis over a year ago, I noted that I’d been able to find very little about her background, so finding this essay was very exciting because it provided many clues about Francis’ background. I’ve placed in bold above the many hints in Milton’s essay about people and places that I thought might reveal more about Francis.

For example, who was Rabbi Krimke who allegedly brought up Francis? Was he just some rabbi from Hanover, or did Milton provide such a specific name because he was a well-known rabbi? It turns out that it was the latter. In Die Rabbiner der Emanzipationszeit in den deutschen, böhmischen und großpolnischen Ländern 1781-1871 (Michael Brocke, Julius Carlebach, Carsten Wilke, Walter de Gruyte, eds. 2010)( p. 549), there was this short biography of Rabbi Isaac Jakob Krimke of Hanover:

Here is a partial translation:

Rabbi Isaak Jakob Krimke, born in Hamburg in 24 June 1824, died in Hannover 20 Nov 1886. From orthodox school, 1857 third foundation rabbi at the Michael Davidschen Foundation School in Hannover, at the same time teacher at the Meyer Michael Foundation School and lecturer at the Jewish Teacher seminary, around 1869 first Foundation Rabbi. at the Michael Davidschen Foundation. Married to Rosa Blogg (died 1889), daughter of the Hebrew scholar Salomon Ephraim B. …. Was buried in the Jewish cemetery An der Strangriede. The tombstone for the foundation rabbi Isaac Jakob Krimke is preserved; it is adorned with a Magen David and also decorated with strong oak leaves….

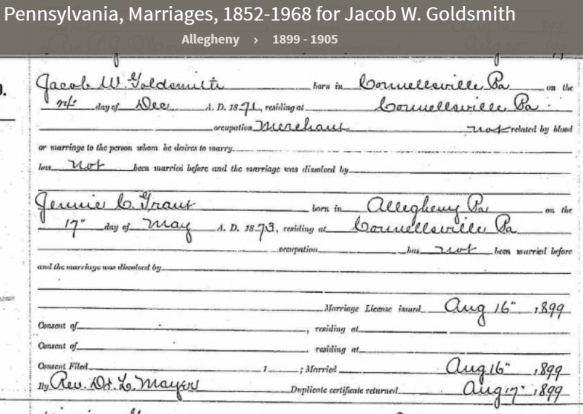

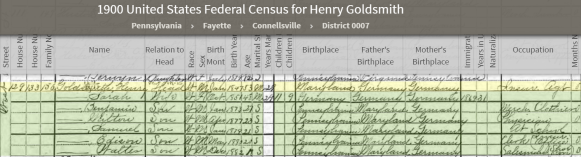

I then fell into a very deep rabbit hole when I tried to track down Louis, Julius, and Rose Spanier, Francis’ uncle, brother, and sister, respectively. I was able to find a Joseph Spanier living with his wife and family in Birmingham, Alabama, on the 1910, 1920 and 1930 census reports. But Joseph Spanier was born in England, according to all three census records. I was skeptical as to whether this was Julius Spanier, the brother of Francis Spanier Goldsmith living in Birmingham, as mentioned in Milton’s essay.

Jos. Spanier and family, 1910, US census, Census Place: Birmingham Ward 2, Jefferson, Alabama; Roll: T624_18; Page: 14A; Enumeration District: 0047; FHL microfilm: 1374031

Ancestry.com. 1910 United States Federal Census

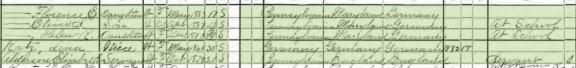

But when I searched further for Julius Spanier, I found this page from the 1861 English census:

Spanier family, 1861 English census, Class: RG 9; Piece: 243; Folio: 61; Page: 28; GSU roll: 542598

Enumeration District: 20, Ancestry.com. 1861 England Census

This certainly appears to be the same man described in Milton’s essay and found on the census records for Birmingham, Alabama, as he was the right age, born in England, and had two sisters, one named Frances, one named Rose. Could it just be coincidence? Also, my Francis was the same age as the Frances on the 1861 English census. This certainly appeared to be the same family as the Spanier family described in Milton’s essay about his stepmother.

What really sealed the deal for me were the names of Joseph Spanier’s children in Birmingham, Alabama. His first child was Adolph; Julius Spanier’s father on the 1861 census was Adolphus. Julius Spanier’s mother was Bertha. Joseph Spanier also had a daughter named Bertha.

And consider the names of the first two children Francis Spanier had with Abraham Goldsmith: a son named Alfred, a daughter named Bertha. It all could not simply be coincidence. I hypothesized that Joseph Spanier was born Julius Spanier in England to Adolphus and Bertha Spanier and that Francis Spanier Goldsmith was his sister.

But then things got murky. Look again at the 1861 English census. It shows that Frances was not born in Germany, but in Boston—in the US. Every American record I had for Francis indicated that she was born in Germany, not the United States. How could I square that with the 1861 English census and the connection to the siblings mentioned in Milton’s essay—Julius and Rose?

And if Frances was born in Boston and living in England in 1861, is it really possible that she did not speak much English when she met Abraham in 1876, as Milton claimed in his essay?

Spanier family, 1861 English census, Class: RG 9; Piece: 243; Folio: 61; Page: 28; GSU roll: 542598

Enumeration District: 20, Ancestry.com. 1861 England Census

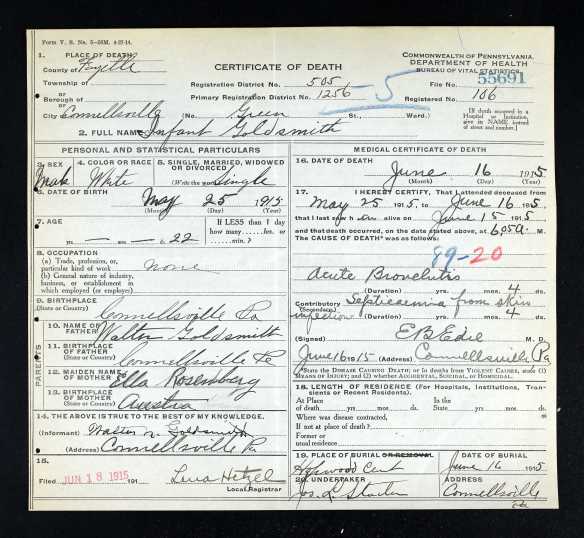

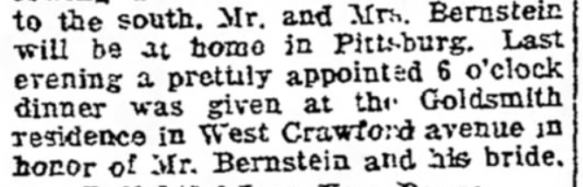

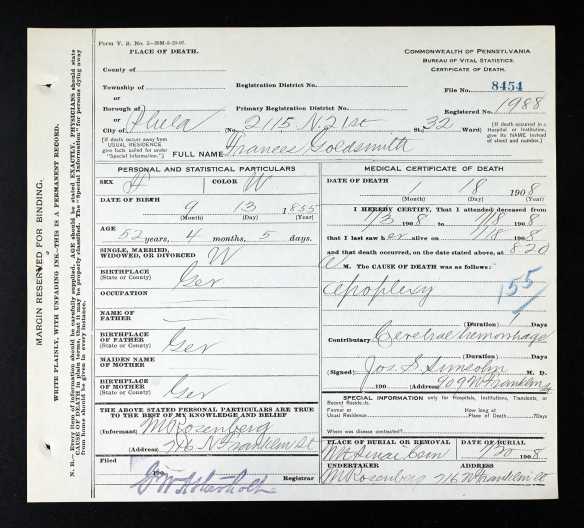

Then I found a birth record for Frances Spanier born in Boston to “Radolph” and Bertha Spanier on September 10, 1854. “Radolph” was clearly a misspelling of Adolph, and this had to be the same Frances Spanier who appeared on the 1861 English census. Francis Spanier Goldsmith had a birth date of September 13, 1855, on her death certificate, so just a year and few days different from this Boston birth record (though the death certificate said she was born in Germany.)

Frances Spanier Goldsmith death certificate

Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission; Pennsylvania, USA; Certificate Number Range: 006001-010000, Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1966

I also found records showing that Francis Spanier Goldsmith’s uncle Louis was living in Boston in the 1850s. It certainly seemed more and more like Francis Spanier Goldsmith was born in Boston, not Germany, as Milton had written and American records reported.

What about the story that she was an orphan and raised by Rabbi Krimke? Francis’ mother Bertha died in England in 1862, when Francis was seven or eight years old, so she was partially orphaned as a child. But her father Adolphus died in England in 1873, so Francis was eighteen or nineteen when he died. But when Francis immigrated to the US in 1876, the ship manifest stated that she was a resident of Germany, not England.

Franziska Spanier, Year: 1876; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: M237, 1820-1897; Microfilm Roll: Roll 403; Line: 1; List Number: 344, Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957

Was Milton’s story just a family myth, or was there some way to reconcile it with these records?

Here is my working hypothesis:

After Bertha Spanier died in 1862, Adolphus was left with five young children. Francis (then seven or eight) and at least some of her siblings were sent to Hanover, Germany, to live with Rabbi Isaak Jakob Krimke, as the family story goes. By the time Francis immigrated to the US fourteen years later, she might have forgotten most of the English she once knew, so she was speaking only German, and the Goldsmith family only knew that she was an orphan who had come from Germany so assumed she was born there, and the family myth grew and stuck.

How ironic would it be if Francis was, like Milton and his siblings, a child whose mother died, leaving her father with five young children? After all, Francis also ended up marrying a man whose first wife died, leaving him with five young children. Francis may have saved her stepchildren from the fate she might have suffered—being taken away from her father after her mother died and sent to live in a foreign country with a stranger, who happened to be a well-known rabbi.

What do you think? Am I missing something here? Where else can I look to try and solve this mystery?

This is Part XII of an ongoing series of posts based on the family album of Milton Goldsmith, generously shared with me by his granddaughter Sue. See Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, Part VI, Part VII , Part VIII, Part IX, Part X and Part XI at the links.