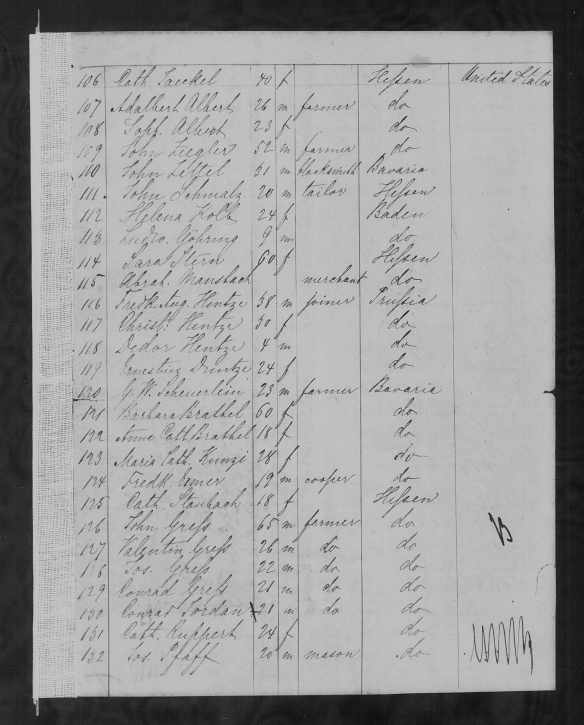

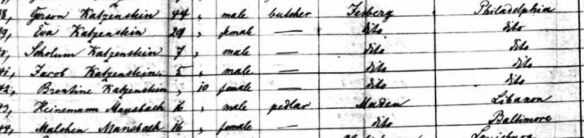

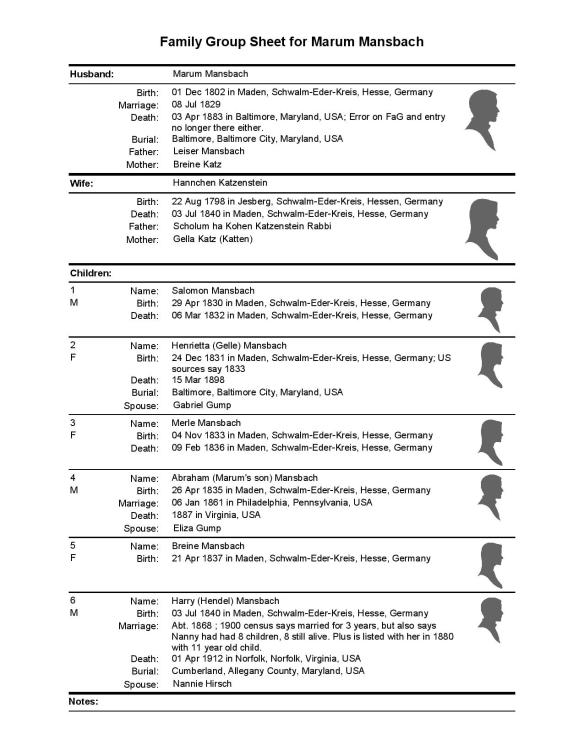

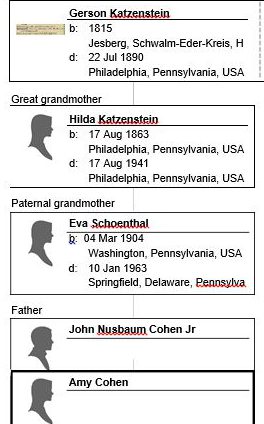

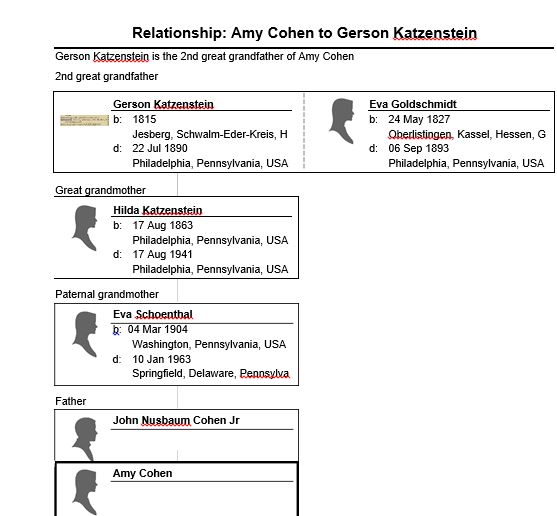

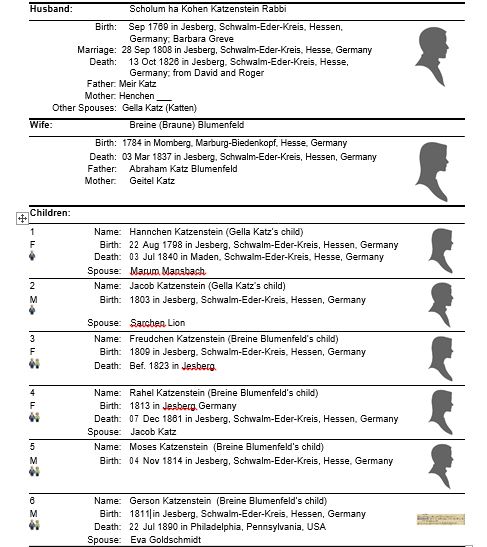

In my prior post about my great-great-grandparents Gerson Katzenstein and Eva Goldschmidt, I was trying to determine whether anyone in either of their families was living in Philadelphia when they immigrated there with their first three children in 1856. The closest possible relative I could find who might have been there first was someone I thought was Gerson’s nephew Abraham Mansbach, son of his half-sister Hannchen Katzenstein and her husband Marum Mansbach of Maden.

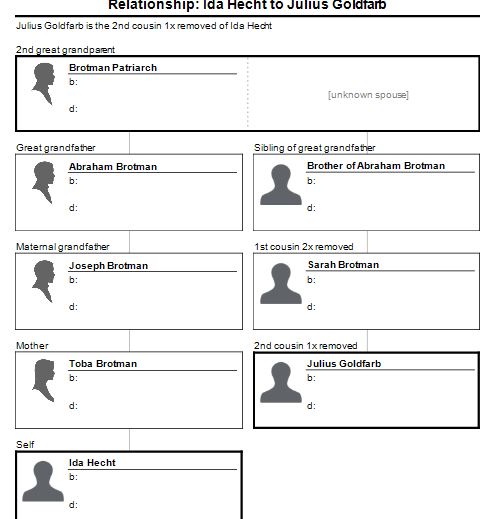

There was an 1852 ship manifest for an Abraham Mansbach, a merchant from Germany, who I thought might be this nephew, but there was no town of origin or age listed on the manifest, so it was hard to know. Also, he had entered the country in Baltimore, not Philadelphia.

Abraham Mansbach 1852 immigration card “Maryland, Baltimore Passenger Lists Index, 1820-1897,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1942-37337-15431-34?cc=2173933 : 17 June 2014), NARA M327, Roll 98, No. M462-M524, 1820-1897 > image 2545 of 3335; citing NARA microfilm publication M327 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

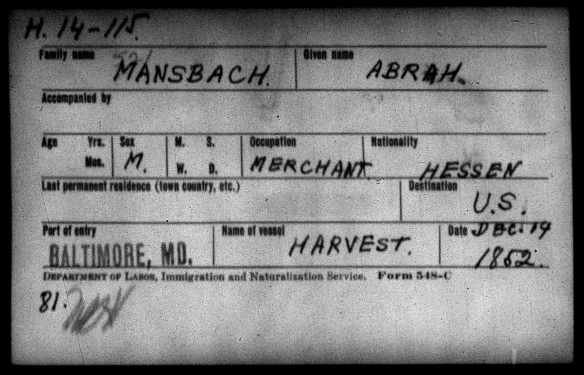

Abraham Mansbach on 1852 passenger list “Maryland, Baltimore Passenger Lists, 1820-1948,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1961-32011-12875-22?cc=2018318 : 25 September 2015), 1820-1891 (NARA M255, M596) > 9 – Jun 2, 1852-Aug 29, 1853 > image 503 of 890; citing NARA microfilm publications M255, M596 and T844 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

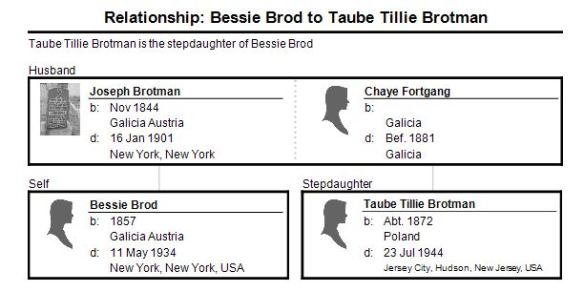

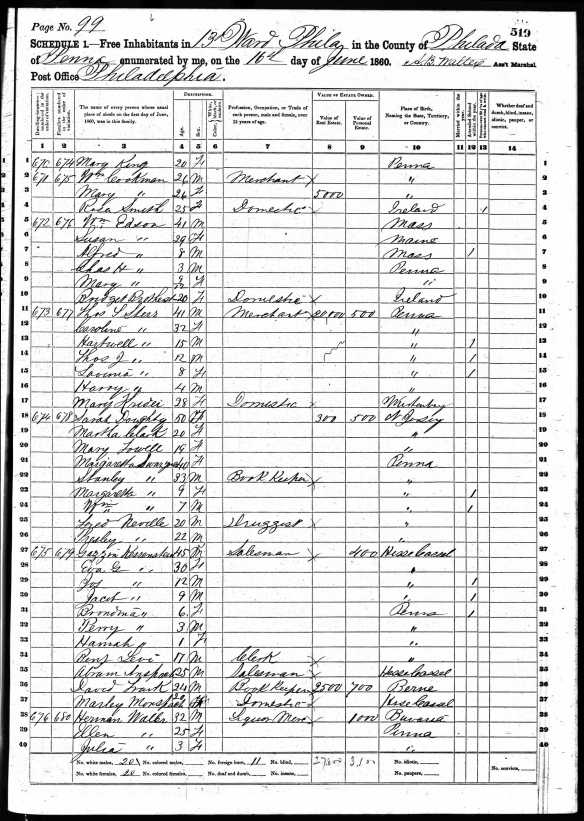

The 1860 census, however, shows that living in the household of Gerson Katzenstein was a 25 year old salesman named Abraham Anspach. Since Gerson’s nephew Abraham was born in 1835, he would have been 25 in 1860. It seemed to me that this was in fact the son of Hannchen Katzenstein and Marum Mansbach, Abraham Mansbach.

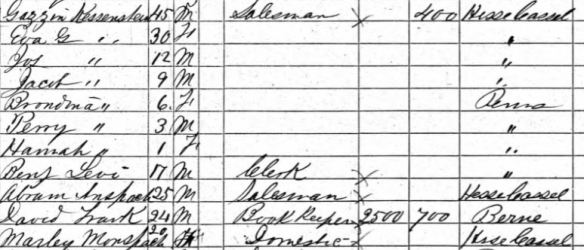

But there was also a 20 year old woman living in the house named Marley Mansbach, and I had at first thought she could be Gerson’s niece and Abraham’s sister Henrietta. I also thought she was likely the same person who was listed on the 1856 ship manifest right below Gerson Katzenstein and his family: a sixteen year old girl named Malchen Mansbach from Maden. But the ages were off from the birth year I had for Henrietta (1833), and the name Henrietta is quite different from Malchen. Most Malchens I’d seen adopted the name Amelia or Amalia; most Henriettas had been Jette in Germany, not Malchen.

Plus there was Heinemann Mansbach, the other sixteen year old who had sailed with Gerson and his family and who’d been heading to “Libanon.” He was not listed on the 1860 census with the Katzenstein family. Who was he, and where was he?

Ship manifest close up

Year: 1856; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: M237, 1820-1897; Microfilm Roll: Roll 164; Line: 1; List Number: 589

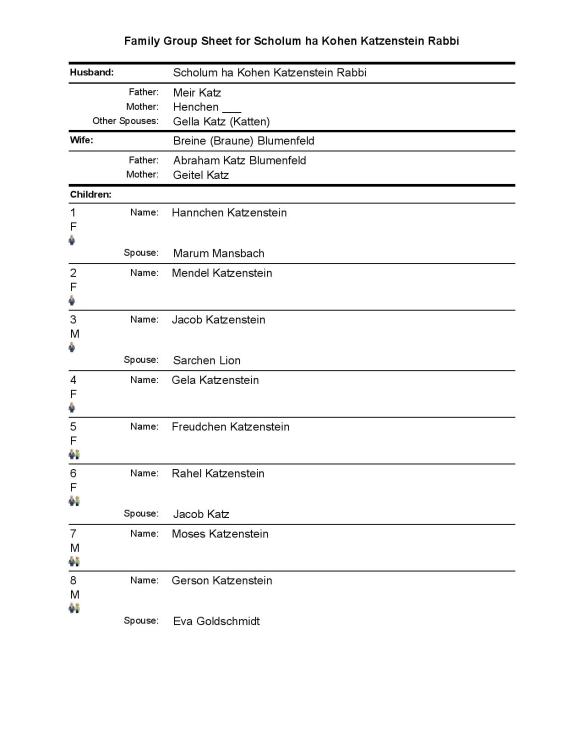

So I consulted with David Baron, and what a Pandora’s box that opened! David worked on this Mansbach puzzle quite extensively and discovered that the Katzenstein family was entwined in multiple ways not only with the Mansbach family, but also the Goldschmidt, Jaffa, and Schoenthal families. Some of this I’d known before, but much of it was new to me and was quite a revelation. There are siblings who married the siblings of their spouses; cousins who married cousins; and so many overlapping relationships that my head was spinning. I won’t describe them all here. I’d lose you all.

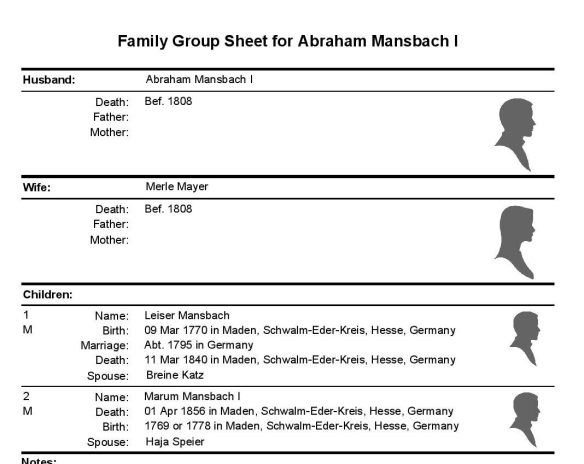

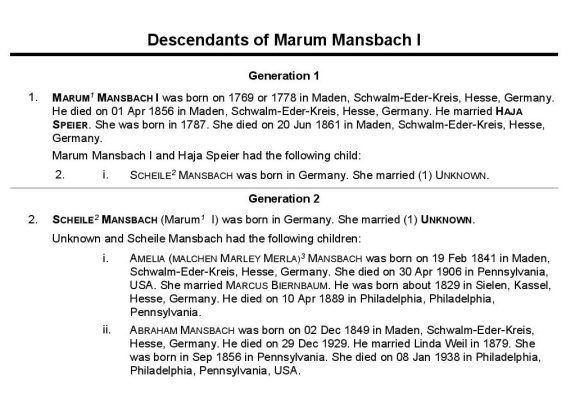

But what David sorted out for me did help answer some of the questions posed above. He pointed me to the work done by Hans-Peter Klein on the Mansbach family from Maden. From Hans-Peter’s work I learned that there were FOUR men from Maden named Abraham Mansbach. The first Abraham Mansbach died sometime before 1808. I will refer to him as Abraham I. He had two sons, Lieser, born in 1770, and Marum, born in either 1769 or 1778 (Marum I).

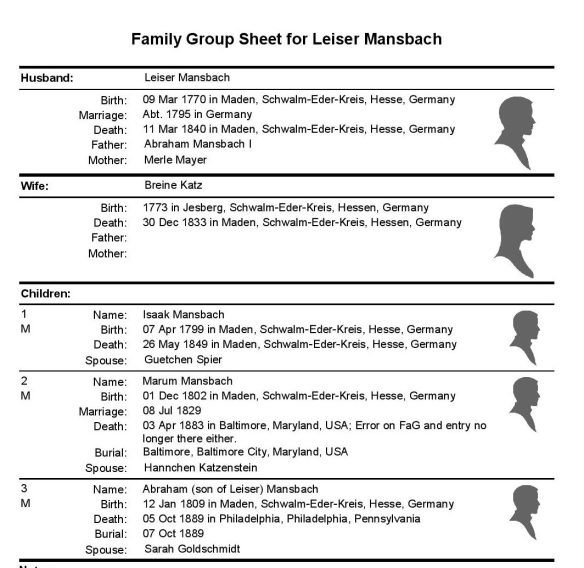

Lieser had three sons: Isaak (1799), Marum II (1802), and Abraham II (1809). So that’s two Abrahams, two Marums. Still with me? Both Abraham I and Abraham II were clearly born too early to have been the Abraham Mansbach on the 1860 census with Gerson.

As a distracting aside, let me mention that Lieser’s son Abraham II married Sarah Goldschmidt, Eva Goldschmidt’s sister, making him the brother-in-law of my great-great-grandparents, Gerson Katzenstein and Eva Goldschmidt. But that’s a story for another day.

Lieser’s son Marum II is the one who married Hannchen Katzenstein, sister of Gerson, and they had Abraham III in 1835. He’s the one I believe is listed with Gerson on the 1860 census; he also appears to be the first member of the Katzenstein line to come to the US.

Finally, Lieser’s brother Marum I had a daughter named Schiele (birth year unknown). Schiele had two children apparently out of wedlock; both took on the surname Mansbach. They were Abraham IV, born in 1849, and Malchen/Merla, born in 1840. Thus, Abraham IV was born fourteen years after Gerson’s nephew, Abraham III, and was far too young to have been the Abraham living with Gerson in 1860 or sailing by himself to America in 1852.

Thus, I feel quite certain that the Abraham Mansbach on the census and on the 1852 ship manifest was Abraham Mansbach III, son of Hannchen Katzenstein and thus Gerson Katzenstein’s nephew.

In addition, David Baron believes, and it seems right to me, that the girl named Malchen Mansbach listed with Gerson and his family on the 1856 ship manifest and the 1860 census was not Henrietta Mansbach, daughter of Marum Mansbach II and Hannchen Katzenstein, but instead the daughter of Schiele Mansbach and sister of Abraham Mansbach IV. Schiele’s daughter Malchen was born in 1840, according to Hans-Peter’s research, and so she would have been sixteen in 1856, as reflected on the manifest, and twenty in 1860, as reflected on the 1860 census. Abraham Mansbach IV, her brother, did not immigrate to the US until 1864.

Having gone down this deep rabbit hole of the extended Mansbach family, I had to pull myself back up and regain my focus. After all, other than the children of Marum Mansbach II and Hannchen Katzenstein, none of these other Mansbachs are genetically connected to me. Their stories are surely important and interesting, but I had to get back to the Katzensteins before I became too distracted.

I now feel fairly confident that the Abraham listed with Gerson in 1860 was in fact his nephew, Abraham Mansbach III, son of Hannchen Katzenstein and Marum Mansbach II, but that Malchen/Marley Mansbach was not their daughter Henrietta and thus not Gerson’s niece. But I still had questions about Hannchen and Marum’s two other children, Heinemann/Harry and Henrietta. In 1860, where was Heinemann Mansbach, the third child of Hanne and Marum, the one who had sailed with Gerson in 1856 and whose destination was apparently Lebanon, PA? And when, if at all, did Henrietta arrive in the US?

More on that in my next few posts.

![By Mathew Brady [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/512px-mark_twain_brady-handy_photo_portrait_feb_7_1871_cropped.jpg?w=394&h=614)