As of 1930, only six of Jacob Goldsmith’s fourteen children were still living: Annie, Celia, Frank, Rebecca, Florence, and Gertrude. As seen in my prior posts, Eva died in 1928. In addition, I have written about the deaths of Gertrude in 1937 and Rebecca in 1940. There remain therefore just four siblings to discuss, and by 1945, they were all deceased.

Annie and Celia, the two oldest remaining siblings, both died in 1933. Celia, who’d been living with her sister Florence and her family in 1930, died on January 15, 1933, in Denver, and was buried in Philadelphia on January 18, 1933. She was 73 years old. Celia never married and has no living descendants.1

Her sister Annie died four months later, on May 29, 1933, in San Francisco.2 She was 77 and was survived by her three children, Josephine, Harry, and Fanny. Sadly, Harry did not outlive his mother by much more than a year. He died at 53 on August 4, 1934, in San Francisco.3 He was survived by his wife Rose, who died in 1969, and his two sisters, Josephine and Fanny. But Josephine also was not destined for a long life. She died less than three years after her brother Harry on April 23, 1937; she was 59. Like their father Augustus who’d died when he was fifty, Josephine and Harry were not blessed with longevity.

Find A Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com : accessed 05 March 2019), memorial page for Fannie Mendelsohn Frank (unknown–1 Sep 1974), Find A Grave Memorial no. 100371723, citing Home of Peace Cemetery and Emanu-El Mausoleum, Colma, San Mateo County, California, USA ; Maintained by Diane Reich (contributor 40197331) .

Of Augustus and Annie’s children, only Fanny lived a good long life. She was 93 when she died on September 1, 1974.4 According to her death notice in the San Francisco Chronicle, she had been a dealer in Oriental art objects.5 Like Josephine, Fanny had never married and had no children, nor did their brother Harry. Thus, there are no living descendants of Annie Goldsmith Frank.

Find A Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com : accessed 05 March 2019), memorial page for Fannie Mendelsohn Frank (unknown–1 Sep 1974), Find A Grave Memorial no. 100371723, citing Home of Peace Cemetery and Emanu-El Mausoleum, Colma, San Mateo County, California, USA ; Maintained by Diane Reich (contributor 40197331) .

The third remaining child of Jacob Goldsmith was Florence Goldsmith Emanuel. In 1930, Florence was living with her husband Jerry Emanuel in Denver as well as their nephew Bernard, the son of Gertrude Goldsmith and Jacob Emanuel, and Florence’s sister Celia. Jerry was working as a clerk in a wholesale tobacco business. In 1940, they were still living in Denver, now with Jerry’s sister Grace in their home, and Jerry was working as a salesman for a wholesale liquor business.6

Emanuel family, 1930 US census, Census Place: Denver, Denver, Colorado; Page: 2A; Enumeration District: 0137; FHL microfilm: 2339973

Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census

Florence Goldsmith Emanuel died on August 4, 1942, at the age of 73. Her husband Jerry survived her by another seventeen years. He died on June 16, 1959, and is buried with Florence in Denver. He was 89. Florence and Jerry did not have children, so like so many of Florence’s siblings, there are no living descendants.7

That brings me to the last remaining child of Jacob Goldsmith and Fannie Silverman, their son Frank. In 1930, Frank and his wife Barbara were living in Atlantic City, and Frank was retired.8 On July 25, 1937, Barbara died in Philadelphia; she was 67. Like Frank’s parents and many of his siblings, she was buried at Mt Sinai cemetery in Philadelphia; in fact, she was buried in the same lot as Celia and Rachel Goldsmith and one lot over from her in-laws Jacob and Fannie Goldsmith.9

I mention this because for the longest time I was having no luck finding out when or where Frank Goldsmith died or was buried. In 1940, he was living as a widower in the Albemarle Hotel in Atlantic City, and the 1941 Atlantic City directory lists Frank as a resident.9 But after that he disappeared. I couldn’t find any obituaries or death records, but what really mystified me was that there was no record of his burial with his wife Barbara and his other family members at Mt Sinai cemetery.

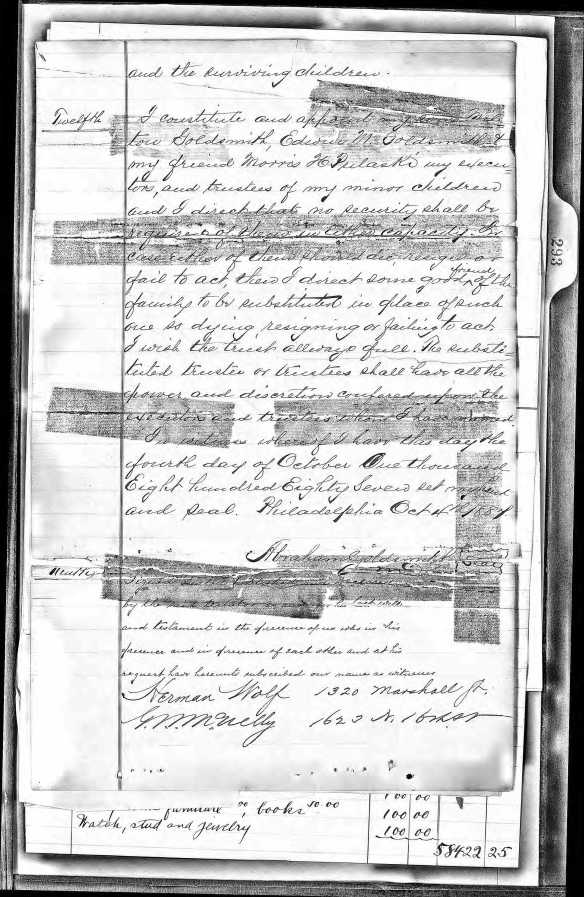

I contacted Mt Sinai and learned that the plot that had been reserved for Frank is still unused. Barbara is buried with Frank’s sisters Celia and Rachel and one lot over from Frank’s parents. But Frank is not there. Here are two of the Mt Sinai burial records showing that Barbara and Celia are buried right near each other in lots owned by Frank.

Historical Society of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records, Mt· Sinai Cemetery, Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Church and Town Records, 1669-2013

I also hired a researcher to search the New Jersey death certificates in Trenton (since they are not available online). She came up empty. So what had happened to Frank?

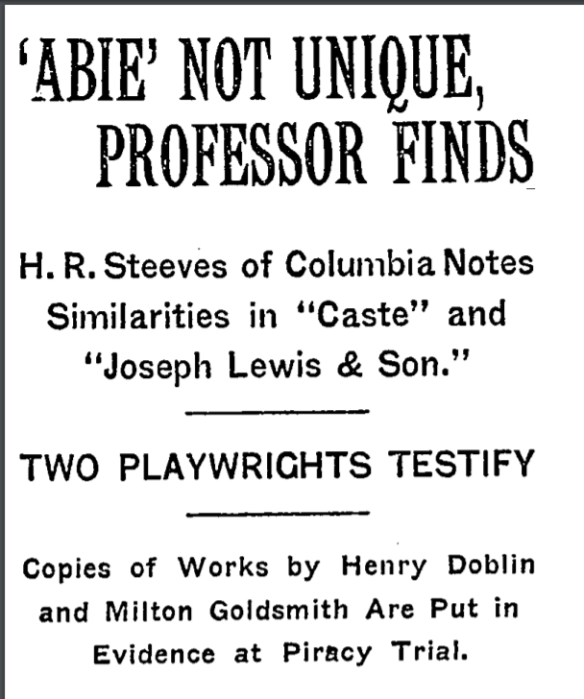

Well, once again Tracing the Tribe, the Jewish genealogy Facebook group, came to the rescue. I posted a question there and received many responses, most of them suggestions for things I’d already done. But one member, Katherine Dailey Block, found a 1920 newspaper article that mentioned Frank that I had never seen:

That raised the possibility that Frank might have spent time in Florida more than this one time. I had made the mistake of assuming that, having lived his whole life in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, he must have died in one of those two states. Now I broadened the search to Florida. (Doing a fifty-state search was not helpful since the name Frank Goldsmith is quite common, and I had no way to figure out whether any of them was my Frank.) And this result came up:

Florida Death Index, 1877-1998,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VV91-P84 : 25 December 2014), Frank F. Goldsmith, 1945; from “Florida Death Index, 1877-1998,” index, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com : 2004); citing vol. 1148, certificate number 9912, Florida Department of Health, Office of Vital Records, Jacksonville.

A Frank F. Goldsmith had died in Tampa, Florida in 1945. Could this be my Frank? Tampa is on the opposite coast from Jacksonville as well as much further south. That made me doubt whether this was the same Frank F. Goldsmith. But then I found this record from the 1945 Florida census; notice the second to last entry on the page:

Census Year: 1945, Locality: Precinct 2, County: Hillsborough, Page: 43, Line: 32

Archive Series #: S1371, Roll 20, Frank F. Goldsmith 65

Ancestry.com. Florida, State Census, 1867-1945

There was Frank F. Goldsmith, and when I saw that he was born in Pennsylvania, I was delighted, figuring that this could be my Frank. On the other hand, the census reported that this Frank was 65 years old in 1945 whereas my Frank would have been 82. But it seemed worth ordering a copy of the death certificate from the Florida vital records office to see if it contained information that would either confirm or disprove my hope that this was my cousin Frank.

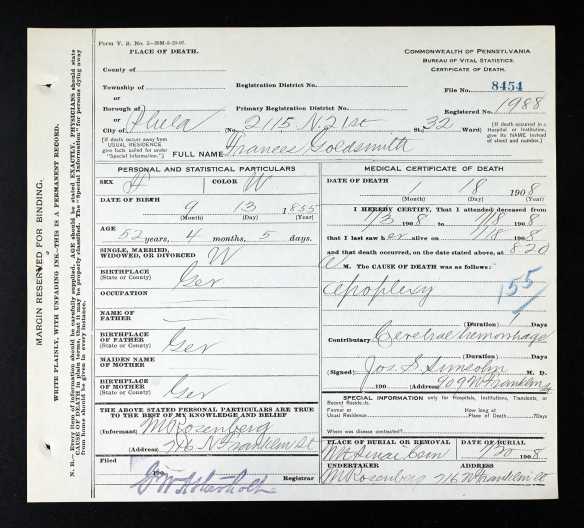

Unfortunately, here is the death certificate:

As you can see, it has no information about this Frank F. Goldsmith’s wife, parents, birth place, occupation, or much of anything that would help me tie him to my Frank F. Goldsmith. In fact, the age and birth date on the certificate are inconsistent with my Frank Goldsmith, who was born in June 1863, according to the 1900 census, not June of 1878.

Despite these blanks and inconsistencies, my hunch is that this is my Frank. Why? Both Franks have a birth date in June. And on later census records, Frank’s estimated birth year based on his reported age moved later than 1863—1868 in 1910, 1876 in 1920, and 1870 in 1930 and 1940. He seemed to be getting younger as time went on. Maybe by 1945, he was giving a birth year of 1878. And by 1945 there was no one left to inform the hospital of his family’s names or his birth date or age so perhaps whoever completed the death certificate (looks like someone from the funeral home) was just guessing at his age and birth date.

In addition, there is no other Frank F. Goldsmith who fits the parameters of the Frank on the death certificate. Finally, this Frank was to be buried in the “Jew cemetery,” so we know that he was Jewish.

So what do you think? Is this enough to tie the Frank F. Goldsmith who died in Florida to my Frank F. Goldsmith? I know these are thin reeds upon which to make a case, but I think they may have to be enough.

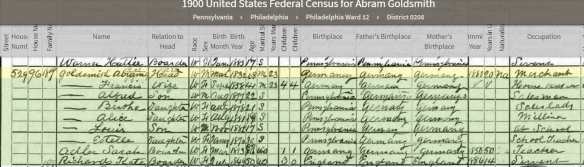

In any event, like his sisters Rachel, Celia, Annie, Emma, Eva and Florence, and his brother Felix, Frank Goldsmith has no living descendants. In fact, it is quite remarkable how few living descendants Jacob Goldsmith and Fannie Silverman have, considering that they had had fourteen children. Five of those fourteen children did not have children of their own: Emma, Rachel, Celia, Frank, and Florence. Four of Jacob and Fannie’s children had no grandchildren: Annie had three children, but none of them had children. Eva had one son, Sidney, who did not have any children, and the same was true of Gertrude’s son Bernard and Felix’s two children Ethel and Clarence. From fourteen children, Jacob and Fannie had twenty grandchildren and only twelve great-grandchildren, and a number of those great-grandchildren also did not have children. From my count, there were only ten great-great-grandchildren. With each generation, instead of growing, the family became smaller.

But that is not the legacy of Jacob and Fannie Goldsmith. Rather, theirs is the remarkable story of two young German immigrants settling in western Pennsylvania and then Philadelphia, raising fourteen children who eventually spanned the continent. From all appearances, many of those fourteen children stayed close, both geographically and presumably emotionally. Many of them lived together, especially the daughters who spent years in Denver together. Like so many first-generation Americans, these fourteen children provided evidence to their parents that the risks they took leaving their home country behind and crossing the ocean were worthwhile. Yes, there was plenty of heartbreak along the way, but overall Jacob, Fannie, and their fourteen children lived comfortably and free from oppression.

- Historical Society of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records, Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Church and Town Records, 1669-2013 ↩

- Ancestry.com. California, Death Index, 1905-1939 ↩

- Ancestry.com. California, Death Index, 1905-1939 ↩

- Number: 562-66-4663; Issue State: California; Issue Date: 1962, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014 ↩

- San Francisco Chronicle, September 4, 1974, p. 35 ↩

- Florence Emanuel, 1940 US census, Census Place: Denver, Denver, Colorado; Roll: m-t0627-00490; Page: 9A; Enumeration District: 16-221B, Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census ↩

- JewishGen, comp. JewishGen Online Worldwide Burial Registry (JOWBR) ↩

- Frank Goldsmith, 1930 US census, Census Place: Atlantic City, Atlantic, New Jersey; Page: 19B; Enumeration District: 0011; FHL microfilm: 2341043, Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census ↩

- Historical Society of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records, Mt· Sinai Cemetery, Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Church and Town Records, 1669-2013 ↩ ↩