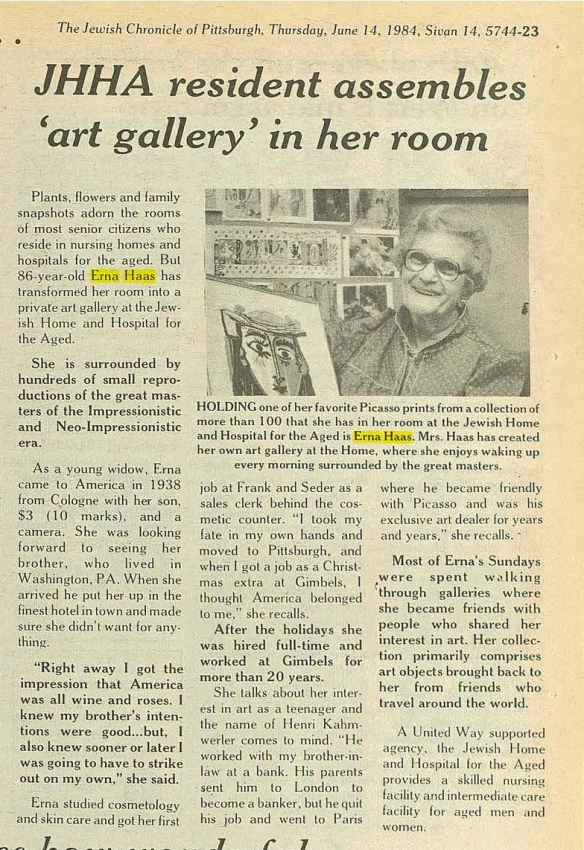

As I move towards closure on my Schoenthal family history, this post has been the hardest one to write. It is a tragic chapter in that history.

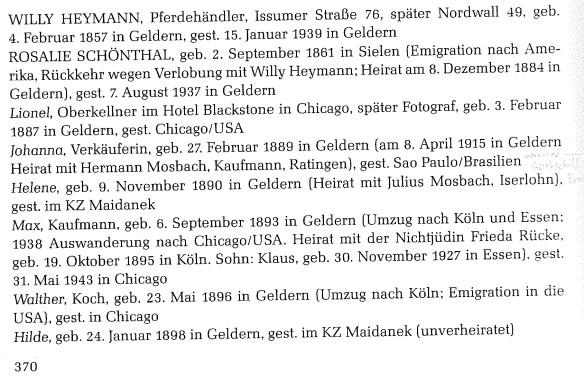

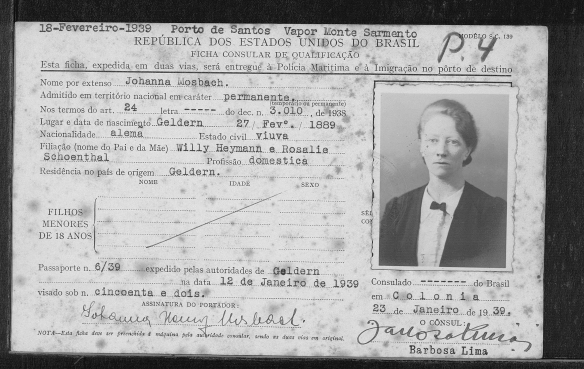

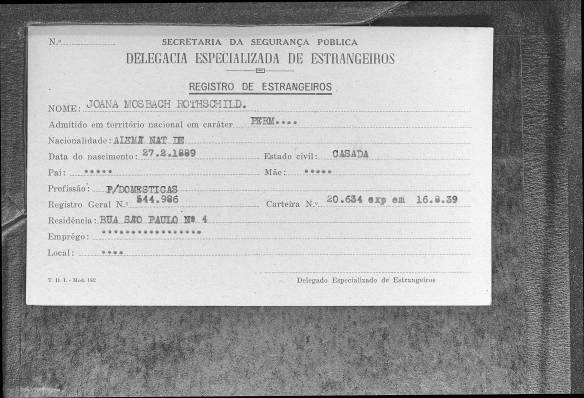

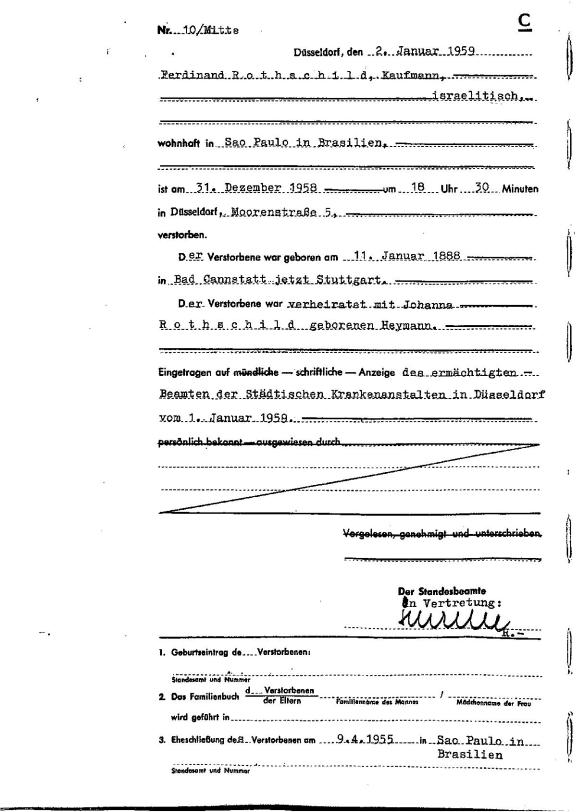

As I’ve already written, four of the six children of my great-great-aunt Rosalie Schoenthal and her husband Willy Heymann left Germany before they could be killed by the Nazis. The three sons went to Chicago, and the oldest daughter Johanna went to Sao Paulo. They all survived. The other two daughters were not so lucky.

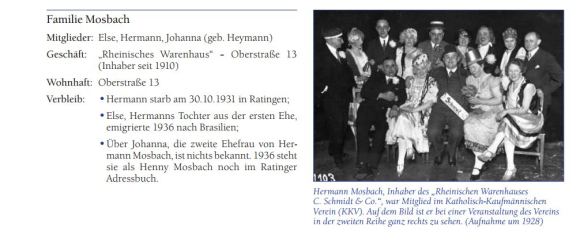

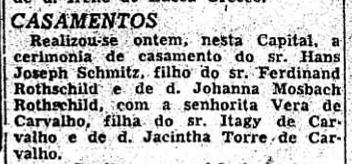

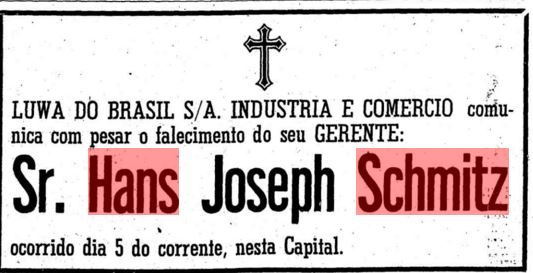

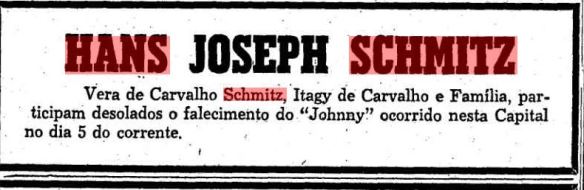

The second oldest daughter, Helene, was born in Geldern in November 9, 1890, a year after Johanna. She married Julius Mosbach, who was the younger brother of Johanna’s first husband, Hermann Mosbach. After marrying, Julius and Helene were living in Iserlohn, a town about 80 miles east of Geldern. According to an article written in 2000 by the archivist of Iserlohn, Gotz Bettge, Julius and Helene Mosbach owned a fruit and vegetable business in the town square in Iserlohn. They had two daughters: Liesel, who was born March 8, 1921, and Gretel, born October 26, 1926.

![Iserlohn By No machine-readable author provided. Asio otus assumed (based on copyright claims). [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/iserlohn-muehlentor1-asio.jpg?w=584)

Iserlohn

By No machine-readable author provided. Asio otus assumed (based on copyright claims). [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

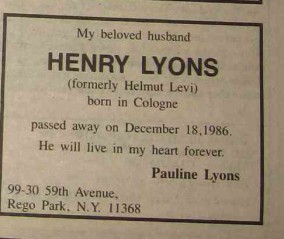

On December 18, 1939, Liesel married Ernst Georg Lion. From the incredibly moving autobiography written by Ernst Lion entitled The Fountain at the Crossroads and available online here, I was able to learn a great deal about his life and also about the lives of Julius, Helene, and their daughters. All the information and quotes below are from his book unless otherwise indicated. (Special thanks to Dorothee Lottmann-Kaeseler for sending me some of the additional links and information.)

Ernst was born December 15, 1915, in Brambauer, the son of Leo Lion and Bertha Weinberg Lion. When Ernst was a very young child, his father Leo was badly injured while serving in the German army during World War I. Leo Lion considered himself a German patriot.

Ernst grew up as the only Jewish child in Brambauer during the hard years of the Weimar Republic, but his childhood was overall quite happy. Then Hitler came to power, and his life was forever changed. The Nazis tried to impose a boycott on his father’s business by having a Gestapo member stand in the doorway and take photographs of those who patronized his store. Ernst’s father insisted that the man leave, even threatening to beat him up. He did not think the Nazis would be in power for very long. But then when the Nuremberg laws were enacted in 1935, the family had to sell their home and their store for less than their value and move to Dortmund.

Many members of the extended Lion/Weinberg family left Germany around that time, but Ernst had difficulty getting the necessary visas and permits to go elsewhere even though he had an affidavit of support from a cousin in New York. Then on November 9, 1938, Ernst was one of thousands of German Jews who were arrested and sent to Buchenwald in the aftermath of Kristallnacht. In his autobiography he described in graphic detail his experiences there. It’s horrifying.

Ernst was released a few weeks later and told to leave the country within three weeks. All the Jewish businesses were now closed, and he was forced to work on street repairs while waiting to emigrate.

![Buchenwald Watch Tower undesarchiv, Bild 183-1983-0825-303 / CC-BY-SA 3.0 [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/buchenwald.jpg?w=584)

Buchenwald Watch Tower

undesarchiv, Bild 183-1983-0825-303 / CC-BY-SA 3.0 [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

But then he met Liesel Mosbach in Iserlohn. He was introduced by his Aunt Selma who lived there, and they immediately took a liking for each other. At that time Liesel’s family was living in the apartment above their former business, which had been confiscated by the Nazis. Julius Mosbach had suffered a nervous breakdown as a result of the harassment by the Nazis and the loss of his business, and he was doing very poorly.

Ernst moved to Iserlohn in 1939, where his aunt was able to help him get a job at a metal working company owned by a family that was unsympathetic to the Nazi government and its policies; the owners even provided Ernst with extra food to supplement the very restrictive allotments allowed to the Jews by the Nazis.

When the Nazis then imposed travel restrictions and required Jews to wear the yellow Star of David, Ernst was no longer able to get to Dortmund to visit his parents. His mother died shortly thereafter, having given up on life, according to his father; Ernst was not even allowed to go to her funeral.

Yellow badge Star of David called “Judenstern”. Part of the exhibition in the Jewish Museum Westphalia, Dorsten, Germany. The wording is the German word for Jew (Jude), written in mock-Hebrew script. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

On December 18, 1939, Ernst and Liesel were married. As Ernst wrote, although they had no idea what the future would bring, “The secret of maintaining one’s sanity under those conditions is to live as normal a life as one can.” (p. 18) Unfortunately, that became more and more difficult to do. Conditions for the Jews continued to worsen, and there was less food available. People were beginning to hear about Jews being arrested and sent away.

In January, 1941, Julius Masbach was admitted to a mental hospital and died shortly thereafter. Ernst wrote (p.15):

We soon discovered that we should have opposed the doctor’s decision [to hospitalize Julius], for the Nazis had decided that all institutionalized, so-called “insane” persons no longer had the right to live and had become a burden to society. They were led into sheds equipped with gasoline engines, which were installed in reverse fashion: the exhaust escaped to the inside of the building. After they were asphyxiated, the bodies were burned and the ashes delivered to the surviving families. No one realized that this activity was the rehearsal for later mass destruction of humans.

On April 28, 1942, Helene Heymann Mosbach, my grandmother’s first cousin, and her daughter Gretel, just sixteen years old, were arrested and sent to Zamosc, near Lublin, Poland. They were never heard from again. Ernst’s father Leo Lion was also arrested around this time, and Ernst never heard from him again either.

To add to this heartbreaking account, Helene’s sister Hilda, the youngest of the six children of Rosalie Schoenthal and Willy Heymann, was also killed by the Nazis. Although she is not mentioned in Ernst Lion’s autobiography or on the website memorializing the Mosbach family, according to Yad Vashem, Hilda also had been living in Iserlohn before being sent Zamosc where her sister Helene and niece Gretel had been deported. I assume that Hilda had moved to Iserlohn to live with her sister Helene after both her mother Rosalie (1937) and her father Willy (1939) had died.

I had not heard of Zamosc before, and my friend Dorothee Lottmann-Kaeseler sent me this link that reveals the absolutely horrifying story of this place. There are no records of what happened specifically to Helene, Gretel, and Hilda, but it is possible that they were killed in Zamosc itself or deported to the death camp at Majdanek or Belzec or Sobibor, where they were killed.

![Crematoria at Majdanek death camp near Lublin, Poland Deutsche Fotothek [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/majdanek-crematoria.jpg?w=584&h=368)

Crematoria at Majdanek death camp near Lublin, Poland

Deutsche Fotothek [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

On February 26, 1943, Ernst and Liesel received orders to report to a school in Dortmund with just one suitcase each. There were about a thousand people at the school that night, and everyone was forced to sleep on the floor. Ernst wrote, “They took our wedding bands and watches, telling us that we would not need them where we were going.” (p. 19)

The next morning they were put on a freight train (pp.19-20):

I found myself inside such a freight car among a hundred men, women and children. The doors were locked; there were no windows to look through. This precaution would keep us from recognizing our route or destination. A few buckets for relief, no food or water. This should be a short ride, I mused.

… Liesel was shoved on this train with me. At least we were together. Just twenty-three, she was a thin, wiry lady, strong and energetic. Her dark eyes expressed the will to endure. I was twenty-four. Where was our future?

Although they were told they were being taken to a safe place for resettlement, Ernst was skeptical, as he had good reason to be. They were being taken to Auschwitz-Birkenau. When they arrived, they were told to leave their suitcases on the train; then they stepped onto the platform surrounded by SS guards and prisoners in striped uniforms who were helping with the unloading.

Then the men and women were separated.

Ernst wrote, “All the women were led away. My wife looked at me for one last time before she disappeared. It was dark now, and I saw her walk away like a shadow.”

He never saw her again. Liesel Mosbach Lion, my father’s second cousin, was murdered at Auschwitz.

I consider the entire family to be victims of the Holocaust: Rosalie, Willy, Helene, Julius, Liesel, Gretel, and Hilda as well as Leo and Bertha Lion.

Ernst Lion, however, survived. The story of how he survived is remarkable. It’s a tale of incredible courage, strength, persistence, and luck. It’s also a horrifying, nightmarish account of how cruel human beings can be to one another. You should all read it. I cannot do it justice in a blog post. You must read it. Again, you can find it here. Please read it.

I am so grateful that Ernst, Liesel’s husband, survived and recorded his story and their story for us all to read. We must never forget.

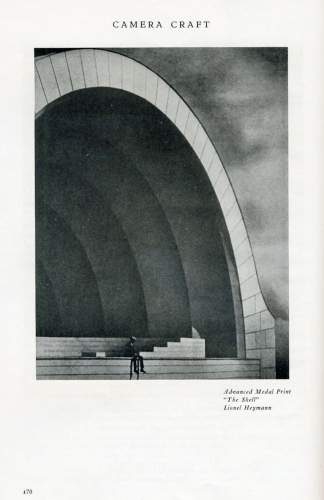

![Ancestry.com. Historical Newspapers, Birth, Marriage, & Death Announcements, 1851-2003 [database on-line].](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/lionel-heymann-death-notice.jpg?w=584&h=300)

![Ancestry.com. Historical Newspapers, Birth, Marriage, & Death Announcements, 1851-2003 [database on-line].](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/lionel-heymann-obit-clipped.jpg?w=584)

![By Dornicke (Own work) [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/sinagoga_beth_el_sc3a3o_paulo_1.jpg?w=584&h=438)

![Photograph by Lionel Heymann of Robert Maynard Hutchins, University of Chicago president (1929-1945) and chancellor (1945-1951), with team members of the Manhattan Project, the program established by the United States government to build the atomic bomb. Standing, from left: Mr. Hutchins, Walter H. Zinn, and Sumner Pike; seated: Farrington Daniels, and Enrico Fermi. University of Chicago Photographic Archive, [apf digital item number, e.g., apf12345], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. accessed at http://photoarchive.lib.uchicago.edu/db.xqy?one=apf1-05063.xml](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/lionel-heymann-photograph-of-men-on-manhattan-project.jpg?w=584&h=735)

![Lionel Heymann 1911 UK census Ancestry.com. 1911 England Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: Census Returns of England and Wales, 1911. Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the UK (TNA), 1911. Data imaged from the National Archives, London, England.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/lionel-heymann-1911-uk-census.jpg?w=584&h=343)

![Lionel Heymann 1912 passenger manifest Ancestry.com. UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012. Original data: Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Outwards Passenger Lists. BT27. Records of the Commercial, Companies, Labour, Railways and Statistics Departments. Records of the Board of Trade and of successor and related bodies. The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, England.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/lionel-heymann-1912-passenger-manifest.jpg?w=584&h=757)

![Lionel Heymann 1924 passenger manifest Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/lionel-heymann-1924-passenger-manifest.jpg?w=584&h=488)

![Ancestry.com. U.S. Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791-1992 (Indexed in World Archives Project) [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/lionel-heymann-1933-naturalization-e1458863553259.jpg?w=584&h=449)

![Lionel Heymann World War II draft registration Ancestry.com. U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: United States, Selective Service System. Selective Service Registration Cards, World War II: Fourth Registration.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/lionel-heymann-ww2-draft-reg.jpg?w=584&h=368)

![Max Heymann World War II draft registration Ancestry.com. U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: United States, Selective Service System. Selective Service Registration Cards, World War II: Fourth Registration](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/max-heymann-ww2-draft-registration.jpg?w=584&h=368)

![Walter Heymann World War II draft registration Ancestry.com. U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: United States, Selective Service System. Selective Service Registration Cards, World War II: Fourth Registrati](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/walter-heymann-world-war-2-draft-reg.jpg?w=584&h=370)

![Heinrich Stern death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/heinrich-stern-death-certificate.jpg?w=584&h=440)

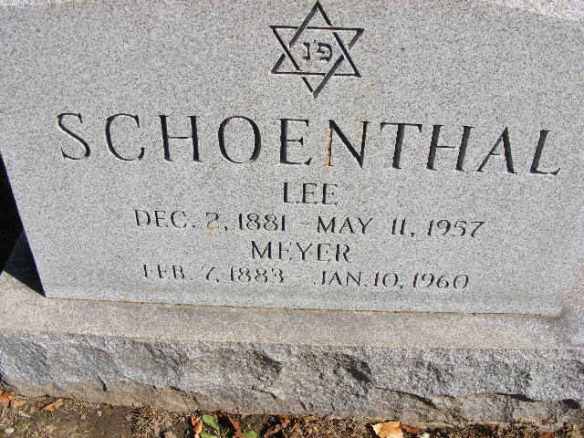

![Lee Schoenthal death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/lee-schoenthal-death-certificate-1957.jpg?w=584&h=435)

![Meyer N Schoenthal death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/meyer-n-schoenthal-death-cert-1960.jpg?w=584&h=436)

![Werner Haas death certificate Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1963. Series 11.90 (1,905 cartons). Records of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Record Group 11. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/werner-haas-death-certificate.jpg?w=584&h=437)

![Railroad tracks to Gurs By Jean Michel Etchecolonea (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/800px-gurs_voie-ferree.jpg?w=584&h=438)

![Cemetery for those who died at Gurs By Jean Michel Etchecolonea (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://brotmanblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/1024px-gurs_tombes-3.jpg?w=584&h=438)