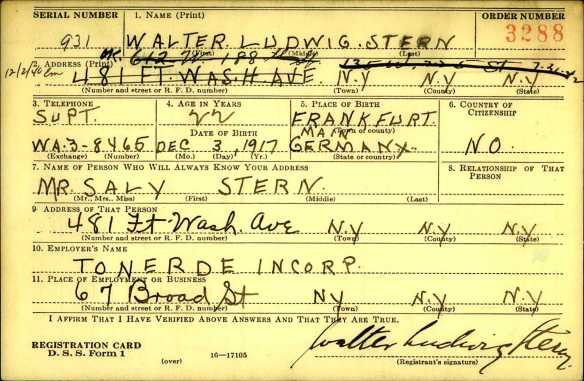

In my last post, we saw that Helmina Goldschmidt Rapp and her daughter Alice Rapp Stern, son-in-law Saly Stern, and their daughters Elizabeth and Grete had first escaped to England from Nazi Germany, with Alice, Saly, and Elizabeth later immigrating to the US where their son Walter had already settled. Today’s post is about Helmina Goldschmidt Rapp’s son Arthur Rapp and his family.

Arthur and his wife Alice and their sons Helmut and Gunther also were in England by 1939. Arthur reported on the 1939 England and Wales Register that he was a retired telephone salesman. (The two black lines are presumably for Helmut/Harold and Gunther/Gordon, who must still have been living when the document was scanned.)

Arthur and his wife Alice and their sons Helmut and Gunther also were in England by 1939. Arthur reported on the 1939 England and Wales Register that he was a retired telephone salesman. (The two black lines are presumably for Helmut/Harold and Gunther/Gordon, who must still have been living when the document was scanned.)

Arthur Rapp and Family,The National Archives; Kew, London, England; 1939 Register; Reference: RG 101/6823F, Enumeration District: WFQC, Ancestry.com. 1939 England and Wales Register

But like his sister Alice, Arthur did not stay in England. First, in 1940, he and his family immigrated to Brazil. I love having these photographs of Arthur and his family. Gunther is particularly adorable. But then I remember that these people had to leave their home in Frankfurt and then uproot themselves again to go from England to Brazil.

Arthur Rapp, Digital GS Number: 004816338, Ancestry.com. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Immigration Cards, 1900-1965

Alice Kahn Rapp, Digital GS Number: 004911328, Ancestry.com. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Immigration Cards, 1900-1965

Helmut Rapp, Digital GS Number: 004871140, Ancestry.com. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Immigration Cards, 1900-1965

Gunther Rapp, Digital GS Number: 004911328, Ancestry.com. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Immigration Cards, 1900-1965

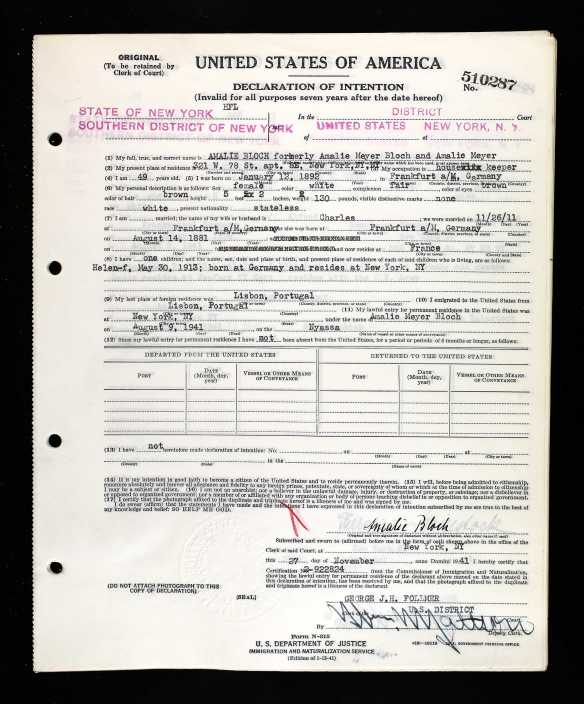

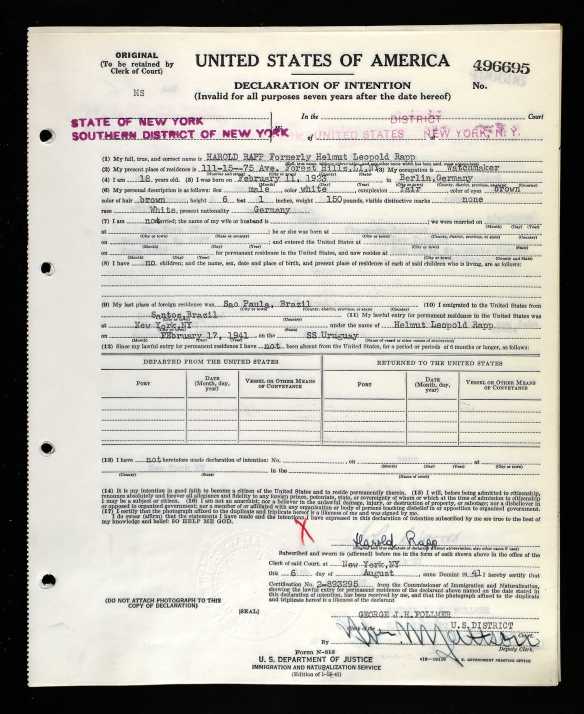

But a year later on February 27, 1941, they uprooted themselves again and left Brazil for New York where they settled in Forest Hills, New York, as seen on Arthur’s declaration of intention to become a US citizen.

Arthur Rapp, declaration of intention, The National Archives at Philadelphia; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; NAI Title: Declarations of Intention for Citizenship, 1/19/1842 – 10/29/1959; NAI Number: 4713410; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: 21, Description: (Roll 626) Declarations of Intention for Citizenship, 1842-1959 (No 496501-497400), Ancestry.com. New York, State and Federal Naturalization Records, 1794-1943

Arthur reported on his declaration of intention that he was unemployed, but his son Helmut, now using the name Harold, reported on his declaration that he was a watchmaker.

Harold (Helmut) Rapp, declaration of intention, The National Archives at Philadelphia; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; NAI Title: Declarations of Intention for Citizenship, 1/19/1842 – 10/29/1959; NAI Number: 4713410; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: 21, Description: (Roll 626) Declarations of Intention for Citizenship, 1842-1959 (No 496501-497400), Ancestry.com. New York, State and Federal Naturalization Records, 1794-1943

Arthur and Alice’s younger son Gunther, who became Gordon, was sixteen when they immigrated; on his World War II draft registration in 1943, he was living in Monmouth, New Jersey, working for Modern Farms.

Gordon (Gunther) Rapp, World War II draft registration, The National Archives in St. Louis, Missouri; St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards for New Jersey, 10/16/1940-03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147; Box: 539

Ancestry.com. U.S. WWII Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947

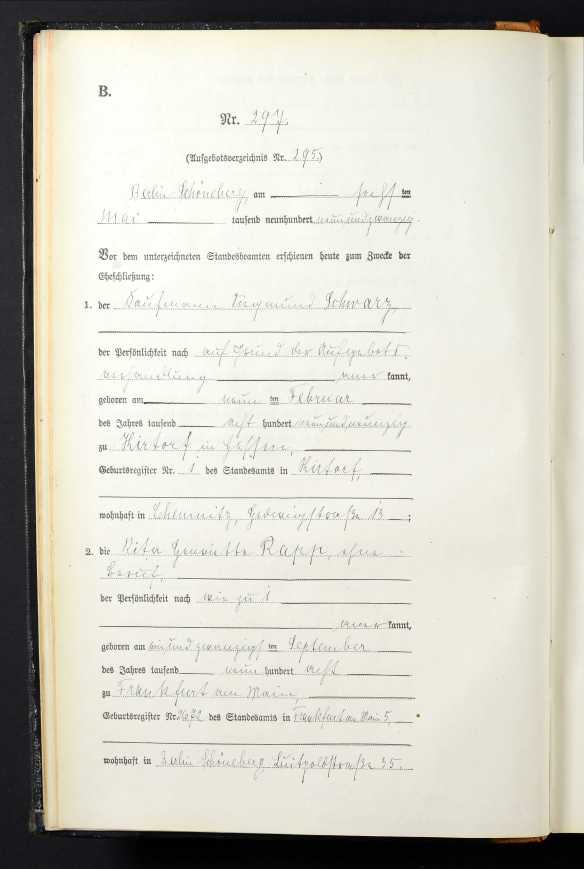

Arthur’s daughter from his first marriage, Henriette Rapp, also ended up in the US. She had married Siegmund Schwarz in Berlin on May 6, 1929, and they were living in Kirtof, Germany, in 1935.

Henriette Rapp marriage record to Siegmund Schwarz, Landesarchiv Berlin; Berlin, Deutschland; Personenstandsregister Heiratsregister; Laufendenummer: 189, 1929 (Erstregister)

Ancestry.com. Berlin, Germany, Marriages, 1874-1936

They immigrated to the US in 1937 and in June 1938 when Henriette, now using Rita, filed her declaration of intention to become a US citizen, they were living in San Francisco.

National Archives at Riverside; Riverside, California; NAI Number: 594890; Record Group Title: 21; Record Group Number: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009

Description: Petitions, 1943 (Box 0247), Ancestry.com. California, Federal Naturalization Records, 1843-1999

On the 1940 census, Rita and Siegmund, now going by Henry, were living in Los Angeles, and Henry reported no occupation, but Rita reported that she was a dressmaker.1 When Henry filed his World War II draft registration in 1942, he was still living in Los Angeles, but listed Alfred Kahn, not Rita, as the person who would always know where he was, so perhaps they were no longer together.2 Rita did remarry on April 14, 1956, in Los Angeles, to Max Altura.3

Arthur Rapp died in New York on January 10, 1951, at the age of 66.4 He was survived by his wife Alice and his three children, Rita, Harold, and Gordon. Alice survived him by 26 years; she died in May 1977 at 82 years old.5

Rita died in Los Angeles on June 10, 2003; she was 94. According to her obituary in the June 13, 2003 The Los Angeles Times, Rita was a “life member and generous benefactor of Hadassah, Rita was devoted to Israel and the Jewish people.”6

Arthur Rapp’s two sons also lived long lives. Harold Rapp, who had started his career as a watchmaker, became the president of Bulova International in Basel, Switzerland, for many years and was 93 when he died on February 11, 2016.7

His brother Gordon died the following year at 92. According to his obituary, he graduated from Cornell University and received a master’s degree from Purdue University. His early interest in agriculture stayed with him. He had a career in poulty genetics before spending twenty years as a product and marketing manager with Corn Products Corporation . His obituary described him as follows: “He was known for his kindness, creativity, humor, wisdom, and talent as a prolific artist, photographer and writer. He was a Renaissance man of many interests, including tennis, tai chi and chess. He enjoyed museums and classical music concerts in New York City and later in Chapel Hill, NC.”8

I was struck by the fact that Harold and Gordon both continued to work in the same fields where they had started as young men, Harold in watches, Gordon in agriculture. Harold Rapp and Gordon Rapp were survived by their widows, children, and grandchildren.

Although Arthur Rapp did not have the blessing of a life as long as those of his three children, he was blessed with the good fortune of escaping with them from Nazi Germany and thus giving them the security and safety to live those long lives, during which they each made important contributions to their new homeland and left a legacy of their accomplishments and future generations to carry on the Rapp name.

- Rita and Henry Schwarz, 1940 US census, Census Place: Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California; Roll: m-t0627-00403; Page: 10B; Enumeration District: 60-828, Ancestry.com. 1940 United States Federal Census ↩

-

Henry Schwarz, World War II draft registration, The National Archives in St. Louis, Missouri; St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards for California, 10/16/1940-03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147; Box: 1619,

Ancestry.com. U.S. WWII Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947 ↩ -

Rita H Rapp, Estimated birth year: abt 1909, Age: 47, Marriage Date: 14 Apr 1956

Marriage Place: Los Angeles, California, USA, Spouse: Max D Altura, Spouse Age: 55

Ancestry.com. California, Marriage Index, 1949-1959 ↩ -

Arthur Rapp, Age: 66, Birth Date: abt 1885, Death Date: 10 Jan 1951

Death Place: Queens, New York, New York, USA, Certificate Number: 481

Ancestry.com. New York, New York, Death Index, 1949-1965 ↩ -

Alice Rapp, Social Security Number: 105-36-2290, Birth Date: 24 Feb 1895

Issue Year: 1962, Issue State: New York, Last Residence: 10028, New York, New York, New York, USA, Death Date: May 1977, Social Security Administration; Washington D.C., USA; Social Security Death Index, Master File, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014 ↩ -

Rita H. Altura, Social Security Number: 555-16-5231, Birth Date: 21 Sep 1908

Issue Year: Before 1951, Issue State: California, Last Residence: 91335, Reseda, Los Angeles, California, USA, Death Date: 10 Jun 2003, Social Security Administration; Washington D.C., USA; Social Security Death Index, Master File, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014. Obituary can be seen at https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/latimes/obituary.aspx?n=rita-altura&pid=1083894 ↩ - I could not find Harold Rapp in the SSDI or any obituary, just this listing on FindAGrave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/159069023 However, I found numerous articles about his work at Bulova, and this wedding announcement for his son that mentions his career at Bulova. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/15/fashion/weddings/shelley-grubb-and-kenneth-rapp.html?searchResultPosition=2 ↩

- Gordon Rapp, The New York Times, December 26, 2017, found at https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/nytimes/obituary.aspx?n=gordon-d-rapp&pid=187633991 ↩