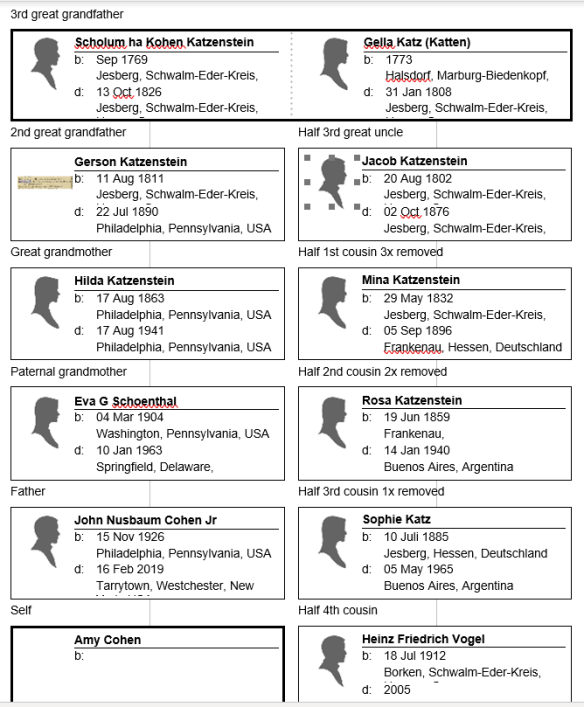

We saw that the family of Sarah Goldschmidt and Salomon Stern’s daughter Keile Stern Loewenthal experienced much growth and prosperity during the 1910s and 1920s. This post will focus on their two sons, Abraham and Mayer, and their lives between 1910 and 1930.

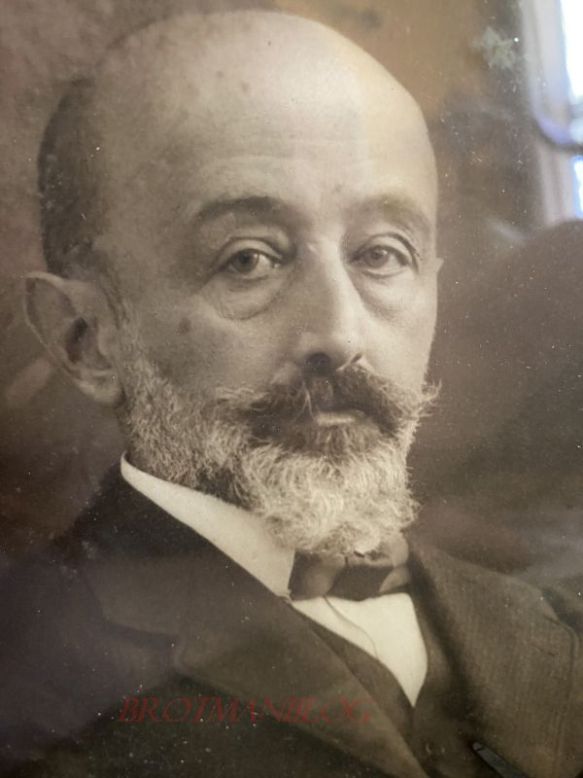

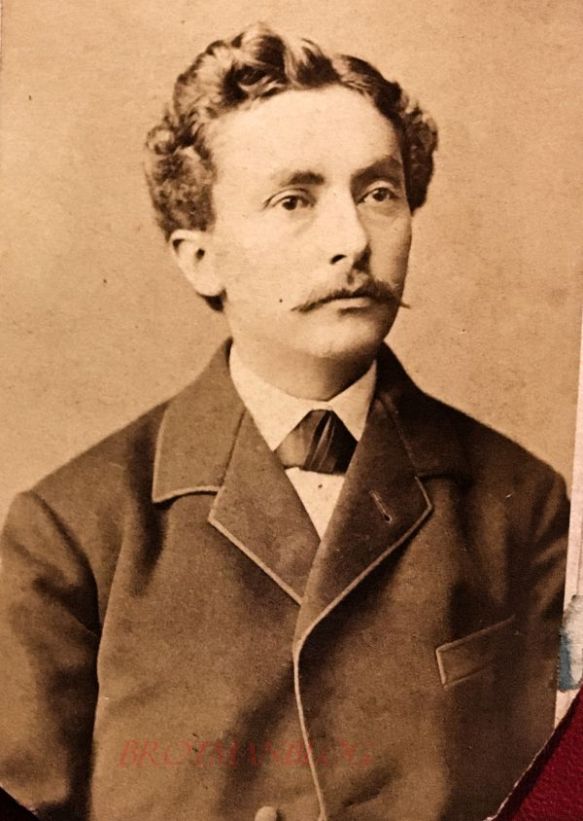

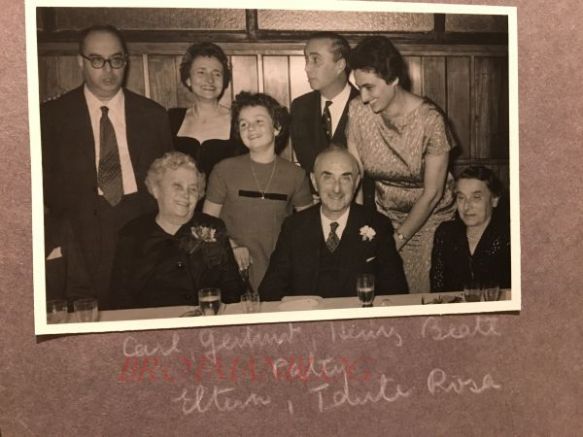

As of 1910, Abraham (known as Adolf) Stern and his wife and first cousin Johanna Goldschmidt had four grown children: Siegfried, Clementine, Sittah Sarah, and Alice. I am so grateful to Siegfried’s grandson Rafi Stern, my fifth cousin, who kindly shared the photographs that appear in this post.

This photograph shows the house where Abraham and Johanna lived and raised their children in Frankfurt. As you can see, the family was quite comfortably situated as Abraham was a successful merchant in Frankfurt.

Home of Abraham Adolf Stern and Johanna Goldschmidt in Frankfurt. Courtesy of their great-grandson, Rafi Stern.

Their son Siegfried Stern married Lea Hirsch on June 4, 1912, in Frankfurt.1 She was born in Halberstadt, Germany, on April 10, 1892, to Abraham Hirsch and Mathilde Kulp.2 Siegfried and Lea had two sons, Erich Ernst Benjamin Stern, born March 27, 1913, in Frankfurt,3 and Gunther Stern, born May 5, 1916, in Frankfurt.4

Abraham and Johanna’s second child Clementine Stern was married to Siegfried Oppenheimer, a doctor, and had a daughter Erika, born in 1909, as seen in my earlier post. Clementine would have two more children, William Erwin Oppenheimer, born on October 29, 1912, in Frankfurt,5 and Sarah Gabriele Oppenheimer, born July 20, 1917, in Frankfurt.6

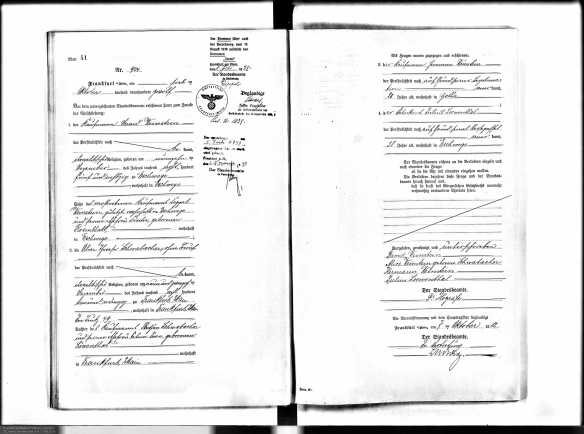

Clementine’s sister Sittah Sarah Stern married Abraham Albert Mainz on October 3, 1911, in Mainz. He was born in Paris, France, on May 31, 1883, to Leopold Mainz and Hermine Straus.

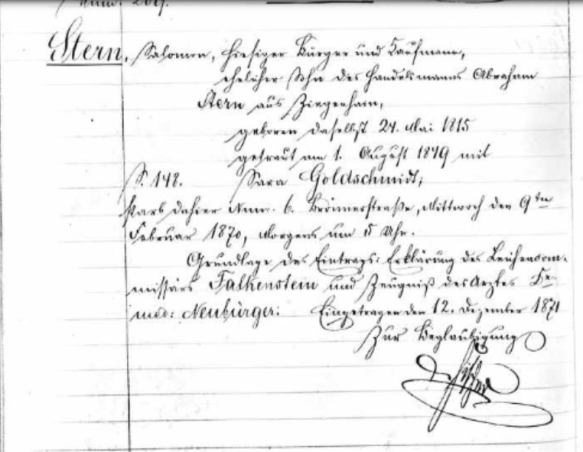

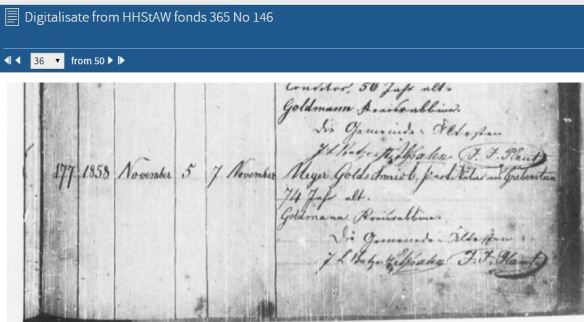

Marriage record of Sarah Sittah Stern and Abraham Mainz, Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Wiesbaden, Deutschland, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Marriages, 1849-1930

Sittah Sarah and Abraham Mainz would have two children, Marguerite Wera Mainz, born in Frankfurt on October 22, 1913,7 and Helmut Walter Solomon Mainz, born April 13, 1918, in Frankfurt.8 The photograph below depicts their home in Frankfurt on the first and second floors of the building.

Abraham and Johanna would lose their two oldest children in the next several years. First, Clementine Stern Oppenheimer died on January 18, 1919, in Frankfurt. She was only 29 years old and left behind three young children, Erika (ten), William Erwin (seven), and Sarah Gabriele (two). Like millions of others, Clementine died from the Spanish flu epidemic, according to her great-nephew, my cousin Rafi.

Clementine Stern Oppenheimer death record, Personenstandsregister Sterberegister; Bestand: 903; Signatur: 10812, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Deaths, 1851-1958

A year later, as so often happened in Jewish families back then, Clementine’s younger sister Alice Lea Stern married Clementine’s widower Siegfried Oppenheimer. They were married on October 6, 1920, in Frankfurt.

Marriage record of Alice Lea Stern to Siegfried Oppenheimer, Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Wiesbaden, Deutschland; Bestand: 903, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Marriages, 1849-1930

Alice and Siegfried would have five children together in the 1920s.

Just two years after losing Clementine, Abraham and Johanna lost their first born, Siegfried Stern. He died on July 9, 1921, in Oberursel, Germany. He was only 32. He died at the Frankfurter Kuranstalt Hohemark, a psychiatric hospital. According to his grandson Rafi, Siegfried had suffered a business failure and become despondent. He was hospitalized and tragically took his own life. He left behind his wife Lea and their two young children Erich (eight) and Gunther (five).

Siegfried Stern death record, Personenstandsregister Sterberegister; Bestand: 908; Signatur: 3821, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Deaths, 1851-1958

Below is Siegfried’s gravestone, one of the most beautiful I’ve ever seen, and the inscription is heartbreaking to read, knowing Siegfried’s story. I am grateful to the members of Tracing the Tribe for this partial translation:

Here lies buried Mr. Shlomo son in Mr. Asher Avraham STERN “shlita” (indicates that his father was alive at the time of the sons death).

A man who feared G-d, he revived the hearts of the downtrodden in secret.He was pure in his thoughts and pure in his body, and all his purpose was the returning of his soul, pure, to his maker.

He respected his father and his mother with all of his ability.

He respected his wife more than his own body.

He died with a good name at the age of 32 to the sorrow of all that knew him, on the holy day of Shabbos, 3 Tamuz, and was buried with crying and eulogies on Monday the 5th of the same month. (5)681 (according to the small count) (1921).

May his soul be bound in the bonds of life.

Siegfried’s widow Lea remarried a few years after Siegfried’s death and would have two more children with her second husband, Ernst Sigmund Schwarzschhild.9

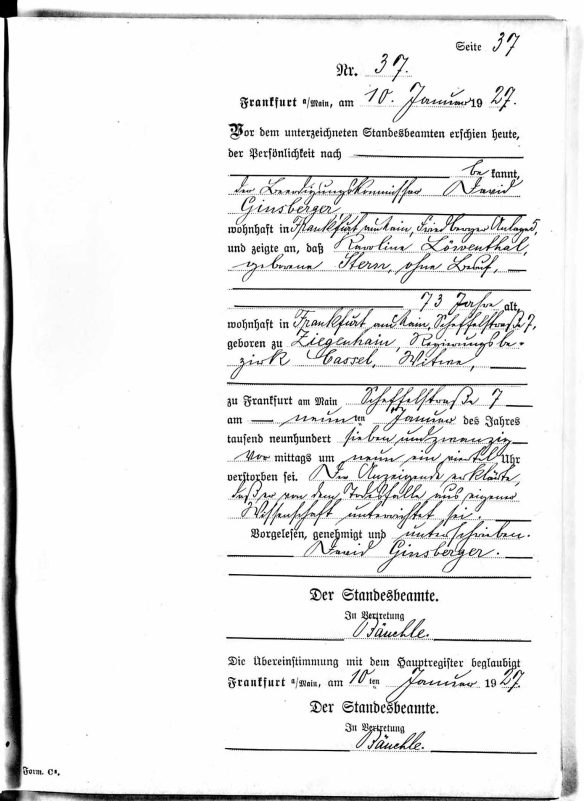

Not long after losing his children Siegfried and Clementine, Abraham Adolf Stern himself passed away. He died on December 29, 1925, at the age of 67. He was survived by his wife/cousin Johanna and his two remaining children, Sittah Sarah and Alice Lea, and his grandchildren.

Abraham Stern death record, Personenstandsregister Sterberegister; Bestand: 903; Signatur: 10909, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Deaths, 1851-1958

The kind people at Tracing the Tribe translated Abraham’s gravestone for me:

Here is buried

Asher Avraham son of Shlomo called Adolf Albert Stern

a great man and a leader of his people

complete in his deeds and of good discernment.

The beginning of his wisdom comes from his belief in GodHe oversaw his children and descendants

His house was a house of the righteous and a dwelling place of Torah

His soul is entwined in that of his humble wife.

You are gone and caused the middle of the day to turn dark. From heaven you are alive with us.Died 12 Tevet and buried 14th of the month, [year] 5686 / [abbreviation]

May his soul be bound in the bond of life.

Abraham’s brother Mayer Stern and his wife Gella Hirsch had two children born in the 1890s, Elsa and Markus. Elsa married Jacob Alfred Schwarzschild on January 22, 1911, in Frankfurt. Jacob was the son of Alfred Isaac Schwarzchild and Recha Goldschmidt and was born February 12, 1885 in Frankfurt. Jacob was Elsa’s second cousin. His mother Recha was the daughter of Selig Goldschmidt, and Elsa’s father Mayer was the son of Sarah Goldschmidt, Selig’s older sister. Once again, the family tree was bending around itself.

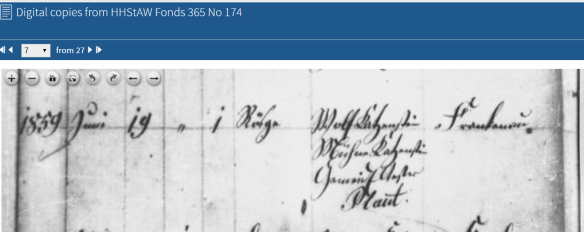

Marriage record of Elsa Stern and Jacob Schwarzschild, Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Wiesbaden, Deutschland, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Marriages, 1849-1930

Elsa and Jacob had one child, Elizabeth, reportedly born July 26, 1915, in Frankfurt.10

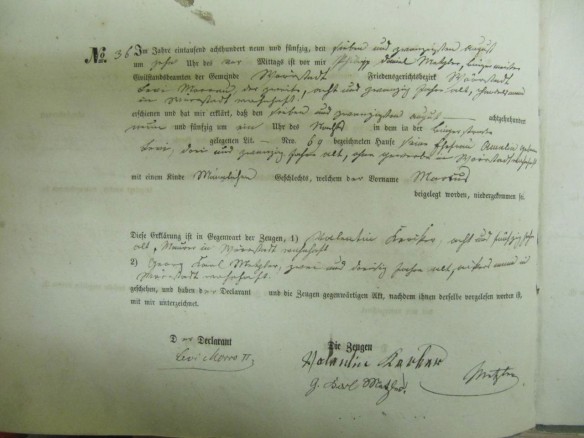

Elsa’s marriage to Jacob did not last, despite the cousin relationship. The marginal comment on their marriage record attests to their divorce. Thank you to the members of the German Genealogy group who provided the translation of this comment:

Certified transcript

By decree nisi of the Regional Court at Frankfurt on Main, which became final at the end of 27 June 1920, the marriage between the banker Jakob Alfred Schwarzschild and Else Sara Schwarzschild née Stern has been divorced.

Frankfurt on Main, 13 October 1920

Civil Registry Clerk

pp. Dippel

Certified

Frankfurt on Main, 9 February 1921

[Signature]

Court Clerk

On August 18, 1920, just months after the divorce became final, Elsa Stern Schwarzschild married Alfred Hirsch. Alfred was born in Hamburg to Esaias Hirsch and Charlotte Wolf on May 19, 1890. Together, Alfred and Elsa had three children born in the 1920s.11

Marriage record of Elsa Stern to Alfred Hirsch, Year Range and Volume: 1920 Band 03

Ancestry.com. Hamburg, Germany, Marriages, 1874-1920

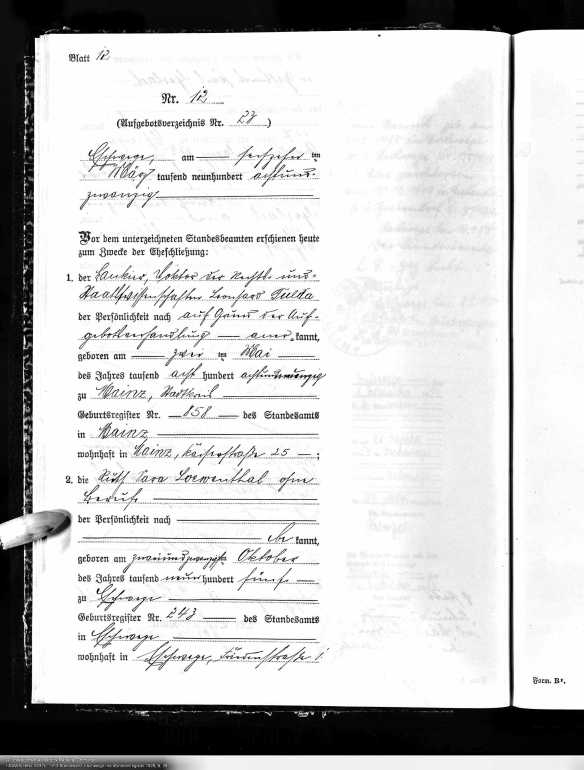

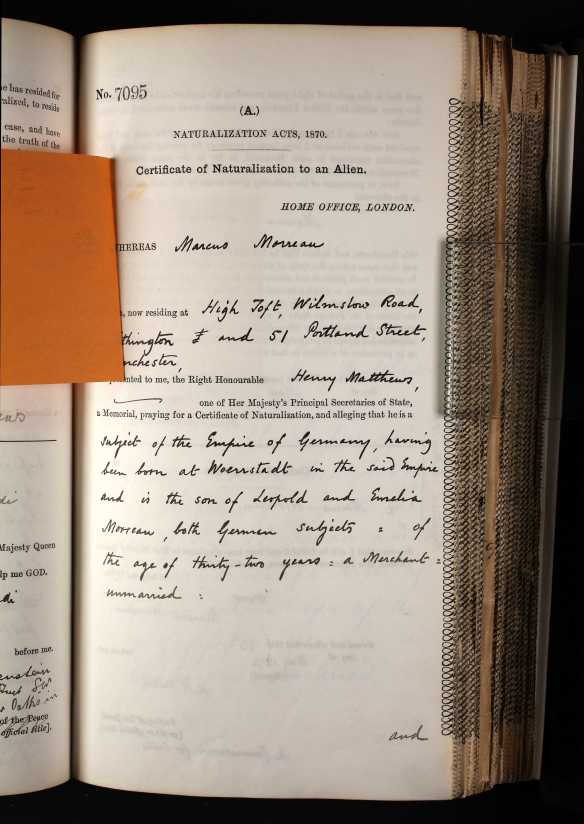

Mayer and Gella’s son Markus married Rhee (Rosa) Mess on August 25, 1923, in Frankfurt. She was born in Radziwillow, Poland on July 25, 1898, to Samuel Mess and Ester-Raza Landis.12

Thus, as the family approached the 1930s, Sarah Goldschmidt’s surviving descendants were living comfortable lives, but had suffered a number of terrible losses between 1910 and 1930, including two of Sarah’s children, Keile and Abraham, and three of her grandchildren, Abraham’s children Clementine Stern Oppenheimer and Siegfried Stern, and Keile’s daughter Martha Loewenthal Wolff.

But Lina and Mayer were still living as of 1930 as were eight of Sarah’s grandchildren. All of them would see their comfortable and prosperous lives as German Jews upturned by the rise of Nazism in the coming decade.

- The marriage date comes from the Cibella/Baron research; I have no primary source for this specific date, but it is clear that Siegfried and Lea married before 1913 when their son Erich was born. ↩

- Certificate Number: 98, Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Wiesbaden, Deutschland; Bestand: 903, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Marriages, 1849-1930. ↩

- The National Archives; Kew, London, England; HO 396 WW2 Internees (Aliens) Index Cards 1939-1947; Reference Number: HO 396/89, Ancestry.com. UK, WWII Alien Internees, 1939-1945 ↩

- The National Archives; Kew, London, England; HO 396 WW2 Internees (Aliens) Index Cards 1939-1947; Reference Number: HO 396/197, Ancestry.com. UK, WWII Alien Internees, 1939-1945 ↩

- Application for Palestinian Citizenship, Israel State Archives website found at https://www.archives.gov.il/en/archives/#/Archive/0b07170680034dc1/File/0b071706810638e5 ↩

- SSN: 121546243, Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007 ↩

-

The National Archives; Kew, London, England; HO 396 WW2 Internees (Aliens) Index Cards 1939-1947; Reference Number: HO 396/222, Description

Piece Number Description: 222: Dead Index (Wives of Germans etc) 1941-1947: Eastw-Fey, Ancestry.com. UK, WWII Alien Internees, 1939-1945 ↩ - The National Archives; Kew, London, England; HO 396 WW2 Internees (Aliens) Index Cards 1939-1947; Reference Number: HO 396/58, Ancestry.com. UK, WWII Alien Internees, 1939-1945 ↩

- Marriage record of Ernst Schwarzschild and Lea Hirsch Stern, Certificate Number: 98, Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv; Wiesbaden, Deutschland; Bestand: 903, Ancestry.com. Hesse, Germany, Marriages, 1849-1930 ↩

- This is the date provided by Cibella/Baron. I also found one record for an Isabel Schwarzschild Weil born on that date: The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; NAI Number: 2848504; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787 – 2004; Record Group Number: 85; Series Number: A3998; NARA Roll Number: 701, Ancestry.com. New York State, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1917-1967. I believe this is for Elsa and Jacob’s daughter. I am still looking for additional records. ↩

- Application for Palestinian Citizenship, Israeli State Archives, at https://www.archives.gov.il/en/archives/#/Archive/0b07170680034dc1/File/0b07170680fd6abf ↩

-

National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, DC; NAI Title: Index to Petitions for Naturalizations Filed in Federal, State, and Local Courts in New York City, 1792-1906; NAI Number: 5700802; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: RG 21, Description

Description: (Roll 1256) Petition No· 352904 – Petition No· 353350, Ancestry.com. New York, State and Federal Naturalization Records, 1794-1943 ↩