When Selig Goldschmidt died on January 13, 1896, he was survived by his six children and eighteen grandchildren. In his will, he had wished them happiness and love and hoped they would live good lives, following the faith and practices of Judaism and giving back to their communities.

For the first thirty years of the twentieth century, his hopes for his children were largely fulfilled. Then everything changed. In the next series of posts I will look at each of the children of Selig and Clementine (Fuld) Goldschmidt and their lives in the 20th century, starting with their oldest child, Helene Goldschmidt Tedesco.

As we saw, Helene Goldschmidt, the oldest child of Selig Goldschmidt and Clementine Fuld, married Leon Tedesco on June 9, 1876, in Frankfurt. I was very fortunate to find and connect with Helene’s great-great-grandson Lionel, and he has generously shared with me many wonderful photographs as well as the story of his family including information about his 3x-great-grandfather, Leon’s father, Giacomo (Jacob) Tedesco.

Leon’s father Giacomo Tedesco was born in Venice, Italy, on August 27, 1799, and in 1833 he married Therese Cerf, a Parisian, and started a small art supplies store in Paris. Giacomo provided art supplies to artists in exchange for some of their art work. From that collection, he created what grew to be the famous and extremely successful Tedesco Freres gallery. Giacomo was also a very committed Jew who helped build a modern mikvah in Paris, contributed to the development of a synagogue, founded the first kosher butcher shop in Paris, and served as a mohel.

After Giacomo died in 1870, his sons Leon and Arthur took over the business of the gallery. Leon became a close friend of the artist Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, the famous French landscape painter and printmaker who was considered “the leading painter of the Barbizon school of France in the mid-nineteenth century.” The National Gallery in Washington, DC, has several works that came from the Tedesco Freres collection, including this work of Corot:

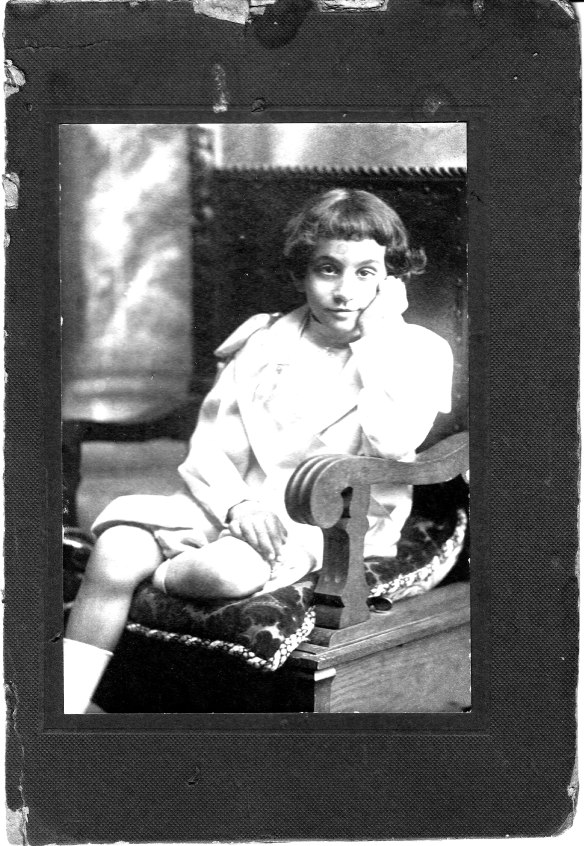

Helene and Leon’s son Giacomo was born in Paris on July 28, 1879, and was obviously named for his recently deceased grandfather. Giacomo, the grandson, married Henriette Lang on February 9, 1901, in Paris; she was the daughter of Louis Lang and Louise Blum and was born in Paris on January 31, 1882.1 Giacomo worked with his family in the art gallery. He and Henriette had two daughters, Irene, born December 23, 1902, and Odette, born July 16, 1907.2

Here is an absolutely gorgeous photograph of young Odette with her mother Henriette:

This wonderful photograph is of Leon Tedesco, his granddaughter Odette, her mother Henriette Lang Tedesco, and her grandmother, Helene Goldschmidt Tedesco.

Front: Leon Tedesco, Odette Tedesco, Helene Goldschmidt Tedesco. Rear: Henriette Lang Tedesco. Courtesy of the family

Helene and Leon’s son Giacomo served in the French armed forces during World War I. It must have been strange to be on the opposite side of the war from his Goldschmidt family living in Frankfurt.

Odette married Mathieu Charles Weil on October 24, 1929. Mathieu was born in Strasbourg, France, on August 21, 1894, to Isidore Weil and Jeanne Levy.3 Lionel shared this beautiful photograph from their wedding day:

Leon Tedesco died on August 7, 1932, at the age of 79.4 Lionel described his great-great-grandfather as “a strong and handsome man who looked like the King of Belgium.” This photograph of Leon with Helene certainly reflects Lionel’s description:

Leon was survived by his wife Helene, his son Giacomo, his two granddaughters and his great-granddaughter. All of them then had to face the Nazi era.

According to Lionel, the Tedesco family left Paris after the invasion of France by the Nazis in 1940. The family lost everything they had—which was substantial as Leon Tedesco’s art business had been extremely successful. Not only did they lose the business, they also lost most of the valuable art and antiques they’d owned.

Helene Goldschmidt Tedesco died in Marseille, France, on August 21, 1942; she was 84 years old. Her granddaughter Irene Tedesco died on November 12, 1942, in Oberhoffen, France, in the Alsace region. Lionel had no information regarding Irene’s cause of death, except to say that she had apparently had some health challenges since birth.5

The rest of the family survived the Holocaust and the war years by being safely hidden. Nadine, Lionel’s mother, still remembers that between the age of 9 and 14, after fleeing from Paris, she lived and went to school in many locations in southern France: Annet, Bordeaux, Arcachon, Salles, Sariac, Cassis, Marseille, Grenoble, Villars de Lans, and Autran. Most of the time she lived with her parents and her grandmother Henriette. Her grandfather Giacomo was hiding elsewhere in France. During the war, Nadine used two different names to hide her identity as a Jewish girl: Nicole Varnier and Mady Mercier.

Mathieu Weil joined the resistance movement and is depicted in this photograph with others who were fighting against the Nazis:

At one point the family was hiding in the Vercors region with a woman named Charlotte Bayle, who had known the Tedesco family for six generations. When Mathieu Weil, Odette’s husband, was very ill with typhoid, the Gestapo came to Charlotte’s door looking for him. Charlotte lied and said he had left three days ago when in fact he was lying in bed in the next room. The whole family left immediately. Lionel credits Charlotte Bayle with saving the lives of his mother, grandparents, and great-grandmother. Here is a photograph of Charlotte Bayle with Odette Tedesco Weil:

After the war the family returned to Paris and began to rebuild their lives. Giacomo Tedesco died in Paris on June 29, 1950; he was seventy years old. Giacomo’s wife Henriette Lang Tedesco died on March 3, 1961, in Paris.6

Although Lionel did not know his great-grandparents Giacomo and Henriette, he knew his grandmother Odette very well. He described her as a very fine and elegant woman. He also said that although the family had been very religious before the war, their level of observance faded in the aftermath of the war. But their commitment to Judaism always remained strong and central to their lives. Odette died on July 16, 1987;7 she was predeceased by her husband Mathieu Weil on August 20, 1972.8 Both died in Paris.

Thank you so much to my fifth cousin Lionel and his mother Nadine for sharing these wonderful photographs and the story of his family.

-

Giacomo Jacob Tedesco, Marriage Bann Date: 9 févr. 1902 (9 Feb 1902)

Father’s Name: Léon Tedesco, Mother’s Name: Hélène Goldschmidt, Spouse’s Name: Henriette Lang, Ancestry.com. Paris, France & Vicinity Marriage Banns, 1860-1902 ↩ - Odette Tedesco, Gender: femme (Female), Death Age: 80, Birth Date: 16 juil. 1907 (16 Jul 1907), Birth Place: Paris-16e-Arrondissement, Paris, Death Date: 16 juil. 1987 (16 Jul 1987), Death Place: Paris-16E-Arrondissement, Paris, France, Certificate Number: 1005, Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques (Insee); Paris, France; Fichier des personnes décédées; Roll #: deces-1987.txt, Ancestry.com. Web: France, Death Records, 1970-2018. Irene’s birth date came from the work of David Baron and Roger Cibella. ↩

-

Mathieu Charles Weil, Gender: homme (Male), Death Age: 77, Birth Date: 21 août 1894 (21 Aug 1894), Birth Place: Strasbourg, Bas-Rhin, Death Date: 20 août 1972 (20 Aug 1972), Death Place: Paris-16E-Arrondissement, Paris, France

Certificate Number: 1230, Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques (Insee); Paris, France; Fichier des personnes décédées; Roll #: deces-1972.txt, Ancestry.com. Web: France, Death Records, 1970-2018 ↩ -

Name: Leon Tedesco, Death Date: 7 Aug 1932, Death Place: Paris, France

Probate Date: 8 Jun 1933, Probate Registry: London, England, Ancestry.com. England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1995 ↩ - These dates come from the work of David Baron and Roger Cibella and are also seen on the Geni profiles for Helene and Irene. ↩

- These dates come from Baron and Cibella and also from Geni. ↩

- Odette Tedesco, Gender: femme (Female), Death Age: 80, Birth Date: 16 juil. 1907 (16 Jul 1907), Birth Place: Paris-16e-Arrondissement, Paris, Death Date: 16 juil. 1987 (16 Jul 1987), Death Place: Paris-16E-Arrondissement, Paris, France, Certificate Number: 1005, Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques (Insee); Paris, France; Fichier des personnes décédées; Roll #: deces-1987.txt, Ancestry.com. Web: France, Death Records, 1970-2018 ↩

-

Mathieu Charles Weil, Gender: homme (Male), Death Age: 77, Birth Date: 21 août 1894 (21 Aug 1894), Birth Place: Strasbourg, Bas-Rhin, Death Date: 20 août 1972 (20 Aug 1972), Death Place: Paris-16E-Arrondissement, Paris, France

Certificate Number: 1230, Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques (Insee); Paris, France; Fichier des personnes décédées; Roll #: deces-1972.txt, Ancestry.com. Web: France, Death Records, 1970-2018 ↩